Accursed Questions: Why Russian Lit Matters

Andrew D. Kaufman on Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, the Women Behind Their Success, More

I knew once I read and reviewed Andrew D. Kaufman’s biography of Dostoevsky’s wife, Anna Dostoevskaya, I wanted to talk with him. The urge only amplified as I discovered more about Kaufman and his work.

Not only is Kaufman the author of The Gambler Wife: A True Story of Love, Risk, and the Woman Who Saved Dostoyevsky (a finalist for the 2022 PEN/Jacqueline Bograd Weld Award for “biography of exceptional literary, narrative, and artistic merit, based on scrupulous research”), he’s also the author Give War and Peace a Chance: Tolstoyan Wisdom for Troubled Times; Understanding Tolstoy; and Russian for Dummies.

Kaufman holds a doctorate in Slavic Languages and Literatures from Stanford and until 2022 served as associate professor and assistant director of the Center for Teaching Excellence at the University of Virginia. While at the University of Virginia, he created the popular Books Behind Bars program, documented in the movie Seats at the Table, that convenes both college students and correctional-facility inmates to discuss Russian literature.

The program and Kaufman’s work more broadly has been featured in the Washington Post, New York Times, PBS, NPR, Oprah.com, The Today Show, Moscow Times, and Russian national television. He’s also spoken at TEDx, the Aspen Institute, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Russian Academy of Sciences, and other prestigious venues.

Here we discuss the relevance of Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, and other nineteenth-century Russian writers to our lives in the modern world.

What originally drew you to Russian literature and what keeps it fresh for you?

What has always drawn me to Russian literature is the way the great writers and their characters grapple in a deep and personal way with what the Russians call the “accursed questions”: Who am I? Why am here? How should I live? I’ve been something of a seeker myself and have found solace and wisdom in these books whose stories continually remind me that I’m on this planet for a short time and so living fully and truthfully is imperative.

Tolstoy said it well when he wrote that “the goal of an artist is not to solve problems, but to force people to love life in all its countless, inexhaustible manifestations.” The same is true of readers, too, and approaching Russian literature from this perspective is what has kept it fresh for me.

How can something as particular as nineteenth-century Russian literature also feel so universal?

To tell one human story well is to tell the story of our shared human experience. I recently taught Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment to a group of inmates. It’s the story of a poverty-stricken, twenty-one-year-old student who commits a double murder and then spends the rest of the novel unraveling why he did what he did. But by telling the specific story of one nineteenth-century man’s tortuous journey from crime to redemption, Dostoevsky managed to tell a universal story we all can relate to.

The inmates in my class ranged in age from twenty-five to seventy, and only one of them was in for murder like the novel’s protagonist. Yet they all resonated powerfully with Dostoevsky’s description of how social environment, family background, unhealed trauma, and flawed thinking can lead a person to make the worst and most consequential decision of their life.

“To tell one human story well is to tell the story of our shared human experience . . . Literature can help us find the beauty in the broken, see light in the darkness, and even experience joy in the midst of hardship.”

—Andrew D. Kaufman

Through my conversation about the novel with the inmates, I discovered just how much Crime and Punishment relates to my life, as well. I, too, have made terrible decisions, like the time I set the neighbor’s woods on fire at the age of eight. My attraction to the dangerous thrill of pyromania overpowered whatever rational analysis of my decision my eight-year-old brain may have been capable of.

Turns out, I, like the inmates, was a living embodiment of one of Dostoevsky’s key insights in Crime and Punishment: human behavior cannot be explained by reason alone.

You’ve spoken publicly about experiencing significant suffering. I’m thinking primarily about the loss of your father and your hip replacement. You’ve also spoken about the palliative power of literature. How does literature enable us to cope amid our pain?

Literature can help us find the beauty in the broken, see light in the darkness, and even experience joy in the midst of hardship. Many of the Russian writers I’ve studied suffered greatly. Dostoevsky was sentenced to mock execution for his participation in a revolutionary society before being exiled to a Siberian labor camp for four years. Solzhenitsyn spent eight years in a Soviet work camp. Karolina Pavlova, a great nineteenth-century woman writer, was silenced by the male-dominated literary establishment and died forgotten, only to be discovered a half century after her death.

What all these writers have in common is that they never lost their faith in human promise. That takes a rare sort of courage that we find in some of the best and wisest writers. Anybody can be hopeful when things are easy. What about when things fall apart, as they so often do? That’s when we need the wisdom and inspiration of great writers who have lived through hell and still believed in human possibility.

“What all these writers have in common is that they never lost their faith in human promise.”

—Andrew D. Kaufman

What does it mean for teachers to, as you’ve said, “stop thinking of themselves as purveyors of expert knowledge and start to play the role of facilitators of human learning and personal growth for their students.” Can you describe that in action?

My field of expertise is Russian literature, but I use the literature as a vehicle for a kind of learning that goes well beyond the literary. I don’t care if, in ten years, my students remember the names of the characters in War and Peace or how Dostoevsky employs the technique of polyphony to capture reality in his novels. What I do care about is whether they’ve changed as human beings as a result of our time together, whether they’ve gained some new insight about the value of struggle, how to bear witness to the difficult stories of others, how to live well and wisely in troubled times.

All of these are recurrent themes in Russian literature. I love getting emails from students three, five, and ten years after they took my class, like one in which a student wrote: “Your class made me feel so alive. Russian literature taught me to keep reaching for the stars while keeping my feet on the ground and appreciating the beauty of the everyday.”

Given the decline in reading in primary and secondary education, how can we ensure that the current generation of students are suitably equipped for cultural engagement? How should parents and teachers respond to the challenge?

I believe in the importance of literacy and a literary education as one of the building blocks of cultural engagement and rejuvenation. My own Books Behind Bars program has been my attempt at reigniting students’ love of literature and using literature to build bridges of empathy. But our current cultural crisis has deeper spiritual roots that won’t necessarily be solved through a focus on reading. It will be solved when we take a hard, honest look as teachers and parents at the habits of mind and heart we’re modeling for our children in our classrooms and all aspects of our lives.

Are we relating authentically and listening compassionately to one another? Can we hear opinions that we passionately disagree without resorting to stonewalling, invective, or violence? Are we willing to make space in our hearts for the outcast, the orphan, or the inmate who has made terrible mistakes in their life? Do we choose love, even when it is hard?

These are the capacities that will be essential to restoring our broken democracy and our humanity. We can certainly cultivate these through reading, but something more is needed: a commitment to a different way of relating and living. I’ve shared what this might look like in a classroom setting in this article.

“Are we relating authentically and listening compassionately to one another? Can we hear opinions that we passionately disagree without resorting to stonewalling, invective, or violence?”

—Andrew D. Kaufman

What led you to create Books Behind Bars and how do you continue that work today?

Books Behind Bars is a class that brings together university students and incarcerated students to explore questions of meaning, value, and social justice though conversations about Russian literature. This class, which I created in 2010, is an extension of my lifelong passion to help make literature personally meaningful to wide audiences.

The immediate inspiration for the class was a workshop I led in 2009 on Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich at the Virginia Beach Correctional Center. As the incarcerated men and I grappled in a deeply personal way with the key question raised by the novella—given that I’m going to die, how should I live?—I realized that this was the sort of alive classroom I’d been seeking to create for years: one where conversations about Russian literature quickly became urgent conversations about real life.

Moved by what I experienced in the workshop, I wanted to created a college class that brought together two very different groups of student and see what could happen. Books Behind Bars, then, started off as an educational experiment and became my life’s works for over a decade. The course has motivated students on both sides to rethink their lives, relationships, and careers.

I left the University of Virginia in 2022 but have continued this work in different forms. I recently taught Crime and Punishment to incarcerated men and also to prosecutors. One of the prosecutors in the class was so moved by Dostoevsky’s message of compassion that he changed his office mission statement to “Safety and stability through healing and repair.”

He’s the commonwealth attorney of the city of Charlottesville, and this change will affect the way he and the attorneys who report to him prosecute moving forward. Tens of thousands of lives will be affected. It is a wonderful example of the power of literary education to affect real social change.

What’s one lesson you’ve learned from residents of correctional facilities that has changed the way you look at the world?

I have learned that we are all broken in one way or another. We have all made mistakes. We all suffer from some form of unhealed trauma. The moment we separate ourselves from others by distancing ourselves from them or judging them is the moment we forget that are on the same human journey. As Dostoevsky said through a character in The Brothers Karamazov, “Everything like an ocean flows and comes into contact. You touch in one place and at the other end of the world it reverberates.”

“The moment we separate ourselves from others by distancing ourselves from them or judging them is the moment we forget that are on the same human journey.”

—Andrew D. Kaufman

What drew you to Anna Dostoevskaya’s story?

I knew Anna was important to Dostoevsky’s life from the biographies of him I’d read. It wasn’t until I started digging into her memoirs, letters, and other unpublished materials that I understood just how important she was. She was everything to Dostoevsky, both personally and professionally.

Without Anna’s business acumen, courage, and love, Dostoevsky likely never would have written The Idiot, The Possessed, or The Brothers Karamazov, depriving the world of culture-shaping masterpieces. Anna saved him and his career in every sense and bequeathed to the world a great gift.

She was extraordinarily accomplished in her own right. As Russia’s first solo female publisher, she earned her family $5 million in today’s money. She was the founder of Russia’s first literary museum, Dostoevsky’s first bibliographer, a tireless supporter of charities and founder and funder of the first school for peasant girls. That school, by the time of its closing, had graduated a thousand girls who otherwise never would have had access to an education.

Despite these accomplishments, there had not been a single biography of Anna in English before my book and only two in Russian. I was determined to fill this lacuna and restore Anna to her rightful place in literary history.

After I reviewed The Gambler Wife, several people wrote to tell me that Tolstoy had a similar arrangement with his wife. What can you tell us about that situation?

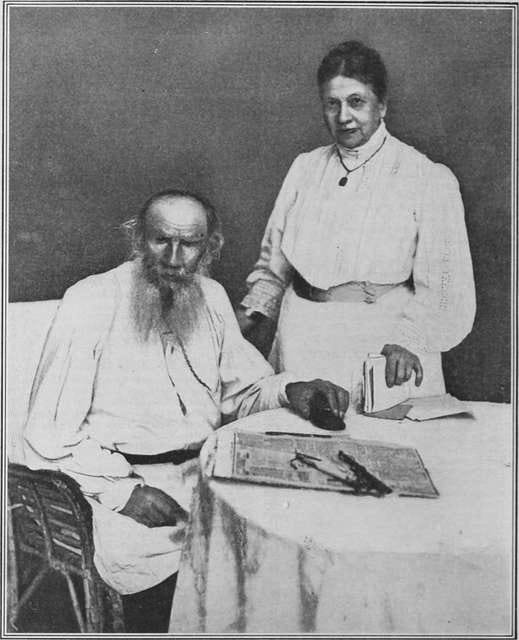

There were indeed similarities. Like Anna Dostoevskaya, Sofya Tolstaya actively managed her husband’s literary career while overseeing the home and navigating his emotional volatility. The connections run deeper still: Sofya had heard about Anna’s success as a publisher of Dostoevsky’s works, and came to ask Anna for her advice on how to create a publishing operation for her husband similar to the one Anna had created for hers.

Without a hint of competitiveness, Anna shared her secrets of the trade, and she was deeply satisfied when her counsel helped Countess Tolstaya found a highly profitable publishing imprint of her own. These are some of the obvious parallels between the two marriages.

But there was one major difference: The Dostoevsky partnership worked, providing Anna with deep emotional satisfaction and professional fulfillment. The Tolstoy marriage, by contrast, was marked by constant resentment, envy, and misunderstanding on both sides.

That marriage ended with Tolstoy secretly leaving his wife of fifty years in the middle of night. Tolstoy left her with a note thanking her for their years together but asking her to not follow him and allow him die alone in peace. Dostoevsky, by contrast, frequently expressed his profound love and gratitude for Anna, telling her in one letter that “you are the only woman who ever understood me.”

“The Dostoevsky partnership worked, providing Anna with deep emotional satisfaction and professional fulfillment. The Tolstoy marriage, by contrast, was marked by constant resentment, envy, and misunderstanding on both sides.”

—Andrew D. Kaufman

Dostoevsky and Tolstoy are often compared and contrasted. How do their differences reflect their personal philosophies and approaches to life?

Tolstoy’s novels depict the norms and continuities of human behavior by means of grand narratives that expand slowly over time and against the backdrop of vast natural tableaus. “As is usually the case” and “such as often occurs” are phrases you encounter frequently in Tolstoy.

Dostoevsky’s world, by contrast, is one in which you can come home one evening and “suddenly” find an axe buried in your skull. Life is always on the verge of imploding on itself. Tragedy is just around the corner, or in your living room. He shows the dangerous allure of abstract ideas as well as the psychological crises, cracks, and explosions of the soul that have become familiar in our modern world.

The biography of these two contemporaries partly explains their different visions of life. Dostoevsky was a man of the city. He felt its vigorous pulse but also its pain. He had trouble making ends meet. Yoked to a ruinous gambling addiction, he was constantly in debt and struggled to meet publisher’s deadlines. His writing often feels frenzied, because life often felt to him as it were teetering on the edge of the abyss. Contributing to this sensibility was Dostoevsky’s experience of being two minutes away from execution by firing squad.

Tolstoy, by contrast, lived on a sprawling, thousand-acre estate at Yasnaya Polyana. He was surrounded by a large family and protected by an entourage of servants. His cocoon-like environment allowed him to tune out whatever aspects of the contemporary world he found unsavory and instead meditate on and often idealize the distant past. Because he was financially independent, he could write slowly, over long periods of time, taking extended breaks to hunt, tend his beehives, and enjoy his growing family.

It is revealing that in the same years (the mid 1860s) that Dostoevsky was penning Crime and Punishment, a book about a harried, confused city kid who commits a double murder, Tolstoy was writing War and Peace, an historical epic about Russian heroism during the Napoleonic wars of five decades earlier.

Both men were deeply religious, but I tend to think of Dostoevsky as a traditionalist and Tolstoy as something of an innovator. How does that show up in their work?

Religiously and politically, Dostoevsky was definitely more conservative than Tolstoy. Though in his youth he was sentenced to mock execution for revolutionary activity, Dostoevsky later became a foremost apologist of the Russian autocracy and defender of Christian Orthodoxy. Tolstoy, by contrast, was always a rebel, vehemently criticizing the government and the Church, for which he was eventually excommunicated.

The contrast is evident when you compare Dostoevsky’s last novel, The Brothers Karamazov, with Tolstoy’s last, Resurrection. Brothers is a book about a parricide. Dostoevsky’s contemporary readers would have understood the novel as a thinly veiled metaphor for the frequent attempts on the Tsar-Father’s life that had become a hallmark in the increasingly radicalized Russian society in the second half of the nineteenth century. Dostoevsky believed that only a return to the Christian Orthodox principles embodied in Alyosha Karamazov would save Russia from disaster.

In Resurrection, Tolstoy offers a bitterly scathing critique of both the autocracy and the Russian Orthodox Church, which he believed perverted the core message of Jesus as expressed in The Gospels. The moral bankruptcy of the Church becomes for the writer a microcosm of everything that is corrupt and inhumane about late nineteenth-century Russia.

Resurrection was the final straw that got Tolstoy excommunicated. To my knowledge, the Russian Orthodox Church to this day has refused to reinstate the writer or acknowledge him as a good Christian. (This is the same Church that vehemently supports Putin and his genocidal war in Ukraine. But that’s a conversation for another time.)

“Religiously and politically, Dostoevsky was definitely more conservative than Tolstoy . . . Tolstoy, by contrast, was always a rebel. . . .”

—Andrew D. Kaufman

Most of us know the big names, but who’s one underrated Russian novelist you wish more people knew about?

I’d like more readers to know about some of the lesser known but important Russian women writers, like the extremely talented Karolina Pavlova, who died in obscurity, only to be rediscovered a half century after her death. When she started to make a name for herself in the 1840s, male critics and editors mercilessly lampooned her for choosing a literary career over a domestic life of pickling and jelly-making.

Pavlova’s 1848 novel, A Double Life, is the only major work she managed to publish in her lifetime. The largely autobiographical work is about a young woman trapped in a stifling aristocratic culture that demands she be lovely, sweet, and virtuous, whereas at night she escapes to the world of dreams, where she makes contact with an essential, lost part of her identity.

I’d also like to encourage readers to explore Nadezhda Mandelshtam’s Hope Against Hope (1970), one of the great twentieth-century memoirs about life at the height of Stalinism. If you’re interested in poetry, I would also recommend two of twentieth-century Russia’s supreme poets, Marina Tsvetaeva and Anna Akhmatova, whose visionary works depict what it felt like for a woman to live and love at that dark time.

Final question: You can invite any three authors for a lengthy meal. Neither time period nor language is an obstacle. Who do you pick, why, and how does the conversation go?

I’d like to play relationship counselor for this one and invite Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, and Turgenev, the three greatest nineteenth-century Russian novelists who were competitive and had rocky relationships with one another.

Tolstoy and Turgenev knew each other in their youth but had a falling out that ended with Turgenev challenging Tolstoy to a duel and their not speaking for years.

Dostoevsky, for his part, was envious of the more urbane and wealthier Turgenev. Their relationship, too, ended with a falling out after an acrimonious meeting in which the two writers traded personal insults. They didn’t speak for years.

Dostoevsky was envious of Tolstoy’s wealth and success, and Tolstoy was often critical of Dostoevsky’s harried prose and tortured plots. Though they happened to be in the same room attending the same lecture in 1880, Tolstoy reportedly refused an introduction to Dostoevsky through a mutual acquaintance in attendance.

It’s time to bring these three men together to break bread and put their rocky pasts behind them. I’d start off the evening by bringing them up to date on twentieth and twenty-first-century history, and say: “Okay, guys, so as you see, humanity is in crisis. We need you to help us figure out where we all go from here. Let’s cut the childish antics and get down to serious work!”

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

I want to thank you for your Substack Joel. The writing is so good. thoughtful, balanced, inspires me to think. Truly an island of excellence in a sea of subterfuge.

Thanks for this Joel! Andrew's work and writing has been such an inspiration.