First Thing We Do, Let’s Kill All the Copy Editors?*

What Editors Do, Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Roberts Caro and Gottlieb, Clarice Lispector, More

Nassim Nicholas Taleb, author of such bestsellers such Fooled by Randomness and The Black Swan, famously dislikes copy editors. He tweets about his distaste. He even writes about it in his books.

In Antifragile, for instance, he identifies “copy editors trying to change your text” as an undesirable intervention like bad foreign policy, central economic planning, overmedication, and helicopter parenting. The dreaded cost? “Blander . . . commodified writing.”

When he finished the manuscript for Skin in the Game in 2017, he tweeted, “Done! . . . Now copyediting & fight with copyeditors.”

In the book itself he presents “copy editors” in a table along with “writers, (some) editors,” and “real writers.” He files the first under “No skin in the game,” along with bureaucrats, consultants, politicians, and bankers. It’s almost like he’s picking that anticipated fight.

There are basically three tiers of editorial work in publishing, each corresponding to a stage of refinement in the work: substantive (or developmental) editing, copy editing, and proofing. Taleb’s complaint seems to focus on the first two, especially the second.

I’ve done both.

Book Doula

A substantive editor works with the author’s big-picture ideas and arguments. Writers call them when they get stuck. And they go over the draft to ensure it holds together once the author files their manuscript, hopefully on time.

Conversations might include recommendations to reorder passages if the flow falters, to cut a section if it’s not really adding to the book, or to develop a thought if it’s not up to snuff. Does this work? Will a reader get lost? Does the reader care? Will they fall asleep? “Meandering.” “Doesn’t connect.” “Move to chapter 8.” “Cut chapter 8.” “You’ll need stronger evidence to make that claim.” “The whole thing plays better if you. . . .”

Given their work with the MS, the substantive editor exists on a spectrum somewhere between critic and technician. Given their work with the author, somewhere between therapist and doula.

“The editor represents many things, and different things to every writer,” says famed Simon & Schuster editor Robert Gottlieb, subject of a recent documentary covering his decades-long publishing relationship with bestselling biographer Robert Caro.

It’s a financial relationship. It’s an approval relationship. It’s a technical relationship. It can be a close one or it can not. Some writers don’t want to be social with their editors. Others need to talk to them constantly. . . . So your job, being a service job, is to supply the writer with whatever you intuit he or she requires and needs and can make the most of.

You can get some genuine puzzlers. I had an author who worked only by fax machine—not easy to find even then. I had another who refused to use paragraphs; he wanted every sentence to start a new line. “That’s how I communicate,” he told me. “That’s not how people read,” I said.

My boss and mentor, Brian, had an author exactly the opposite. He turned in a complete manuscript with no paragraph breaks at all. The author had some clout because of prior book sales, and his agent made Brian’s job all the harder by exclaiming in an email to both Brian and the author how brilliant the book was. Guaranteed he hadn’t read more than a page.

Finer Points

Once the substantive editor is done with their pass and the author has addressed their concerns, it goes to the copy editor. This pass concerns finer points of style, such as bringing the book into alignment with The Chicago Manual of Style—large as the Bible and nearly as authoritative.

Nonspecialists might struggle to appreciate the particulars, but they benefit from all those rules and rubrics every time they crack open a standard trade book, where inconsistencies and infelicities have been rubbed out to prevent them impeding the author’s point. (Copy editor Jeff Reimer offers a helpful article on the process.)

Based on his complaints, this seems what Taleb finds most irksome. Why? First, he says it dulls the writing. One man’s infelicity is another man’s favored choice of expression. And there’s neither romance nor adventure without some inconsistency.

The problem, according to Taleb, stems from the arbitrary power the copy editor exercises over his prose. As he says in Antifragile,

If you supply a typical copy editor with a text, he will propose a certain number of edits, say about five changes per page. Now accept his “corrections” and give this text to another copy editor who tends to have the same average rate of intervention (editors vary in interventionism), and you will see that he will suggest an equivalent number of edits, sometimes reversing changes made by the previous editor. Find a third editor, same.

He might not be wrong. I’ve never tested the point, but I can imagine handing a page to Copy Editor A, accepting all their tweaks, and then handing the edited page to Copy Editor B only to receive another round of adjustments—like a building inspector who has to find something wrong on every job site.

The copy editor works in a world with fewer absolute rights and wrongs than you might imagine. Instead, there are longstanding conventions and individual tastes. Rightly, wrongly, whateverly, Taleb seems to hate that someone external to his manuscript has that much influence over his manuscript. He’s not alone.

And I get it. No copy editor would have let me get away with “whateverly.” But as a former publishing professional and a writer who continues to work with both substantive and copy editors, I also disagree.

Known by Their Absence

As I mentioned, I’ve done both kinds of editing, and I can’t tell you the amount of misery and irritation copy editors spare this undeserving world.

To most people, they’re just phrases and punctuation. Words! Toss them together and say what you want. To a copy editor, however, they are potential sinkholes and land mines, sabotaging any hope of clear communication.

Some writers are too clever for their own—or their readers’—good. Others, too unskilled. If you need evidence on this point, consider any self-published book before self-publishers got smart and started hiring copy editors. They’re unreadable. Every now and then I get a book published by a trade house which was underserved by its copy editor; the amount of wincing induced could result in lawsuits. Probably should.

Just like everyone hates the cops until an emergency, you know the value of a copy editor by their absence.

Does this address any particular traumas endured by Taleb? No. And who knows? Maybe he had some real duds who fought him on every joke, jab, and aside. He makes a lot of those; they’re part of what makes his books fun to read. And that’s the real point of tension here. Like the cops, editors sometimes go too far.

Where’s the balance?

Back-and-Forth

A lot of this comes down to how the author wishes to express themselves. Some writers deliver workaday prose to which a copy editor can do little harm. Sorry to say, it’s already bland and commodified. Others have elevated, even flamboyant, personal styles that can be ruined by an editor; I don’t, for instance, know how anyone edits David Bentley Hart. Probably by letting him say whatever, however he wants.

Still others think they have an elevated style, though they’re merely idiosyncratic and picky. But you know what? It’s their book, right?

No, not exactly.

The publisher is like a venture partner in the project, and the editorial team is one way they ensure their investment. When an author signs with a publisher, they’re welcoming them into their book. It’s like inviting a vampire into your house, perhaps, but there they are.

The trick is in deciding what changes have to be made to support the both readability and marketability of the book, while allowing the author as much leeway as possible to express themselves as they choose.

This isn’t always easy. I once had an author who wanted me to explain every edit in a 120,000-word manuscript over the phone. It took fourteen hours over two days, and I wanted to drill a hole in my head when I was finished. But he was happy, and he accepted most of my changes.

The back-and-forth is part of the process. That comes out strong in the Caro-Gottlieb story. “They bicker all the time, about every comma, period, and semicolon,” writes Gal Beckerman in the Atlantic. “Actually,” he continues,

don’t even get them started on semicolons. Gottlieb refers to a “civil war” that took place over the punctuation mark’s usage. The flintiness about every little thing is part of their shtick. “He does the work. I do the cleanup. Then we fight,” Gottlieb says in the film.

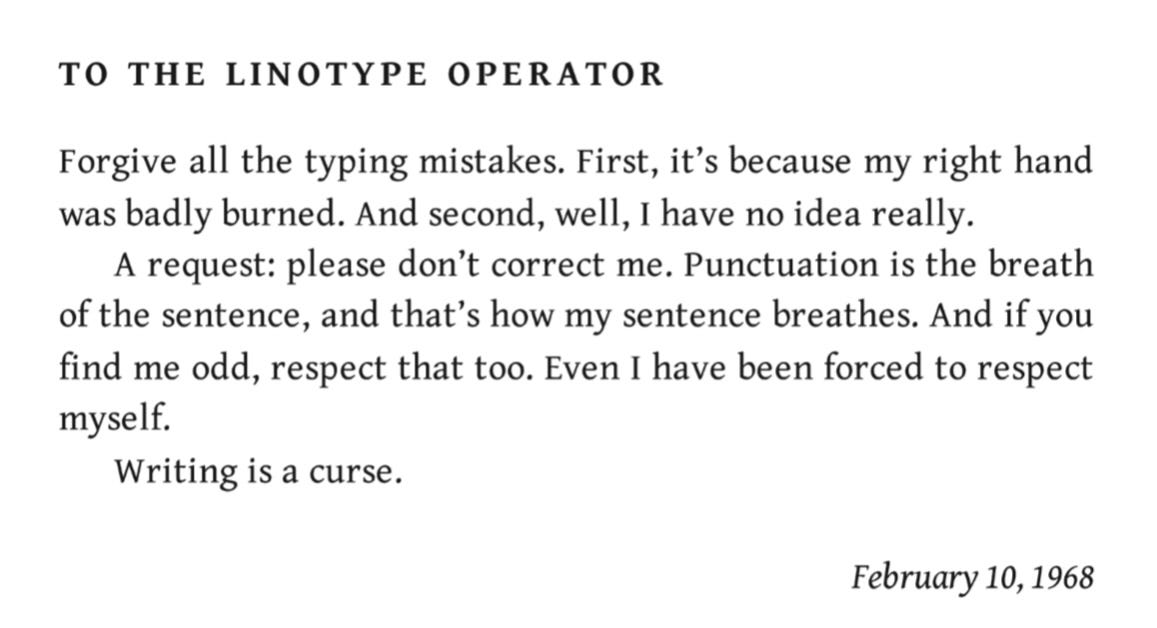

If you’re Taleb, you’d rather save your energies for other entanglements. Clarice Lispector, a Brazilian novelist and newspaper columnist, would have appreciated his stance. She once told the typesetter at her newspaper to leave her prose alone.

Mutual Respect

“Punctuation is the breath of the sentence.” It’s a lovely phrase. I trust no editor would mess with that one. And I hope they’d have adequate empathy for that last bit, too. It’s not exactly a curse. But formulating something worth saying and saying it in a way worth reading can be the hardest thing in the world. Thank God editors—copy editors included—are there to help.

And maybe Taleb gets that, after all. Despite his gripes, his acknowledgements for Skin in the Game mention three: “Will Murphy (editor, advisor, proofreader, syntax expert and specialist); Ben Greenberg (editor); Casiana Ionita (editor).” They must have done something right.

* With apologies to Dick the Butcher.

P.S. If you’re interested in learning more about what editors do, I recommend What Editors Do: The Art, Craft, and Business of Book Editing, an essay collection with a perfectly descriptive title, edited by industry veteran Peter Ginna.

Thank you for reading! Please share with someone you know who loves books.

If you’re not a subscriber, take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks, again!

This is my favorite of your posts so far! Probably because I just finished the final round of edits on my new book. But you left out the group that's even worse than copy editors: proofreaders. At PRH/Waterbrook, they send it to a couple of proofreaders AFTER all the copy editing is done, and then you have to deal with their "I didn't follow this," or, "You lost me there," comments. I had one that absolutely didn't get any of my humor, in chapters where the humor made the whole point... frustrating. My wife and I realized that the manuscript has to be readable by everyone, so some proofreaders need to be of different educational and cultural backgrounds than the writer.

At the end of the project, all the edits make the book "just right" for as many readers as possible. Grateful for editors! (And even proofreaders)

Thank you for another great post!

I kept meaning to get back to this one. Really great. I’m not an editor in any stretch of the imagination but I love the substantive part.