All There Is to Know, More or Less

Encyclopedic Understanding. An A-to-Z Review of Simon Garfield’s ‘All the Knowledge in the World’

Alphabetical arrangement is an odd way to communicate information about the world. Why, for instance, should aardvark take precedence over atom, agriculture, astronomy, algebra, or autonomy—all of which seem more significant than a small nocturnal mammal?

Beyond that, an alphabetical arrangement severs the natural, logical relationship between elements. “Would such a random process not be considered absurd in any other constructive situation in life,” asks Simon Garfield, “such as the placement of skilled workers on a production line ordered to work next to the person closest alphabetically in surname, irrespective of their role?”

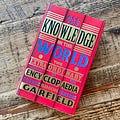

Could it even work? Seems silly to ask now. The cultural success of the encyclopedia—a set of books with the aim of wrangling all necessary knowledge into a manageable, accessible package—makes alphabetical arrangement seem obvious, even inevitable in retrospect. Garfield’s book, All the Knowledge in the World, charts the winding path of that success from the encyclopedia’s speculative origins to its digital apotheosis of the form in Wikipedia.

Despite this hindsight view, however, alphabetical organization was far from obvious in the beginning. In 1817, almost fifty years after the final volume of Encyclopedia Britannica first emerged, poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge complained that alphabetical sorting hadn’t organized knowledge; it had fractured it. The project was marked by “more or less complete disorganization,” all the thematic, systematic, historical, scientific, and philosophical bonds between subjects being yanked apart and their disconnected elements dropped into predetermined abecedarian slots. But then Coleridge only complained because he cared. Many did.

Existing models for the modern encyclopedia dot the ancient and medieval timeline. Scholars had long wrestled with the need to corral civilization’s growing body of information into something approachable, comprehensible. Garfield mentions, for instance, Pliny’s Natural History, Isidore of Seville’s Etymologies, and the Byzantine Suda.

For their part, Isidore and his disciple Braulio arranged the Etymologies, their “grand tour of civilization,” in logical sections starting with grammar, rhetoric, math, medicine, and law, moving through the Bible, theology, human anatomy, animals, elements, and more, ending with wars, manufacturing, and food. Sensible enough. Coleridge would approve. And all of that could squeeze into twenty books—though not for long.

Gutenberg’s innovations with print and moveable type exacerbated the knowledge challenge. While Isidore’s Etymologies busied scribes in the manuscript era—nearly a thousand copies still exist—it also flourished in the print era. No wonder. People’s appetite for information, both to produce and consume it, proved insatiable. Print exploded the number of books in circulation. From the sixth to the fifteenth centuries, European scribes produced nearly 11 million books by hand. But in just 150 years of print, between 1452 and 1600 printers produced some 212 million—an increase of 1,846 percent in a fraction of the time.

How could people keep up? Racing presses pressed the question. By 1680 Gottfried Leibniz lamented a “horrible mass of books which keeps on growing,” worrying “disorder will become nearly insurmountable.” There was too much to know and too many books to read to learn it all.

Instead of abandoning readers to the wilds of this uncontainable, metastasizing “mass of books,” enterprising writers, editors, and publishers realized they could epitomize, condense, and compile like Pliny and Isidore and, while doing so, possibly correct errors and update understanding. Print posed the problem, and print presented the solution.

Juggling all that knowledge, however, seemed to necessitate the compromise of alphabetical organization. Coleridge advocated something different. His Encyclopaedia Metropolitana, says Garfield, “emphasized the systematic relationships within knowledge bases, presenting the sciences, the arts and other subjects as a rational and unified progression rather than scattered constellation.” The project’s thirty-nine volumes, issued between 1817 and 1845, were exhaustive—and exhausting. Difficult to use, Metropolitana’s top-down, idealized organization flopped.

Knowledge possesses a quality its more aggressive fans sometimes forget: A little goes a long way for most people. The ability to dip in and out of a set of books for a choice fact or tidbit is all that’s usually necessary. What’s a cumulus cloud? Who was Charlemagne? No one wants to undertake an inductive exploration of the entire world to understand how coins are minted or what happened at Waterloo. The alphabet, paired with brief explanatory articles, offered the perfect means to find a serviceable amount of information. A century before Coleridge most encyclopedists had reconciled themselves to the compromise. By the time the Encyclopaedia Britannica first emerged in 1768, significant cultural momentum drove the adoption of the method.

Libraries with thousands of volumes could find themselves affordably reduced to a single shelf. The “professed design” of the Britannica, according to its founding editor Williams Smellie, was to “diffuse the knowledge of science” through radical abridgment.

“Many writers,” said Smellie, “have acquired the dexterity of spreading a few critical thoughts over several hundred pages. . . . When an author hits upon a thought that pleases him, he is apt to dwell upon it. . . . Though this may be pleasant to the writer, it tries and vexes the reader.”

Norms emerged from this commitment to concision, and alphabetical arrangement didn’t disorganize information as Coleridge had claimed; rather, it allowed readers to organize it for themselves on the fly as they needed it—bottom-up, rather than top-down. With expectations shaped by these norms, the market began to fill with other providers doing largely the same thing but with their particular editorial twist on the scheme: A-to-Z presentation of whatever specialists, students, or the average lay readers might require. Britannica was joined by Encyclopedia Americana, Collier’s, Funk & Wagnalls, World Book, and others. The goal for each? To be both comprehensive and comprehensible.

Outdated information undercut the goal from the start. If encyclopedias were first meant to keep people up to date as the world advanced, what would keep the encyclopedias up to date as knowledge did the same? Industrialization, globalization, and later digitization set an impossible pace. Updated editions might be decades apart and annual supplemental volumes could only patch up so many holes.

Paul Otlet had a wild idea: What if you unbound the encyclopedia? With Coleridge undoubtedly corkscrewing in his grave, across the English Channel in Belgium at the turn of the twentieth century Otlet imagined deconstructing knowledge down to its barest bits and pieces. More than imagine it, he did it, building an analog database with millions of fact cards filed alphabetically in wooden drawers—“like Google, but on paper,” as Garfield says.1

Quixotic is one way to describe Otlet’s idea. But he recognized the limitations of the traditional encyclopedia, especially as new forms of communication circulated more information than ever before. Otlet’s almost exact contemporary, H. G. Wells, also recognized limitations in the era’s information infrastructure. Wells proposed a World Encyclopedia “in continual correspondence with every university, every research institution, every competent discussion, every survey, every statistical bureau in the world.” Neither Otlet nor Wells’s solutions would prove workable, but each had envisioned facets of the Internet; technology would eventually catch up.

Return to Coleridge’s complaint, that alphabetical organization was really disorganization. Otlet and Wells wrestled with similar difficulty. The sheer amount of information in the world defied attempts to organize it, and top-down solutions could only go so far. They all devised ultimately unsatisfactory solutions. What they failed to factor? The user of the information might require a greater say in how it was organized.

Sales tactics showed what encyclopedia thought of their customers. Garfield documents tricks and gimmicks used to rook buyers into buying expensive sets, including outright lies. As time went on, a homeowner might sooner allow a burglar into the house than an encyclopedia salesman, as Monty Python turned into an amusing sketch. Culturally, the encyclopedia was at an impasse. It had evolved to the outer limits of its own usefulness and commercial desirability.

Technology offered the way out. When I was young, my maternal grandfather had a massive cream-colored set of encyclopedias; whenever I raised a question he directed me to look up the answer. At home we had a smaller, blue clothbound set; I recall using it to write a paper on World War I in middle school. But something new arrived early in my college days: Microsoft’s multimedia CD-ROM encyclopedia, Encarta.

Updating information was now a cinch. Beginning life as a refreshed version of Funk & Wagnalls, Encarta maintained a content and design team to keep its knowledge base current. Customers needed to purchase new discs early on, but later the service allowed live updating. Best of all, users had multiple ways to navigate the material, using both top-down subject hierarchies and bottom-up hyperlinks and search.2

Volumes have been written—and more could be and will be—about the Internet’s impact on information generation, organization, and dissemination. For our purposes here, let’s limit ourselves to one observation: It simultaneously killed the last vestige of encyclopedia culture and enabled the next stage of its evolution, best exemplified by Jimmy Wales’s Plan B.

Wikipedia was an afterthought. Wales wanted to create a digital encyclopedia, Nupedia, featuring peer-reviewed expert articles. But the production timeline was excruciatingly slow. Wales and his team experimented with wiki software to speed up production, allowing nonexperts to contribute. But wouldn’t lay contributors sully the Nupedia brand? They decided to launch Wikipedia separately—and good thing, too. It rocketed past Nupedia went on to become one of the biggest sites on the Internet. Nupedia was quietly abandoned.

Xanadu was Coleridge’s name for Kubla Kahn’s paradisiacal palace, a singular center of earthly delights. For infovores Wikimedia almost lives up to the designation. “Since its creation in January 2001,” says Garfield, “Wikipedia has grown into the world's largest online reference work, attracting more than 500 million page views per day and 1 billion unique visitors each month. . . . It offers a total of more than 54 million articles in about 270 languages, including . . . 6,390,565 articles in English that have been subject to 1,044,294,099 edits since 2001 (with 19.21 edits per page). That makes it 93.11 times the size of Encyclopaedia Britannica, and the equivalent of 2979.7 Britannica volumes.” Those stats were true as of October 9, 2021. I just checked: It’s now up to 6,694,480 articles in English.

Younger readers will marvel we ever consulted a shelf of physical books for the kind of information we now turn to Wikipedia for, let alone waited a year or more for updated information. But it was the path that got us to now. Coleridge might still lament the utter fragmentation of knowledge, but the bottom-up arrangement of Wikipedia—of the whole Internet—is the only way to organize so much data. Inquirers have to direct their own inquiries. Alphabetical organization on paper was, for its time, a significant step toward that reality.

Zoom out and the history of the encyclopedia presents a fascinating chapter of the human project, our grappling with the infinitude of knowledge and the finitude of our minds. Zoom in and the nooks and crannies of the story provides delightful characters, difficult concerns, and brain-wracking challenges, some of which we’re still wrestling with today. If you’re going to zoom in, Simon Garfield’s All the Knowledge in the World makes the ideal guide and companion for the journey.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related posts:

My first exposure to Paul Otlet’s story was from

’s delightful essay in , “Let There Be More Biographies of Failures.” I happened to be reading Garfield at nearly the same time, followed by Simon Winchester’s Knowing What We Know, which also details Otlet’s project.If you’ve never seen Encarta—or haven’t seen it in a few decades—here’s a tour. And here’s a conversation with members of the design and development teams; it’s remarkable how forward-thinking and resourceful they were.

Are you familiar with Adler's Synopticon project? It was an attempt to arrange knowledge by themes instead of alphabetically. A failed attempt but fascinating.