Our Ancestors Murdered Their Mother Tongue, Thankfully

Reviewing Laura Spinney’s ‘Proto: How One Language Went Global’

At the beginning of the musical My Fair Lady, professor Henry Higgins points to native English speakers’ wild mispronunciations and laments “the cold-blooded murder of the English tongue.”

Linguistics is, says Higgins, both his profession and hobby. As such, he’s hypersensitive to variability in usage and pronunciation. What’s more, he assumes there is an elevated, true, and proper sort of English from which all other expressions shift and wobble downward into incomprehensibility.

“There are even places,” sings Higgins,

where English completely disappears.

Well, in America they haven’t used it for years.

Higgins regards such slips from the Olympian heights as phonetical, syntactical, even moral lapses. For the professor improper use of English represents a failing. But that’s hogwash.

Slipping through Time

Higgins cuts a comic figure and we know to laugh at his pedantry. Still, many of us play the same games, scrutinizing the propriety of others’ expression and passing judgment along the way; some treat it like a sport where they hand out medals. We’re every bit as goofy as Higgins.

But English can’t be murdered; it simply changes. There’s a glaring example right there in that wonderful song we’ve already quoted, “Why Can’t the English?” Pointing to Eliza Doolittle, Higgins sings:

Look at her, a prisoner of the gutter

Condemned by every syllable she utters

By right, she should be taken out and hung

For the cold-blooded murder of the English tongue

Hung? Professor, as I’m sure you know, that’s supposed to be hanged.

While hang might masquerade as a single verb in modern English, it comes from two separate Old English verbs: the strong, transitive verb hōn (to cause someone to hang, to put to death by hanging) and the weak, intransitive verb hangian (to hang, to be suspended). The verbs not only described different actions, they also had different past-tense forms: hanged for the first, hung for the second.

In Middle English the two verbs merged, enabling Shakespeare to tease a bawdy laugh from the ambiguity in Twelfth Night. When Maria warns the fool Feste, “My lady will hang thee for thy absence,” he shoots back, “Let her hang me. He that is well hanged in this world needs to fear no colors” (act 1, scene 5). The gag turns on the slippery sense of the word: to be (a) jerked by the neck and (b) endowed below the belt.

Thanks to the semantic sloppiness, Shakespeare gets two meanings for the price of one, letting hanged and hung collapse into the same punchline. But not for long!

If English offered the Bard a seventeenth-century playground, it served as an eighteenth-century battleground for bossy, prescriptivist grammarians—people like Higgins. Manuals and dictionaries soon laid down the law: Pictures are hung, they said, but people are hanged.

Arbitrary, yes, but suddenly a matter of life and death—literally. “We hung the curtains; we hanged the murderer.”

Of course, Higgins would have known this. My Fair Lady’s lyricist was having his fun. But the joke highlights the absurdity of the professor’s position. Even a verb as simple as hang betrays centuries of drift and evolution in correct understanding and usage. And we’re only getting started.

Modern English was once Middle English, which was once Old English, which was once some form of Germanic before that. Every language is the bastard child of another, sometimes many others. Spanish and Italian? Just Latin for different times and climes. Push back farther, and Germanic and Latin themselves slip into the same ancestral soup. And if we scrape the bottom of the cauldron? We reach our Mother Tongue, what specialists call Proto-Indo-European.

Picturing Professor Higgins on this timescale—conveniently and capably covered by science writer Laura Spinney in her book Proto: How One Ancient Language Went Global—is to imagine an impossibility.

Kissing Cousins

For all of his righteous indignation, Higgins is up against forces he cannot best or control. Take hang. Not only can we find the verb in Old English, we can locate Old Norse and Gothic cousins. And linguists can trace it even further back, which you might imagine given its spread; versions of the word actually appear in Latin (cūnctārī, “to delay”), Hittite (gang-, “to hang”), and Sanskrit (śáṅkate, “to be in doubt, to hesitate”). All these forms ultimately go back to the ancient Proto-Indo-European *ḱenk-, which meant to waiver or be held in suspense. Darkly humorous—that “dally” would eventually mean “dangle till dead.”

Spinney’s Proto shows us how this migration of meaning and sound occurred. She mentions for instance, the case of Hadrian addressing the Roman Senate around 100 CE. Born in Spain, the future emperor spoke with laughably inflected Latin.

“There are even places,” I can hear the onlookers snigger,

where Latin completely disappears.

Well, in Seville they haven’t used it for years.

And true enough some centuries later—after Latin had more thoroughly morphed into its various daughter tongues. When Charlemagne’s grandsons formed a treaty, one of the men spoke Romance, which had deviated from Latin by the ninth century so much as to be gibberish to the other who spoke German but knew Latin.

“Linguists,” says Spinney, “consider that on average it takes between five hundred and a thousand years for a language to become incomprehensible to its original speakers (who are, obviously, no longer around to look bemused).” We can, for instance, manage Shakespeare but—hwæt!—require translators for Beowulf.

With all the distance between the two languages, the trick is recognizing that Feste and Grendel share a lingual connection. The problem? If the original speakers aren’t around to correct everyone’s pronunciation, in time people fail to notice the relationship between the old and the new. Instead of tongues on a continuum, they strike the ear as separate entities—now requiring investigative work to uncover and recover the connections.

It was Dante who first noticed the relationship between Latin and the later Romance languages, such as his Tuscan dialect, French, and Spanish. Around the same time, scholars realized the family ties between the various Germanic languages and their common ancestor. But the real leap? In the late eighteenth century, the British judge William Jones found himself in Calcutta and began to notice similarities between humdrum tongues—such as Latin, German, Greek, English—and the ever-exotic Sanskrit.

Spinney offers us several Latin–Sanskrit comparisons so we can see for ourselves:

House: domus, dam

God: deus, deva

Mother: mater, mata

Father, pater, pita

King: rex, raja

That couldn’t be a coincidence, could it? Definitely not, especially once Jones’s contemporaries realized dictionaries and lexicons oozed with similar examples. Jones wasn’t the first to spot the relationship but, as Spinney says, the world finally started paying attention.

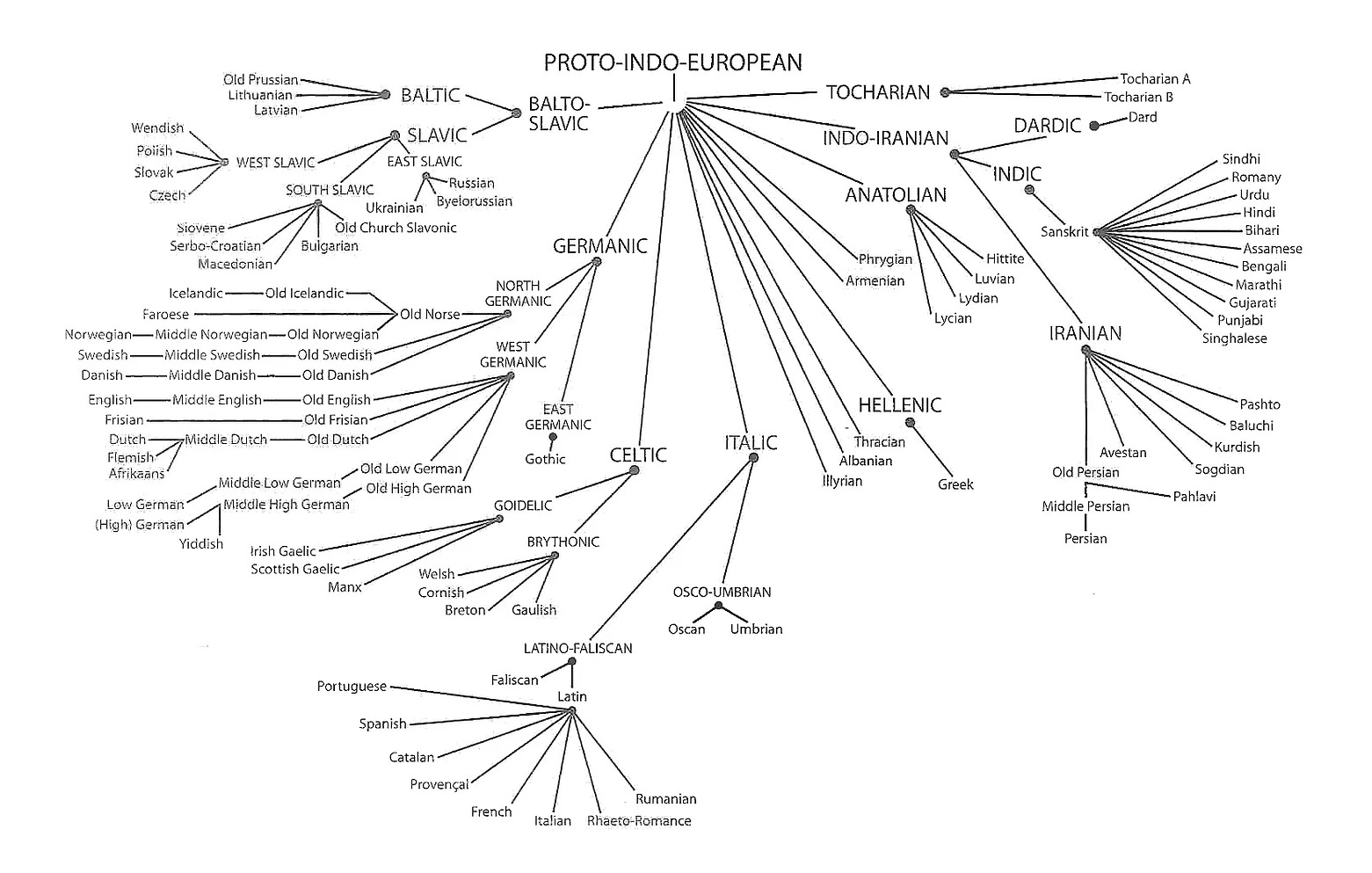

It wasn’t that Sanskrit gave birth to Latin, Greek, German, or what have you. Rather, Sanskrit was a distant cousin of languages that for reasons of geography or ethnicity seemed to share nothing in common. Same with many others: Bengali, Swedish, Polish, Hittite, Portuguese, Greek, Persian, French, Catalan, Russian, Dutch? All cousins.

How could that possibly be?

Back Home to Mother

As the Brothers Grimm traipsed through Germany collecting fairy tales they hoped their research would reveal a form of ancestral German. Working with earlier insights from Friedrich von Schlegel and Rasmus Rask, Jacob Grimm developed a series of rules that seemed to describe how sounds behaved in languages over time, how for instance a p sound in Latin became an f in Germanic languages.

Latin may have pater for father, but Old English developed fæder, Old High German fater, Old Norse faðir, and Old Dutch fadar. Rules such as Grimm’s Law allowed linguists to establish relationships between all those cousins—and those much further afield. “The sound laws work,” says Spinney,

because speech sounds drift over time, but the human vocal tract is not capable of an infinite variety of sound combinations. The directions in which individual sounds can drift are limited, and if one sound changes it tends to carry its neighbours with it. Guided by these laws, which restrict the possible ways languages can diverge from a common ancestor, linguists could start to identify inherited features shared by related languages, even if they sounded quite different in each.

Language contains, as she says, “an archive of its own journey.” And here’s where it all gets wild. Because these sound rules have proven so durable and reliable, linguists have been able to use them to run the tape of language development backward—not just to, say, Old English, Old Dutch, or other Olds for which we have written texts, but also into the land of the speculative and hypothetical.

Since Old English and Old Dutch didn’t come from Latin, or Sanskrit for that matter, there must have been a prior language from which they all inherited their similar words for father—fæder, fadar, pater, pita—not to mention gobs of other common bequests. “Gradually,” says Spinney,

the linguists developed a sense of the relative age of linguistic features—certain sound combinations, say, or grammatical devices—based on whether they were present in older or younger branches of the family. This allowed them to attempt the delicate task of reconstructing long-dead proto-languages—the common ancestors of the twelve main branches and ultimately the mother of them all, Proto-Indo-European.

It’s taken decades and decades to work out the details—and the work and all its heated arguments continue—but what eventually emerged was a vast evolutionary web of languages all pointing back to a common Mother Tongue, basically what you see below.

Urdu and Hindi are mutually unintelligible to Spanish and Flemish speakers, but the languages are related nonetheless. Unfortunately, linguistics can only illumine part of the connection. Scholars rely on a mix of archeology and genetics to fill out the picture.

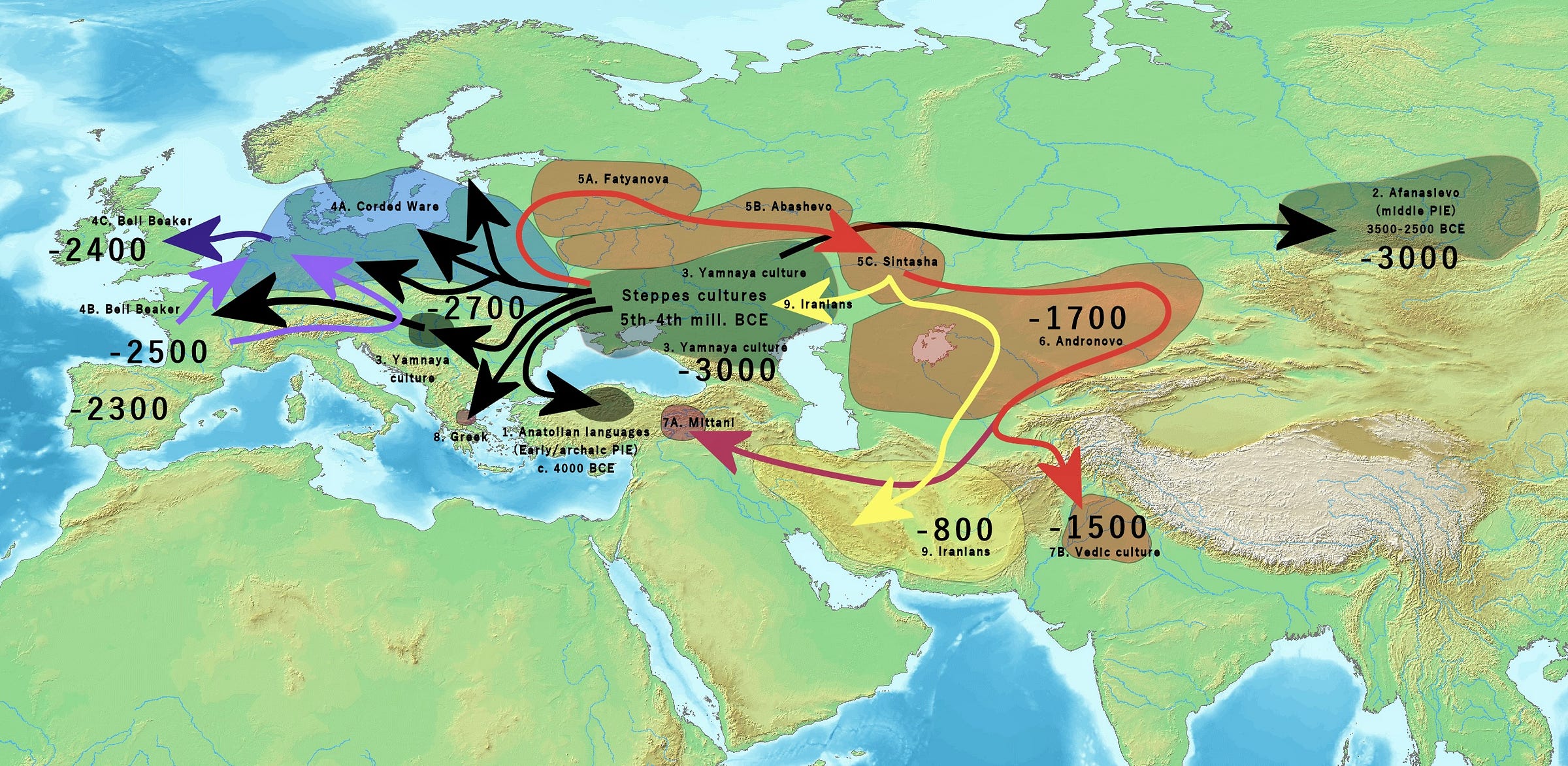

Beginning most likely on the Eurasian Steppe with a very small number of speakers about five thousand years ago, Proto-Indo-European spread outward through a series of jaunts and migrations. Chapter by chapter, Spinney follows the trail:

Anatolian

Tocharian

Celtic, Germanic, Italic

Indo-Iranian

Baltic and Slavic

Albanian, Armenian, Greek

Imagine Professor Higgins accosting speakers at various points with a warning to mind their fricatives. The slow moving tsunami of change would have simply washed over all his objections. As Eliza Doolittle would sing,

Just you wait, ’inry ’iggins, just you wait.

You’ll be sorry, but your tears will be too late.

All of this is easy to see in retrospect, however much we might still argue over this or that point, and some reviewers have taken issue with Spinney’s summation of the work. The virtue of Spinney’s Proto is to bring centuries of discovery and theorizing, drama and debate into a digestible and enjoyable package, ideal as a starting point for nonspecialists.

There’s no reason to accept Higgins’s framing of linguistic change as murder; though if we’re forced to go along with it, we’d have to say the death was justifiable—or at least that it turned out okay in the end. Indo-European is now the largest langauge family on earth. Counting secondary speakers, nearly every second person on the planet speaks Indo-European.

Proto details how that happened, revealing along the way that Higgins’s framing is preposterous. Languages don’t die, and they can’t be murdered. Thankfully, they do evolve.

Thanks for reading and shaping the community here at Miller’s Book Review 📚. If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ icon and share it with a friend and discuss it below.

More remarkable reading is on its way. Don’t miss out. Subscribe for free below.

I love this post with a thousand hearts!

Masterful short tour of a big subject. Then, there’s Basque, which I half suspect is derived from Neanderthal.