Read Along: Hidden Story Arcs (Matt. 16—Mark 9)

Reading the Gospels Together: Come Share What You’re Seeing as We Go

The gospels are stories. Do we realize that as we read? We’re reading the gospels all the way through in the month of September, and there are some notable benefits that come from that kind of focused attention.

“I am noticing how different it feels to read this story as a whole, rather than the small sections that we normally read in worship services,” shared reader Sara Schott in last week’s Read Along post. “Even though those are often ‘in order,’” she said, “there is a sweep to the story that we don’t get with the small sections.”

I think that’s exactly right. The Gospel of Matthew presents a single, unified story, but we tend to think of it as a bundle of anecdotes—a grab bag of vignettes. We forget that all the episodes roll up into an overarching narrative arranged by Matthew for a particular purpose and effect.

Shake, Rattle, and Roll

A simple example: At the start of Matthew (2.3) Herod and the people of Jerusalem are “troubled” by the Magi’s natal pronouncement about the king of the Jews. Then, when Jesus enters Jerusalem three decades later, riding a donkey in a symbolic claim of kingship (see Zechariah 9.9 and 1 Kings 1.33–34), the people are again rattled.

Some translations make this clearer than others, but as it says in the New Revised Standard Version, “the whole city was in turmoil” (21.10). Translator Sarah Ruden goes hyper literal when she offers “the whole city was shaken” since the underlying Greek refers to the movement of an earthquake.

Another parallel deployed by Matthew juxtaposes the earlier Beatitudes with a later litany of Woes. The Sermon on the Mount starts with a string of “blessed are theses and thoses” (5.3–12), but once Jesus enters Jerusalem he fires a series of judgments at the scribes and Pharisees (23.13–36).

In both instances, Matthew arranges these scenes in parallel. The second scene echoes the first—that is, the rumor and now the reality of Jesus’s arrival startles and unsettles the people; and while the pure in heart are blessed, the hypocritical scribes and Pharisees are anything but.

The gospels are not a blank reporting of facts. They are literary products, artfully constructed and meant to convey a whole host of impressions—much of which we might miss if we lose sight of the narrative “forest” of the story by fixating on the “trees” of individual anecdotes and episodes.

The Big Picture

The fixation on the trees happens for a variety of reasons, not least the way the texts themselves are displayed on the page. Chapter-and-versing tends to atomize the book. Just as bad, some Bibles insert passage headers every few paragraphs to guide the reader; the unintended effect is to actually stunt the awareness that each of these smaller bits contributes to a larger literary framework.

While the New English Bible (1961) does a terrible job of translating Matthew 21.10 (“the whole city went wild”), obscuring the parallel to 2.3, it does an excellent job of laying out the text as a literary product with narrative units meant to direct the reader along the path. How so? While retaining the traditional chapter and verses (though shoving them into the margins), it divides and displays the text in larger narrative units, which accentuates the book’s dramatic flow.

Here’s the outline the NEB editors broke it down:

The Coming of Christ (1.1–4.25)

The Sermon on the Mount (5.1–7.29)

Teaching and Healing (8.1–11.30)

Controversy (12.1–15.20)

Jesus and His Disciples (15.21–20.16)

Challenge to Jerusalem (20.17–23.39)

Prophecies and Warnings (24.1–25.46)

The Final Conflict (26.1–28.20)

These divisions frankly make much more sense to me than the chapters medieval editors gave us. What’s more, the longer units enable readers to settle into the narrative and get the flow of the story without tossing our attention up and down on arbitrary speed bumps.

You’ll notice that some of these modern passage breaks don’t align with stops and starts assumed by the medieval editors. Who’s right? Both and neither work just as well for answers because the question is mostly meaningless. But it also seems true that something approaching what the NEB editors were attempting to do respects the narrative nature of the book more than the work of the medieval editors.

It also explains why we sometimes struggle to understand the narrative flow of the gospels or get the sweep of the story when we’re just reading or hearing it in snippets and snatches. We’re breaking off before the action is fully resolved and thus miss its significance or how it contributes to the larger story.

Possible Arcs

Once you settle into reading Matthew as Matthew, taking the book in larger draughts and gulps, the narrative arc of the story emerges. Not coincidentally, the division of Matthew in the ESV Reader’s Gospels published by Crossway tracks almost exactly with the NEB outline, though it’s composed of nine sections, not eight. There are several possible ways to divvy it up, but there is an underlying logic—a narrative direction—that comes to the fore if we don’t tamp it down with arbitrary textual divisions or catch-as-catch can reading habits.

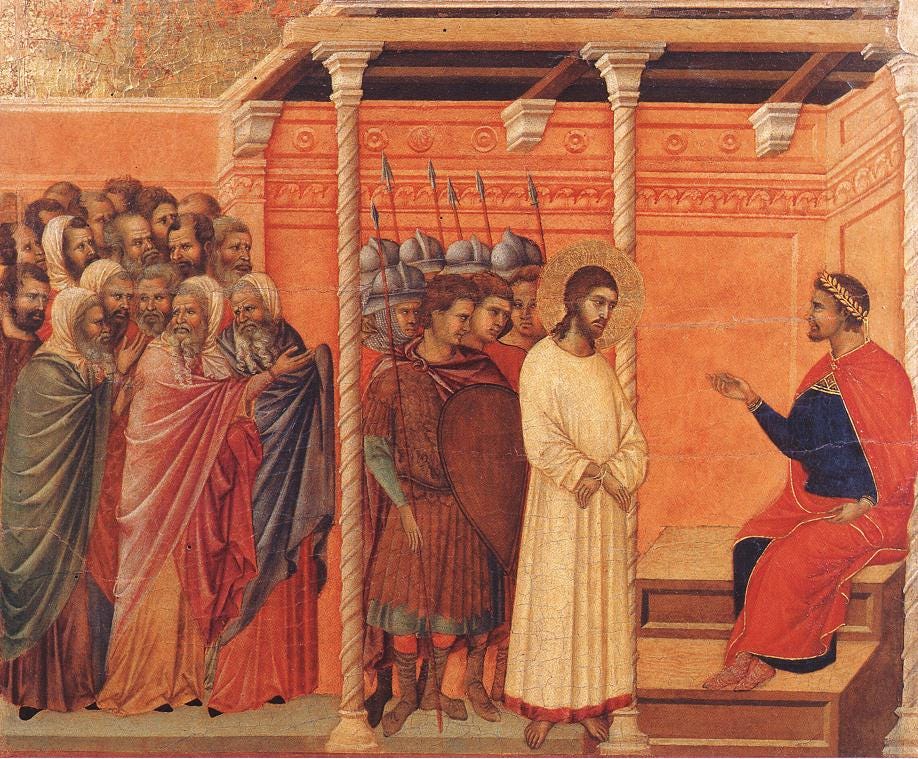

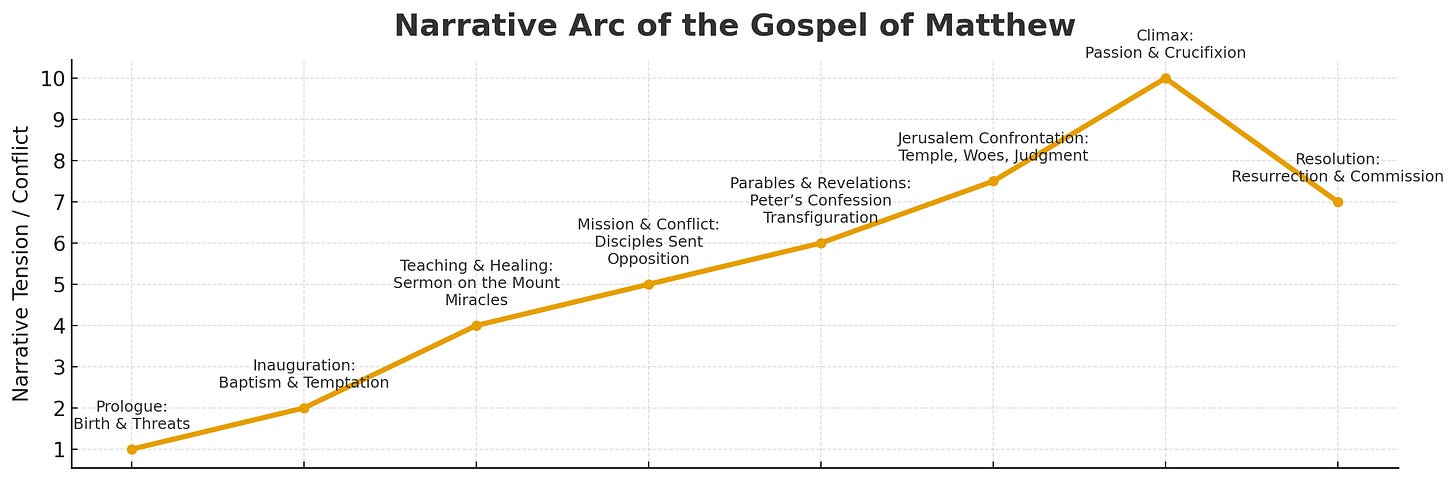

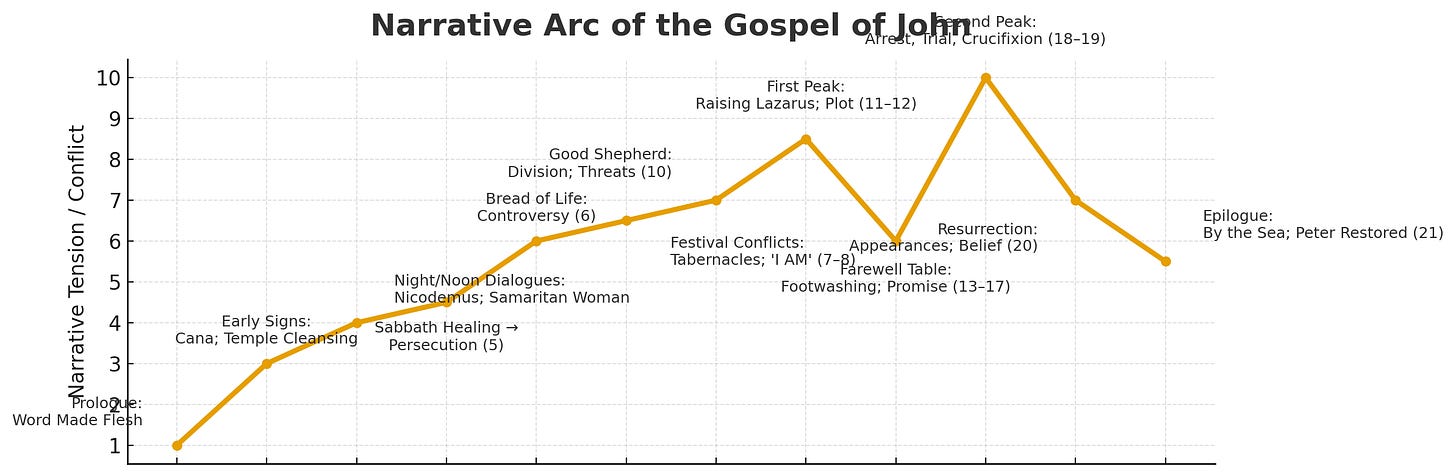

We can even visualize it, like so:

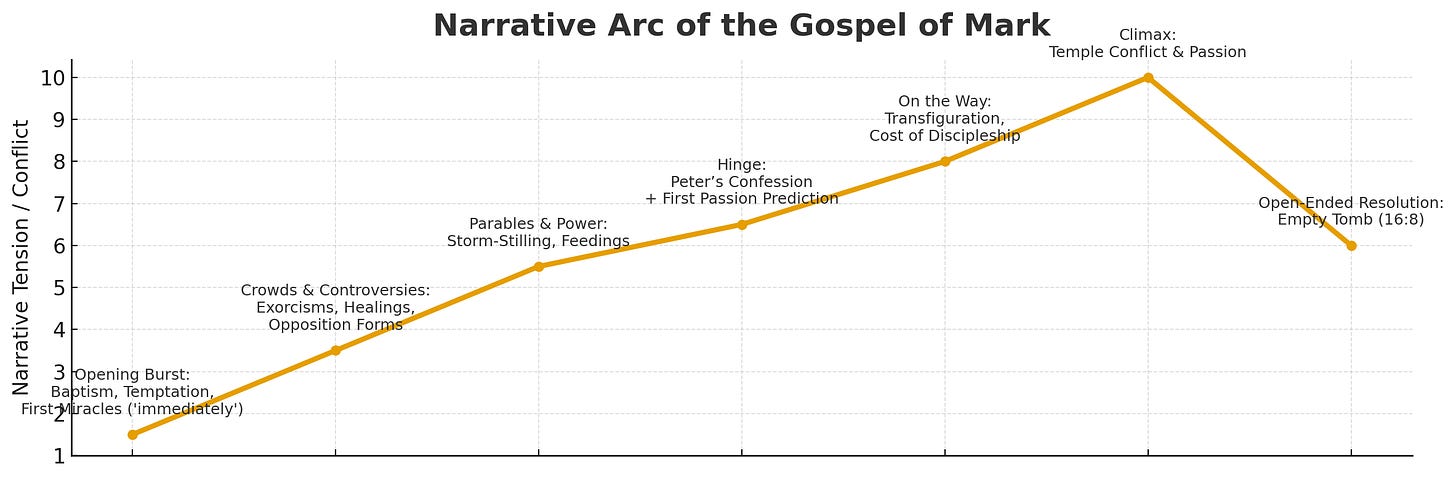

This isn’t the only way to depict the dramatic arc, but it’s useful to shake off the chapter and verse numbers and expose the overall thrust of the story hiding beneath. We can also do the same thing for Mark.

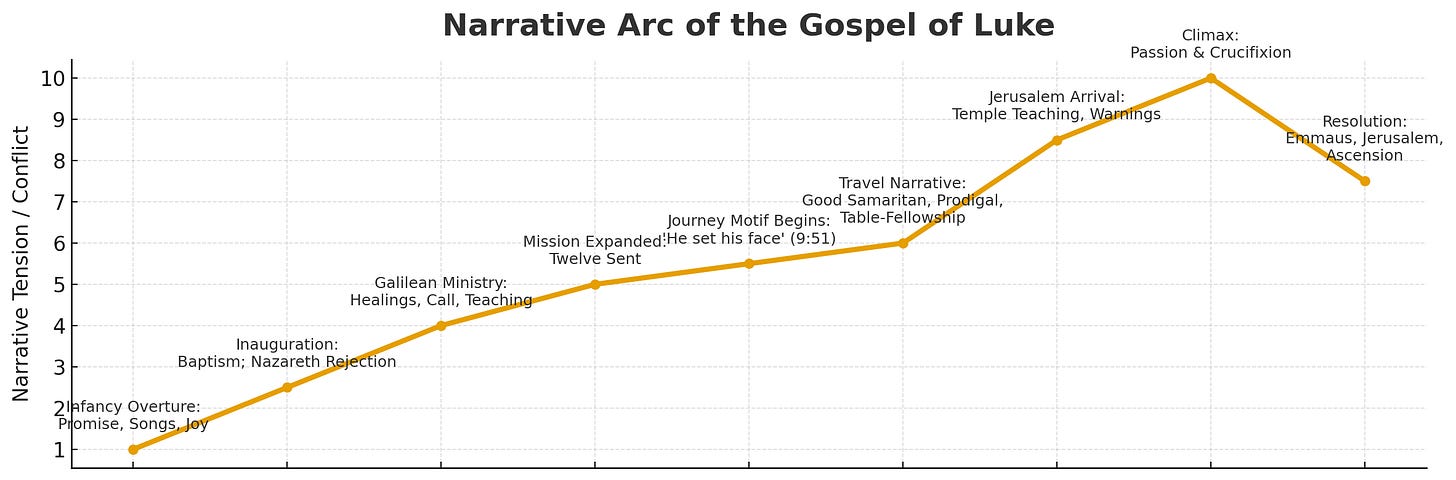

And Luke.

And John.

You can certainly craft (and depict) these story arcs differently; there’s no one right answer. But I wonder as we complete Mark this week and start Luke if you notice more of how the different gospel writers intentionally use literary devices and structures to accomplish different ends.

And now the floor is open to you: Please share anything from this week’s reading—or beyond it for that matter. What did you see in Matthew 16—Mark 9?

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with a friend.

More remarkable reading is on its way. Don’t miss out. Subscribe for free today.

If you want to read along with the September gospel project, here’s the schedule we’re following:

Week 1

Sept 3: Matthew 1–3

Sept 4: Matthew 4–6

Sept 5: Matthew 7–9

Sept 6: Matthew 10–12

Sept 7: Matthew 13–15Week 2

Sept 8: Matthew 16–18

Sept 9: Matthew 19–21

Sept 10: Matthew 22–24

Sept 11: Matthew 25–28

Sept 12: Mark 1–3

Sept 13: Mark 4–6

Sept 14: Mark 7–9Week 3

Sept 15: Mark 10–12

Sept 16: Mark 13–16

Sept 17: Luke 1–3

Sept 18: Luke 4–6

Sept 19: Luke 7–9

Sept 20: Luke 10–12

Sept 21: Luke 13–15Week 4

Sept 22: Luke 16–18

Sept 23: Luke 19–21

Sept 24: Luke 22–24

Sept 25: John 1–4

Sept 26: John 5–7

Sept 27: John 8–10

Sept 28: John 11–13Week 5

Sept 29: John 14–17

Sept 30: John 18–21

I’ll be posting a read-along thread every Monday so we can all share what we’re finding as we read. Next week, we’ll cover the rest of Mark and half of Luke (through chapter 15). Make sure you leave any thoughts about Matthew 16—Mark 9 below.

From Matthew 16 through to the crucifixion, as we read about the Transfiguration and eventually the entrance into Jerusalem, Jesus seems to become "grumpier", more and more frustrated with the disciples. He repeats things to them and they still don't get it. I find this change -- from patience to impatience -- understandable as Jesus seems to be running out of time. The "final exam" is coming soon and the students are not prepared! (Also, stepping back, I continue to be impressed with the humility of the gospel authors -- they are willing to admit that the disciples didn't get it....)

I get your point exactly here, Joel. As I mentioned last week, I'm reading the New Living Translation in an edition published by Alabaster Press. The verse numbers are very unobtrusive, and I was able to read Matthew as a unified story, which made a huge difference. I felt like I was sitting across a table from Matthew, and he was excitedly telling me everything he knew about this guy Jesus.