Protesting the Decline of Reading

College Students Are Reading Less Than Ever, Same with Adolescents, Same with All of Us. What’s Going On?

As protesters continue to make noise on college campuses, the Chronicle of Higher Education asked 22 professors to recommend one book each for incoming freshmen as they prepare to wade through the commotion. Makes sense: Understanding any situation requires context, and books are a great way to immerse oneself in a subject deeply enough to pick up necessary details and useful perspectives.

Predictably, most of the suggestions involve the present conflict and its historical backdrop. Yet surprises dot the list. A few professors recommended books channeling the antiwar protests of the ’60s and ’70s, which could provide both a model and a corrective; anyone of any politics would, for instance, benefit from wrestling through Saul Alinksy’s Rules for Radicals.

Martin Luther King Jr.’s Letter from Birmingham Jail and Henry David Thoreau’s Civil Disobedience? Deservedly on the list. But a couple of suggestions betray expectations in more artful ways than even these. One Georgetown history professor recommended the poetry of Nobel laureate Wisława Szymborska, who wrote about World War II and Communism from Poland, a country that endured the ravages of both.

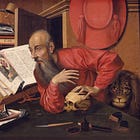

Another professor pointed to a revolutionary whose movement is still underway two millennia later. Dorian Abbot, University of Chicago professor of geophysical sciences, recommended the Gospel of John, saying,

St. John’s rich, beautiful, and multilayered account of the Gospel story would provide an excellent springboard for incoming freshmen to turn away from Dostoyevsky’s demons and toward the eternal questions, fostering life-sustaining spiritual development and freeing them from possession by the terrible ideologies that are causing this unrest.

But will anyone read it—or any of these books? Just eight days before publishing this aspirational reading list, the Chronicle published a report by Beth McMurtrie undercutting any reason for hope.

Dead Letters

I’m 48, so I’ve been out of college more than two and a half decades. But I can recall an undergrad class of American government at Sacramento State taught by T.L. Putterman in my junior year. There was no assigned textbook as such. Instead, Putterman assigned (if memory serves) nine books from which we read Edmund Burke, John C. Calhoun, the American Puritan fathers, William Graham Sumner, Edward Bellamy, and others.

I doubt Putterman is still teaching, though he was a good teacher. I also doubt today’s students would read nine books for a single class, or even significant portions of nine books—or even a significant portion of five books. Professors report students arriving at class unwilling and even unable to read much of anything, according to McMurtrie’s report for the Chronicle.

Her exposé, worth reading in full, sheds light on why. Here are several suggested drivers for students’ poor literacy. Note that these are all upriver problems, starting in grade school and high school.

Learning loss during the COVID pandemic as lockdowns, quarantines, and illness disrupted schooling.

The lowering of academic expectations in the wake of No. 1, including a general deemphasis on reading, writing, and standards more generally.

Educators’ reliance on unproven instructional models to teach reading, favoring so-called “balanced literacy” and context clues over phonics.

Educators being encouraged to teach to the test, rather than teach critical engagement with texts in their entirety.

Incomplete high-school instruction in foundational areas of knowledge such as history and science, leaving students with less intellectual resources to bring to bear in college.

The decline in kids reading for fun, affecting both the scale and skill of potential readers as they enter college.

The profusion of smartphones, as nearly all students have distraction engines in their pockets—or, more accurately, in their faces while they increasingly punt class assignments to the curb.

Theresa McPhail, an associate professor at Stevens Institute of Technology, says teachers should “meet your students where they are.” But, as McMurtrie reports, she also says if reading skills decline any further, “she’ll feel like a cruise director organizing games of shuffleboard.”

Smartphones, Dumb Kids?

I’m unconvinced by No. 7 on the list. I’m not downplaying possible negative effects of smartphones, and I’ll share one in a moment, but the stats on kids reading for fun complicates the simple smartphone-equals-problem narrative.

In 1984, 35 percent of 13-year-olds folded pleasure reading into most days, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress, highlighted by McMurtrie. By 2012, the number had dropped to 27 percent. It was down another 10 points by 2020 at just 17 percent. The key detail? Note the decline before 2012, Year Zero in Jonathan Haidt’s compelling story of societal capture by smartphones.

More telling, these number also drop off for kids even when they don’t have phones. In both 1984 and 2012, according to the NAEP, 53 percent of nine-year-olds said they read for pleasure most days. By 2020, that had dropped 11 points to just 42 percent, numbers paralleled by a report from the children’s publisher Scholastic. But as Dan Kois notes in an article for Slate, most of these kids won’t have smartphones until they’re 11 or 12.

Something more significant is happening, and it involves the rest of the educational methods and policies on the list: lowering standards; the deemphasis on phonics; the move away from immersive reading toward shorter, decontextualized passages; teaching to the test, and so on. Even the eager embrace of online learning might be having an effect, since reading on screens seems less helpful for comprehension than reading print on paper.

The most important item on the list, however—incomplete instruction in other subject areas—might be the easiest overlook.

The Wrong Focus

If we want kids to be able to read more Jane Austen and Hemingway, or understand longer prose narratives about the way the world works, we shouldn’t belabor literacy as a subject but rather emphasize the acquisition of facts and knowledge.

“What does comprehension require?” asks University of Virginia psychology professor and reading authority Daniel T. Willingham. “Broad vocabulary, obviously. Equally important, but more subtle, is the role played by factual knowledge.” Decoding is one thing, understanding another.

“Third-graders spend 56 percent of their time on literacy activities, but 6 percent each on science and social studies,” says Willingham. “This disproportionate emphasis on literacy backfires in later grades, when children’s lack of subject matter knowledge impedes comprehension.” We should be using “high-information texts in early elementary grades,” he says. “Historically, they have been light in content.”

Knowledge is a web of associations. If kids don’t have enough facts to work with, they can’t grasp what they read. As the complexity of plot lines and ideas magnifies through the ascending grades, kids get stranded on shoals of incomprehensibility and—reasonably enough—disengage. If you want college students who can read much of anything, you need to feed grade schoolers more science, civics, history, even philosophy and religion. All literacy depends on cultural literacy. Kids can understand Plato’s myth of the cave as easily as anyone, and it’ll help them understand much, much more later on.

We can take smartphones out of schools, but it won’t help these more foundational issues. The only way to learn to grapple with complicated storylines and ideas is, well, grappling with complicated storylines and ideas. And the most efficient means of doing so is immersion in long-form reading as early as possible.

What about Us?

The always-interesting

weighs in with several additional reasons kids may be dropping their books. As a parent, one in particular stood out for me. “Maybe the kids likely to read are overscheduled,” she says, “with too little free time to discover and enjoy books.” I’ve got five kids, all of whom have either been through school or are still in it. I can confirm: Overscheduling is a real phenomenon.Reading is primarily an interstitial activity, but if we’ve engineered all the nooks and crannies out of the schedule, cramming our kids’ days with programs and activities, it’s no surprise they don’t find much time to read—even those who are favorably inclined. And this is where I would pooh-pooh smartphones.

In that fifteen- or twenty-minute window in the car between school and the recital, practice, game, or whatever, kids are increasingly turning to their phones instead of books. Who can blame them? That’s the ongoing story they want to get back to, whether it’s the influencers they follow on Instagram and TikTok, or their friends in the group chat.

Blame belongs with the people who killed the calendar while modeling poor phone use (hint: that would be us, parents). In a real sense, this whole problem is our fault. Our kids losing interest in reading is just another loop in a vicious cycle that starts with us losing interest.

Reading starts in the home. “Studies looking at ‘family scholarly culture’ have found that children who grew up surrounded by books tend to attain higher levels of education and to be better readers than those who didn’t, even after controlling for their parents’ education,” writes Joe Pinsker in the Atlantic.

Why? It’s not only a question of modeling the behavior, though that’s part of it. Parents in more bookish homes also tend to talk to their kids about what they read and share information more broadly, which plays directly into the question of kids having ample background information about the world. The more context kids have, the easier it is to decipher texts on their own.

But more than two thirds of Americans, according to a YouGov survey, say they read just 10 books or fewer a year. About a third read one or none. Is it any surprise that kids growing up in bookless homes show little interest in reading? They have neither the model nor the information, and schools decreasingly provide either, so they’re not backfilling the deficit.

Worth noting from the survey: “The more recent an American’s childhood, the less likely it was to involve reading books,” which is to say, this chart is going to look much worse in 20 years.

So might our world.

What’s at Stake?

Whatever the cause, we’re obligated to address the underlying issues both in our homes and in our schools. And there’s reason to assume we’re in significant trouble if we don’t. As Adam Kotsko, who teaches the Great Books at North Central College, says,

The world is a complicated place. People—their histories and identities, their institutions and work processes, their fears and desires—are simply too complex to be captured in a worksheet with a paragraph and some reading comprehension questions. Large-scale prose writing is the best medium we have for capturing that complexity.

It’s easy to roll our eyes at college students who opine on the world without understanding it. But, then, we haven’t equipped them. And through our parenting and schooling we might actually be stymying their ability to develop the necessary skills to form reasoned judgments. Public debate is about to get even less fun and more irrational than it already is.

Democracy’s not a contact sport, but we’re headed that direction.

There’s no easy answers to any of this. Systemic problems are tough to unwind. But we do have a small gift stretching out a few months before us. Here’s one thing we can do to protest the decline of reading: Encourage our kids to read this summer. They’ve got weeks and weeks without class assignments, weeks and weeks where there’s more air in the schedule. Head to the bookstore or library and let them find something that piques their interest. Whatever it is, get it and let them read it—and the next book, and the next book, too.

Thanks for reading. Please hit the ❤️ icon. And while you’re at it, spread the love and share it with a friend!

If you’re not already a subscriber, take care of that now. It’s free, and you’ll do a cartwheel when the next installment hits your inbox.

Before you go, check these out:

Children should see their parents reading books every day.

My Dad read the newspaper. My Mom never read books, but once they discovered audio books in their daily commute, suddenly they were reading dozens of books each year.

My children have grown up with a library of hundreds of books in the home. They have watched both parents ingest stories and information every day. They were at the table when we discussed ideas from those books.

Both my children read. I think theirs will, too. 📖

This was so great and confirmed a lot of what I've felt. And helps me to feel confident in our choice to homeschool and how we do it.