Bookish Diversions: Polarized? Yes. Politicized? Please, No

Vonnegut Museum Vandalized, Jerzy Kosinski’s Worry, Thought Police, C.S. Lewis = Dangerous?

¶ Wresting freedom from each other. An unidentified masked vandal chucked a rock through the street-facing glass door of the Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library in Indianapolis, Indiana, last week. Police are still seeking suspects, but museum administrators believe the attack came in response to the organization’s public statements against book banning, an example of which you can find here:

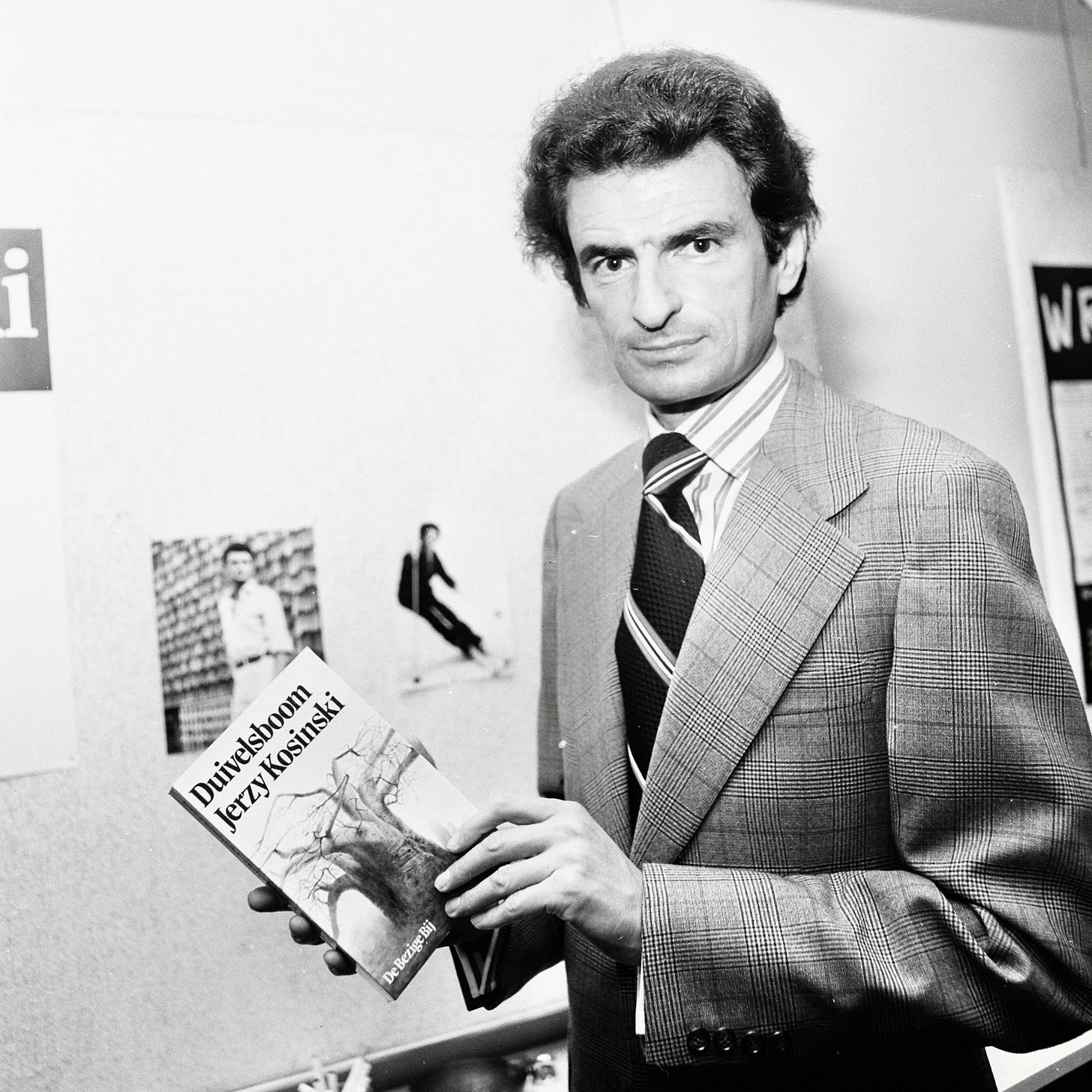

If so, it’s ugly evidence for a trend identified by another novelist, Polish-American literary lighting-rod Jerzy Kosinski.

Growing up in Eastern Europe and studying in the Soviet Union, Kosinski faked his papers and emigrated to America in 1957, where he became a proud citizen and earned acclaim as a writer. He won the National Book Award in 1969 for his experimental novel Steps. “When I flew to New York yesterday from Europe,” he said in his acceptance speech,

I recalled a similar trip that I made twelve years ago. In the decade that has passed, not much has changed on the other side of the Iron Curtain. But much has changed here in America. Then I—perhaps more than others—saw America as a free country.

I still see it that way—but it is a different America now. It has become polarized, as Europe has been for centuries. Americans are no longer the same. They are less anonymous. They wrest freedom from each other. They clearly delineate their places in society. They are angry, violent and abusive. They have become political. And the system responds in turn and invades their freedom.1

Kosinski said that half a century ago, but his words paint an uncomfortably accurate portrait of our present situation. Reflecting on Kosinski’s speech today, however, it occurs to me that polarization isn’t the problem. At least not by itself.

We live in a big, fat, free country, filled with all sorts of people. Disagreements—even vigorous ones—are bound to exist in a free and pluralistic society like ours. I’d go so far as to say they’re evidence we’re doing something right. The problem lies in another phrase:

They have become political.

In a free country, polarization is inevitable. That’s good; my values might not be the same as yours and probably aren’t. That’s not a problem until one of us uses the political machine against the other.

Unfortunately, that happens with disturbing regularity today. Not only are people mobilizing in school districts across the country to ban books, but governors and state legislatures are increasingly involving themselves. “Bills seeking to ban certain books from school libraries are popping up in multiple states this legislative session,” says Elaine Povich, following the story for Stateline and providing several examples.

Consider again Kosinski:

Americans are no longer the same. . . . They wrest freedom from each other. . . . They are angry, violent and abusive. They have become political. And the system responds in turn and invades their freedom.

Both Kurt Vonnegut and Kosinski represent a mid-to-late-twentieth century liberal consensus that freedom of speech is a near-sacred value. They, along with those who assumed the view, came of age when authoritarian regimes in Europe imposed brutal controls on speech and drastically limited expression. To Vonnegut and Kosinski censoring speech was a hallmark of the authoritarianism the first fought in World War II and the second fled a decade later.

You can imagine them both asking, dolefully, how could Americans become now what their nation opposed then, whether by petty acts of vandalism or people wielding the country’s political machinery against each other?

¶ Thought police. One track the conversation on censorship runs is the move toward revising language from yesteryear deemed offensive by some today. I’ve addressed the impact of “sensitivity readers” here before, regarding the decision to edit passages of Roald Dahl’s children’s stories and Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels. The most recent example are changes made to Agatha Christie’s catalog. Some are considerably unhappy about these changes.

Such decisions are complicated by commercial concerns, but the background considerations are worth attention. In keeping with my statement that polarization is good, here’s a mostly positive look at the role of sensitivity readers in publishing, and here’s a vigorous takedown. I’m, er, sensitive to the concerns of both sides but come down on the side of saying what you want how you want and accepting the consequences.

¶ C. S. Lewis, Domestic Terrorist? The unnerving part of this whole free-speech debate comes to a head when these two issues combine. Book bans function in the political space, and sensitivity readers function in the commercial space. But you can imagine a frightful overlap. A UK antiterrorism department has released a list of books supposedly favored by far-right extremists. The list includes not only C. S. Lewis but also J. R. R. Tolkien, Aldous Huxley, Joseph Conrad, and—either ironically or predictably, depending on how you look at it—George Orwell. One problem with subjecting reading to the political process is that the political process can always be used against you. And will be.

the system responds . . . and invades their freedom.

How far will such invasions go? That largely depends on how much freedom we insist on wresting from our neighbors in the meantime.

¶ Thanks for reading. Please consider sharing this post with a friend.

And if this post resonated, try “What Else Can We Censor While We’re Here?” as well.

¶ Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Jerzy Kosinski, Passing By: Selected Essays, 1962–1991 (Grove Press, 1995), 39.