Reading ‘War and Peace’ in Both War and Peace

How Leo Tolstoy’s Classic Novel Travels Across the Many Seasons of Life

Summer before last I started reading Leo Tolstoy’s 1867 classic War and Peace aloud to my husband and our older children, aged eleven and sixteen. This year, just as spring was shading into summer again, we finished it.

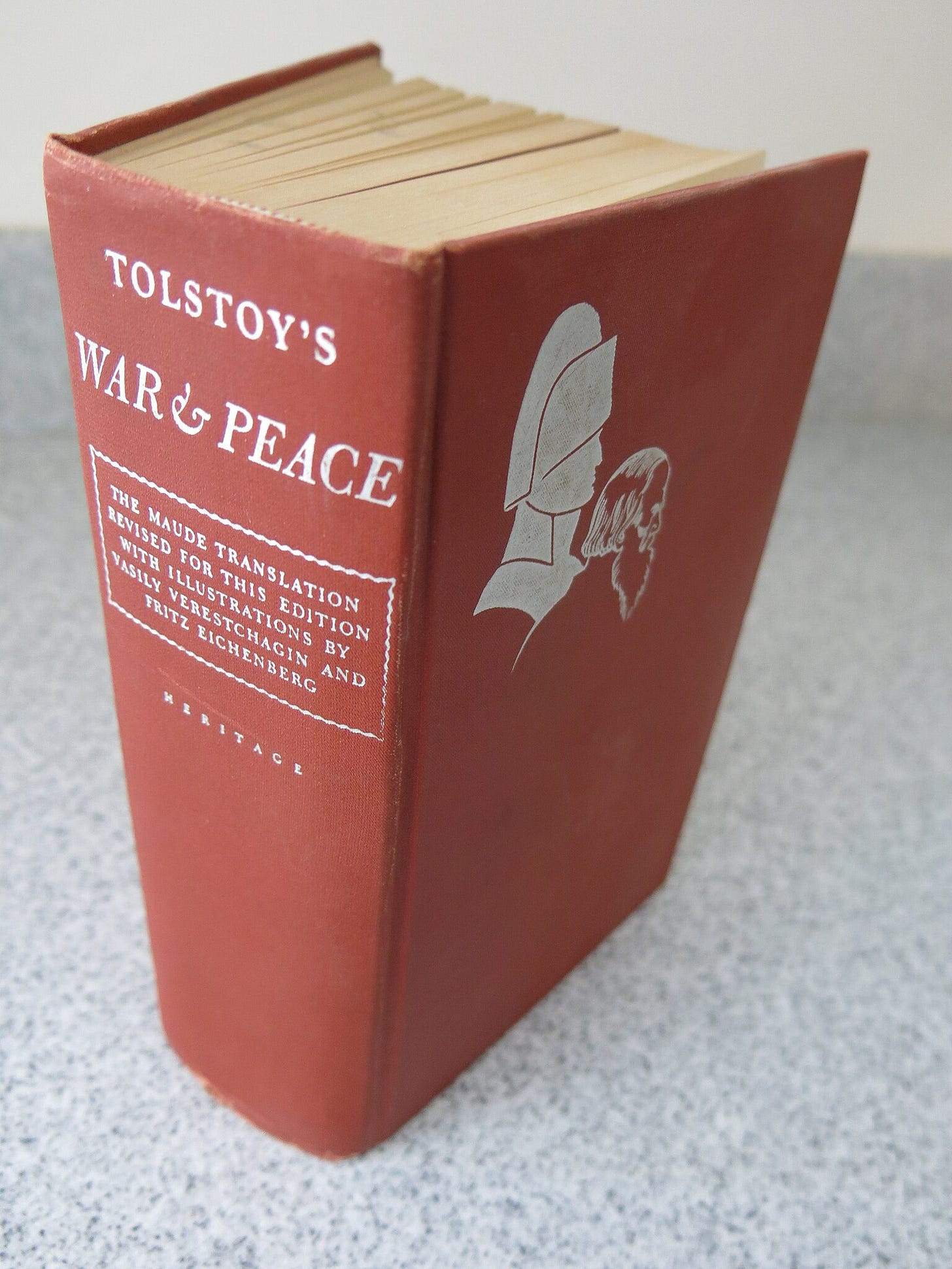

It didn’t really take a full two years to read—we took last summer off to work our way through Shakespeare’s Roman plays. And we only read on evenings everyone was home, averaging three or four days each week. But still. At around 575,000 English words and 1,200 pages depending on the translation and edition, Tolstoy’s famous historical novel is . . . long.

You might not know it from the way War and Peace functions in pop culture, but it’s not the longest novel out there. Atlas Shrugged and Les Misérables are similarly long, to pick just two. Proust’s In Search of Lost Time is twice the length and then some.

But War and Peace has become a cultural referent in a way other big books have not. Looney Tunes, the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and the Simpsons have all riffed off War and Peace. Charles Schulz used it for decades to make Charlie Brown’s life more difficult. Even Garfield, America’s favorite orange cat, reads War and Peace as part of a gag about how long it’s taking to upload a computer file.

Reading in Peacetime

I had read War and Peace before, silently to myself, and enjoyed it. But when my husband asked for it as a family read-aloud, I balked. Reading aloud is slow. Reading aloud reveals the weak spots in written language, which can make the wrong book a real misery for the reader. And eleven-year-olds were not necessarily Tolstoy’s target audience.

I had visions of wading eternally through heavy text with a grudging audience. But it was important to my husband to share this book he loves with his children, and the kids were willing to give it a try. I had seen Constance Garnett’s 1904 translation billed as the most readable. So I bought a used copy, and we dug in.

Maybe part of the reason this book lives in our cultural consciousness as the epitome of long is the title. War and Peace is about as all-embracing as Douglas Adams’s Life, The Universe, and Everything, or Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time. And it was appropriately chosen. War and Peace follows dozens of characters over a period of fifteen years—before, during, and after Russia’s involvement in the Napoleonic wars—and reaches beyond its timeline with references to previous events and hints of things still to come.

Over the course of the story, children and young adults grow to maturity, take jobs, fall in love and out again, get married. Women and men who have been supporting households, military units, whole villages, pass into old age and find their sphere of influence drawing in. People die of childbirth, of illness, of wounds, of old age, of grief. Babies are born and nursed and bathed. Political powers wax and wane. Sunrise, sunset.

I needn’t have worried about whether the book was a good choice as a read-aloud. By the time we got to the policeman and the bear, the kids were hooked. And while there were sometimes places where Tolstoy’s repetition pulled me out of the story and back to the mechanics of a passage, for the most part it was smooth sailing.

We read in sweatshirts and bare feet around the firepit in the long summer evenings with subtle notes of birdsong and woodsmoke weaving into the story. We read under blankets snuggled on the couch by the wood stove in the winter, keeping company with the crackle of the fire and the steady drumming of rain on the roof. We squeezed in short sections on nights when dinner ran long, and read as long as my voice would hold out on quiet Sunday afternoons.

Along the way, we worried about characters and rolled our eyes over their foibles. We wanted to shake some of them until their teeth rattled. We laughed out loud. We argued with Tolstoy, and then with each other, over his views on historiography. We stopped to discuss cultural background and expectations, how different the past was and how familiar. We looked things up online. We talked about family history. We talked about what love looks like and what it means to be brave.

The eleven-year-old and sixteen-year-old became a thirteen-year-old and an eighteen-year-old; I moved from my thirties to my forties.

Reading in Wartime

When I first read War and Peace, I read late at night, alone, hunched over a little e-reader in a pool of yellow light in the dark house. I was a young mother, with young kids. My husband was gearing up for another deployment, and a kind friend had given him the e-reader to take with him. When he wasn’t using it, I read as many as I could of the public domain classics that came with it, among them Louise and Aylmer Maude’s 1922 translation of War and Peace.

It was a strange thing, reading about home fronts and battlefields two hundred years in the past, while closely engaged with a homefront and a second-hand war of my own.

I wasn’t far removed from the kind of fumbling steps into young adulthood that several main characters were taking. Separated from my husband by an invisible wall of war-zone experiences, I devoured the parts of the book that might give me insight into that part of his life. Tolstoy was a combat veteran, and it seemed as if being shot at must have similarities whether the weapons used were muskets and cannons or AK-47s and mortars.

Now our war is history, a fact that was brought home to me when a child interviewed me about it for a school assignment this year. The first of our children is entering adulthood, older now than his father was when he joined the Army.

Changing Reader, Changing Book

Whole portions of War and Peace that I didn’t even remember from my first reading stood out to me as I read it aloud: the way different stages of one person’s life can seem as if they happened to different people, the changing relationships between aging parents and adult children in the prime of life, the fragility of peace.

Certainly there are themes that I noticed in each reading. Tolstoy examines what makes a good life, how to reconcile the material and the spiritual, how little, little control we humans really have. But in a very real sense, reading the book at two such different times in my own life was like reading two different books.

This, I think, is what makes War and Peace a classic.

For as much as we joke about the book’s length, it has such depth and texture that it comes alive for readers of widely differing experiences, at widely differing points in life. I hope that I will have time in my own life to read it a third time in another fifteen years or so. I’d like to see what Russian-American husband-and-wife translators Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhosnsky make of the text.

And I want to see what kind of a book it will be—what kind of a person I will be—a little farther down the road.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Before you go, compare

’s reading plan with what’s driving down literacy in the U.S.:And combine it with John Stamps’s lively review of Dostoevsky’s classic:

After several attempts at War and Peace (as a student of Napoleonic history) I only cracked it enough to finish after I started studying Russian language and finally got the patronymics and could follow the characters. Later on a guided tour of Napoleon’s occupation of Moscow (more Tolstoy than history) I swear I could hear the French guns and limbers trundling through Arbatsky Ploschad heading for the Kremlin.

Thank you! I’m not someone who tends to reread books. My stack of “want to read” unread books just keeps growing larger and my time to read shorter! But you’re making me reconsider at least this one. And, how I would have loved to be part of that lush family experience next to the fire or on those cozy blankets! No one in your family will ever forget that. Wonderful!