No Silos: The Challenge of Finding Your Audience

John J. Thompson Talks about Alternative Media, Creative Community, and the Challenges of Finding Your Audience

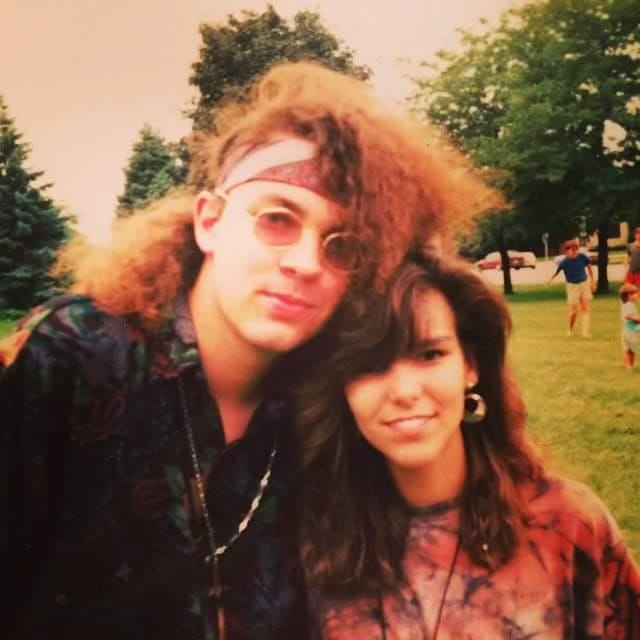

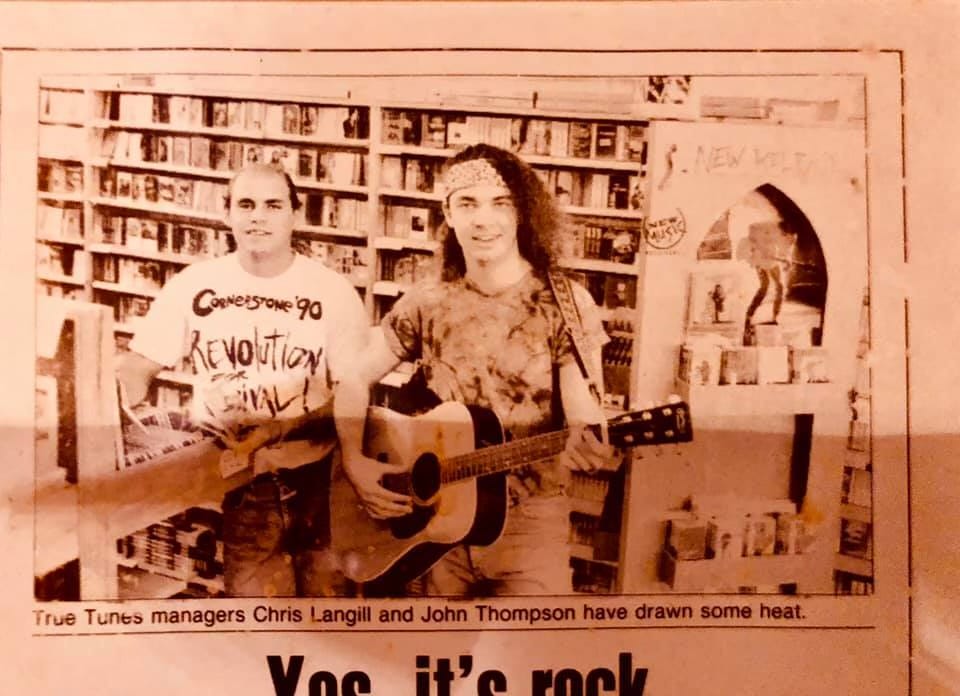

John J. Thompson tumbled down the music rabbit hole as a teen and never came out. I first encountered him through True Tunes, a magazine, music store, and concert venue he founded in Wheaton, Illinois, in 1989, focused on alternative music with a spiritual valence and other forms of faith-fueled art.

After shuttering True Tunes nearly a decade later he went to work for the Cornerstone Music Festival, and then Capitol Records, overseeing publishing in Nashville, Tennessee. After almost a decade at Capitol, he began a new and perhaps more surprising adventure in academia, first as the associate dean of the Trevecca School of Music and Worship Arts and now as a visiting professor of music industry studies at Lipscomb University.

All along the way, he’s made music of his own with his band The Wayside and offered creative consultation on movies and documentaries, including Electric Jesus; Parallel Love: The Story of a Band Called Luxury; and The Jesus Music film. He also resurrected True Tunes as a popular podcast.

Thompson is the author of Raised by Wolves: The Story of Christian Rock and Roll; Jesus, Bread, and Chocolate: Crafting a Handmade Faith in a Mass Market World; and an upcoming novel, The Lost Dogs of East Nashville, which he’s self-publishing through a Kickstarter campaign.

We talk about that project below, along with the role of community in creative fields, alternative media, the challenges of finding your audience in a social media world, and more.

You’ve written a few books now, your latest being a novel. But you’re not publishing the traditional route this time. You’ve got a Kickstarter to self-publish—and also launch an indie publishing house. Tell us more.

Yes, after over two years working with an agent who had conversations with some major mainstream publishers and their Christian divisions, it became clear that no one seemed able—or at least willing—to imagine a pathway for a book that was deeply spiritual but not intended for exclusively “Christian” audiences.

The story also refuses to sit neatly inside of one of the existing genres that publishers use to describe books. It is not strictly a “romance” story, though it does get a bit romantic at times. It is not historical fiction in the strictest sense, though it does dip into that territory quite a bit. It is not mystery, horror, murder, or science fiction; so “genre” people don’t know what to make of it. But how would they describe The Commitments or That Thing You Do?

Today, publishers really have two jobs: editing and marketing. They help curate and edit books, working with authors to take their work from good to great. I have been an editor of one kind or another for over thirty years. I appreciate the value of that work.

For this story I hired a very accomplished fiction editor, Julee Schwarzburg, who works with many publishers, to be my editor. After eight years of work on the manuscript myself, and two proofing passes with other copyeditor friends, Julee and I spent over a year working together on it. I had never written fiction and needed her help to really take that step.

“The story also refuses to sit neatly inside of one of the existing genres that publishers use to describe books.”

—John J. Thompson

Her expertise was incredibly helpful, and the book shows it. She also encouraged me to pursue publication—though she could tell the path would be a challenge because the story didn’t fit neatly into any molds. As my agent got feedback from the major publishers one thing we heard was that they all recognized it was “ready to print.”

The other thing publishers do is marketing. This was where things fell apart for my agent and where he ultimately encouraged me to start my own imprint. My previous book, Jesus, Bread, and Chocolate, was published by Zondervan. They did active marketing for thirty days, and I’m grateful for it. But I did a sixty-date speaking tour, including two tours in Ireland. I built a full website, gave dozens of podcast interviews, created a whole line of ancillary merchandise items, and took chunks of chocolate to people’s homes! I personally sold over 3,000 copies of that book, and continue to ship them out to people who are just now discovering it nine years after it came out!

For Zondervan it is long dead. But the feedback I get from people is still remarkable. They just never found the right audience for it. Their system was not built for that. I went to pubs and homes and colleges and churches and schools and spoke—and people loved it.

I have been a songwriter and musician for most of my life, and in that capacity I know all about the benefits and drawbacks of genres and “markets.” Marketing is made much simpler if the product can be quickly described as this or that to a group predisposed to want this or that. But great stories—and great art—often refuses to sit inside of those boxes.

Now, I am not ready to describe what I have written as “great” just yet, but I am convinced that it is at least a good story that a much wider audience would enjoy. It would be a disservice to the work, and to the audience, to make certain changes to it so that it could fit into the “Christian book” box and appeal to that “market,” and if the mainstream publishers don’t see the appeal of a story about music and community and healing, then that’s their problem.

I am convinced that there are many out there who actually hunger for great, redemptive stories (and music) without the training wheels left on. A different way to approach this is to focus on identifying that audience. If we can find them. I believe that the audience is out there because I have interacted with them for over three decades.

And today I see more and more people—from teens to sixty-somethings—who resist the marketing aspects of the word “Christian” and are not even sure that it applies to them anymore. But when it comes to grappling with the deepest questions of life and love and sacrifice and friendship and redemption, they are all in. That’s who I want to serve. Because that’s who I am and have always been. And there are more authors and artists and filmmakers that need to reach that audience as well.

Where did the idea for the story come from?

The general idea came during a backpacking trip with some friends from our home group about ten years ago. We were hiking near Chattanooga on a mountain called Frozen Head and one evening I just started telling a story around the campfire. I think it was sparked by one of the guys asking me how I might convey the values and ideas of Jesus, Bread, and Chocolate in story form.

They say “write what you know” and I have been in and around the music world my whole life. So I started with a central problem: Can something, even something very good, get so big that it undermines its very reason for being? What if that thing had to do with music?

So my story focused on one man, who was diving into music as a way to find some kind of deeper healing. He was an older man living in East Nashville, so he had seen (and could talk about) all of the changes our community had seen over fifty years. He had lived through the devastating tornadoes in 1998 and then seen the resulting artistic renaissance and corresponding gentrification.

I started to weave in stories I knew from friends and family members about addiction and recovery and church pain and culture wars and disaffection. I think it helped that my oldest son was there. He was then about nineteen, but I had been telling him bedtime stories since he was born! This was basically a bedtime story for adults—most of whom were musicians. It went on for a long time, and everyone was into it.

The next day, as we were driving home, one of the guys asked me to continue the story in the car. I literally made up more and more pieces of plot and developed more characters off the top of my head for over three hours. They told me I had to turn this into a book, so I did. It took me over eight years, usually written in big chunks when I would lock myself away for a week in a cabin somewhere. But I also liked to take my laptop to various locations in East Nashville where the story was unfolding and compose it there.

This isn’t your first foray into indie publishing. As a teenager you launched True Tunes News. What appeals to you in the indie or alternative media scene?

I attended the Cornerstone Festival outside of Chicago when it debuted in 1984. I was not quite fourteen. That extremely progressive—even dangerous at times—combination of radical music, dynamic teaching, visual art, poetry, and visceral community absolutely enveloped me and transformed me. I determined that my life would be spent invested in propagating that kind of thing, encouraging those kinds of experiences for others, and creating that kind of art.

I started a band, I painted, I created weird clothes, I wrote stories. But the thing that really caught hold was True Tunes. Music, it seemed to me, was really an excuse for us all to gather. It definitely has certain inherent and intrinsic value to be sure. But it also provides a reason for us to meet up. We feel less alone. We talk and even argue together but in a fun way. We become a tribe. In many ways these culture-driven tribes have been incredibly harmful and toxic. But at Cornerstone it was incredible. My magazine was simply the publishing voice of what was happening every day in our little record store and concert venue in Wheaton, Illinois.

We refused to reduce things along “Christian/Secular” lines. We refused to play the “find a Christian version of X” game. Although we were kids—and I can’t say we fully pulled it off all the time—True Tunes was our attempt to find the audience that didn’t need the training wheels. We were much more about the U2, Dylan, Cockburn way of thinking about how faith and spirituality could and should inform art and culture.

My belief (and I think this was borne out) was that there was a much bigger audience for that than there was for the CCM stuff. Artists like The 77s, Daniel Amos, The Choir, Tonio K., and Vigilantes of Love deserved to be considered right alongside REM, Talking Heads, and Crowded House. I think we eventually saw that happen with groups like Sixpence None the Richer, Relient K, Switchfoot, P.O.D., Creed, and Evanescence.

When we launched TrueTunes.com in the late nineties, we had hundreds of thousands of unique visitors each day. Later I joined the staff at Cornerstone and helped them tell their stories as well. True Tunes was gone by 2000, but those groups all came through the nexus of Cornerstone and True Tunes, and I will always be proud of the small part I played in tilling that soil.

What are your thoughts on the importance in indie publishing of building a community?

I have many thoughts about this. It is cheaper and easier than ever for us to publish whatever we want. But because of this, everyone has their own website. Every episode of the True Tunes Podcast that I currently produce is significantly better than the magazine I used to publish. But the magazine reached exponentially more people. Even the first podcast I did, which was a combination show for Cornerstone and HM Magazine in 2005–07, would have over 50,000 downloads in the first day! That would be the No. 1 music podcast in the country if we had that right now.

It is so hard to cut through the “noise” to find our audience because so many people consume their own “content” through Facebook feeds, Instagram, and so on. The social media silos have tricked us into thinking we are connected, but we are not. But if we can inspire this audience to break out of some of those habits—even for just a few minutes a week—and open an email, listen to a podcast, or listen to a playlist, we can change a lot of things for both the creators and the consumers.

“It is so hard to cut through the ‘noise’ to find our audience because so many people consume their own ‘content’ through Facebook feeds, Instagram, and so on. The social media silos have tricked us into thinking we are connected, but we are not.”

—John J. Thompson

We may not have an actual festival like Cornerstone anymore, an event that 30,000 people drive to every summer. But we can create a virtual festival for vital, exciting, creative conversations and ideas. We just have to get out of our silos.

How did you approach building and sustaining a community for True Tunes in a pre-internet era and how does that compare to and differ from your approach today?

I think I touched on that a bit in the previous answer, but I will go a step farther here. With True Tunes we had layers. For many, maybe most, people their interaction with True Tunes was the magazine. So it was “virtual.” They had a physical thing, though. But they never met me in person. They could call a toll-free phone number and order CDs (and thousands did). Some of them got to talk to me on the phone; many talked to our staff members as the call volume grew. But that would be the extent of the community.

Some would come to Cornerstone and see us there. Some, though, came to the store. It was always fun to see people who made “the pilgrimage” to Wheaton. They would take pictures and just soak it all in. One night my wife Michelle and I were driving down Front Street to go to a movie and saw some kids sitting in front of the store when it was closed. She begged me not to stop, but I did. They didn’t know who I was, but I asked them who they were, and what they were doing.

“We just got here from Texas, and really wanted to see this place,” they said. “It kinda changed our life. But they’re closed. So we’re just sitting here soaking up the energy.”

It was Matt, Leigh, and Dale from Sixpence None The Richer. They had gotten to town to record their first record. Of course I introduced myself and let them in to see the store. I think they may have then joined us for our date night too. They got “discovered” when a guy heard their demo in our store. Those kinds of things—those moments—were so special.

We don’t have a physical space anymore. It’s all online. But I still make time to call people who reach out. I try to call one or two people each week. It means a lot to me, and I think to them. And we did just have a festival at Lipscomb called Wild Bison that had hints of that kind of community.

Today thousands of artists will release music online and no one will hear it. The same goes for authors and painters and photographers and screenwriters. I am now the director of music industry studies at Lipscomb. I want to not only help teach students how to navigate the existing levers of the industry but how to build the audience that will actually care about what they’re doing.

What are some challenges alternative media faces today that didn’t exist when you started True Tunes?

We have surrendered our audiences to the owners of the silos and we each have become so inundated with messages that we miss most of what is sent to us. So, even if I really want to know about your next book, you will have to pay Meta or Google a bunch of money to find me every time you release one. That is insane.

Now, there will always be an aspect of that when it comes to finding new readers or listeners. But it should not be this difficult to reach the people who already love what we are doing.

Publishers are often trusting Amazon to do this for them, and Amazon has developed some amazing tools to reach people (especially if they fit into nice buckets and boxes.) But Amazon takes such a crazy percentage of the money. It’s no better than when we had to sign punitive deals with publishers to get our books into bookstores.

When I started True Tunes I was focused on a niche of music, and I knew that when I published an issue of the magazine, or even later when I published an article online, lots of highly interested people would see it. The phone would start ringing. Today we have no guarantee.

With so much content available online—a lot of it very good—how do you think alternative media can cut through the noise and reach its intended audience?

I believe we need to solve this problem from both sides of the rope. On one side we need to develop better strategies for delivering our messages consistently. We need to be sure that it is not difficult to find us. I think that will involve continued participation in social media channels with an intention toward email lists (that people will actually want to open and read) and even occasional physical mail. But podcasts and playlists are a critical piece as well. We must be nimble with all of the tools.

However, on the other end of the rope I think we need to inspire our audience to change their behavior a bit as well. Some folks say you can’t do that. They must have never seen punk fans go way out of their way to get to one store to find cassettes of their favorite bands, or hip hop fans getting “mixtapes” to discover new artists.

When an audience can be inspired to care enough, they can be trained to behave in new and beneficial ways. We see glimmers of this with things like the continued growth of vinyl LP sales and people joining Patreon.

What can musicians teach writers about creativity?

I don’t see hard lines between the disciplines. I guess one thing is that the average musician puts out more volume. A musician has to release a lot more titles. Musicians are also often a lot better at branding. Some authors get that—and some have become kind of obnoxious about it—but branding can be very helpful and valuable.

You talk about appreciating “handmade music.” Tell us what you mean by that and how it translates to other forms of art and creative endeavor.

I believe that art is particularly important to us because it connects us to other people. We enter into their stories and experiences. Technology is almost always a part of that to some extent, but today we have taken it to such extremes that the human voice and story can be almost completely lost. All we hear is the machinery. Like junk food that gives us the calories without the nutrition, this hyper-processed music gives us the beat without the meat.

The same is true with AI-produced visual and written art. ChatGPT can crank out some pretty impressive “content” by reprocessing what computers have “learned” from other artists. But I still believe that handmade, human work will always win. It has to be honest. It has to be real. It has to be good. Good art is rare and special. Average art is now cheap and easy.

“Good art is rare and special. Average art is now cheap and easy.”

—John J. Thompson

I’m going to give you one of your own questions, one posed by the new novel: Can something good get so big that it undermines its very reason for being? Riff on that as you think about balancing artistic integrity and commercial success.

Obviously—spoiler alert—I think the answer is “yes!” We have taken on the values of industry far more than we realize. Bigger is almost always better. But in many significant ways bigger is the opposite of better. I cut to the chase and put the central question right at the very beginning of the novel.

Our “accidental band” has just played a benefit concert the night before. It was obviously a “success,” though you won’t get the details until later. In fact, they have generated so much “buzz” that they have been offered a spot at the famous Bonnaroo Festival. But the main character sits in a booth in his favorite little diner deeply troubled.

This “thing” just started as a way to make music with friends in the garage, and then the driveway for the neighbors. They had some really important and special times out there. But now they can’t do that. Too many people show up. So there is the question. What were they after in the first place? Was it a good idea?

Should they play the big show? Should they quit? Can you take something big and make it small again? And what about those deeper things you were working on—and through—that music had sparked? Can those things be protected “at scale”?

“Can you take something big and make it small again? And what about those deeper things you were working on—and through—that music had sparked? Can those things be protected ‘at scale’?”

—John J. Thompson

It’s one thing to pontificate about these things in a nonfiction way. What I have done in this story is to attempt to set up a quandary and then see how our heroes will navigate it. I also placed the whole thing in my own neighborhood, and East Nashville became a character as well. The whole thing kind of surprised even me in the end.

What are three books that taught you the most about artistic expression?

How Music Works by David Byrne

Bird by Bird by Anne Lamott

Faith Hope and Carnage by Nick Cave and Sean O’Hagan

Bonus:

World Within a Song by Jeff Tweedy

Miracle and Wonder (audible) Paul Simon

Soul Boom by Rainn Wilson

The Creative Act by Rick Rubin

Why Everything That Doesn’t Matter Matters So Much by Charlie Peacock and Andi Ashworth

What advice do you have for creatives who are interested in contributing to or starting their own alternative media platforms?

First start by creating a body of work. I’m personally frustrated with how difficult it has been to “build my platform” over the last decade for instance, but I am extremely proud of the work I have done on The True Tunes Podcast, the new songs I have written and recorded with The Wayside (“Not OK at All” and “Ghost in the Needle” are two of the best songs I think I have ever composed), and I am very happy with this novel, The Ballad of the Lost Dogs of East Nashville.

Do I wish I had 20 percent of the “platform” I had thirty years ago? Absolutely! But while I am doing responsible things to reach the appropriate audience, the continued creative work has made me a better artist. When new people do find me, there is a lot for them to discover.

Then, when and if you feel that it is time to create an alternative platform, look around to see who is doing something like what you are imagining. I look to people like Malcolm Gladwell. Then just start taking steps. Don’t think about the mountain. Think about the steps.

“Look around to see who is doing something like what you are imagining. . . . Just start taking steps. Don’t think about the mountain. Think about the steps.”

—John J. Thompson

Final question: You can invite any three authors for a lengthy meal. Neither time period nor language is an obstacle. Who do you pick, why, and how does the conversation go?

John Darnielle is one of my favorite all-round humans. His books have all been incredible. His recorded music with The Mountain Goats continues to inspire me to no end. That he is also able to speak credibly as a Christian, without creating “Christian” music or “Christian” books is so inspiring. I really hope to get him as a guest on the True Tunes Podcast at some point. I think we would have a great hang.

I would love to spend time with William Blake. I have no idea how it would go, of course, but I would love to know how his mind worked, how he approached day to day life, and where he fell on the question of “sacred” and “secular.” His work was hugely influential on me as a young artist, and I still find myself returning to it often.

I have always wanted to meet and hang out with Stephen King. His memoir On Writing was big for me, and the way he talks about his faith, again without succumbing to creating “Christian” books is big for me. I love his writing, his stories. I am especially drawn to the way he uses mental illness and addiction as a monster image. I wonder what he thinks about the idea of spiritual warfare.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Interested in John’s Kickstarter campaign for The Ballad of the Lost Dogs of East Nashville?

This is a great essay!

"Start by creating a body of work" ... I want to believe this is the challenge, not building the audience. Because I'll quit and have quit (many times) when I look at things related to the audience metrics.