A Scrambled Story and a Puzzle to Solve

Inside Vladimir Nabokov’s Head-Scratcher Classic ‘Pale Fire’

Imagine you write a story. Nothing long, just a few hundred words on a single piece of 8.5-by-11 inch paper, the kind you probably used in school if you are of a certain age.

Now, imagine you cut up this story into a dozen or so different and uneven pieces.

Then you rearrange this puzzle of a story back in a different order, delicately taping each piece back together. Then you take a Polaroid picture of it, stick it in an envelope, and mail it to a friend.

You have just described a Vladimir Nabokov novel.

Good Enough for Grandpa

I first stumbled on the work of Nabokov in the library of my grandfather. He was a grumpy old cuss, trudging around that big yellow rambling house of his, screaming at my grandmother whom he could never find when he needed her. He liked playing piano, painting like Picasso, and watching Matlock every afternoon.

But more than anything my grandfather loved reading. A retired journalist, he spent his days mostly reading and listening to the radio. He did not just read books, though; he read books about books: analyses, bibliographies, criticisms, and so on.

He was a man endlessly fascinated by words. On his unending shelves, I saw names I did not recognize as a child but would remember years later, well into adulthood, when I would get more serious about reading. Names like Hemingway, Dostoyevsky, and Nabokov.

Over the years, whenever I came across one of those names, I would make a point to pick up the book and give it a chance. If it was good enough for Grandpa, I reasoned, it was probably worth reading. The man knew books. Such was the case when I came across Lolita, a trade paperback version of Nabokov’s most famous novel, which had been sitting on our shelves for years. My wife had read it before, but I’d never touched it. This past winter, I did and loved it.

On the back of the copy I have there is a quote by John Updike about Nabokov, saying he writes prose the only way it should be written, which is “ecstatically.” This is an apt description of Lolita itself as it is a book to be blazed through, filled with writing that demands speed. Nabokov, I think, wants you to devour the book, not unlike the way in which his unreliable narrator Humbert Humbert attacks the innocence of his stepdaughter.

You want to keep flipping pages, one short chapter after another, to see what this villain does next. And so I did, resulting in finishing the book in less than a week.

Not What It Seems

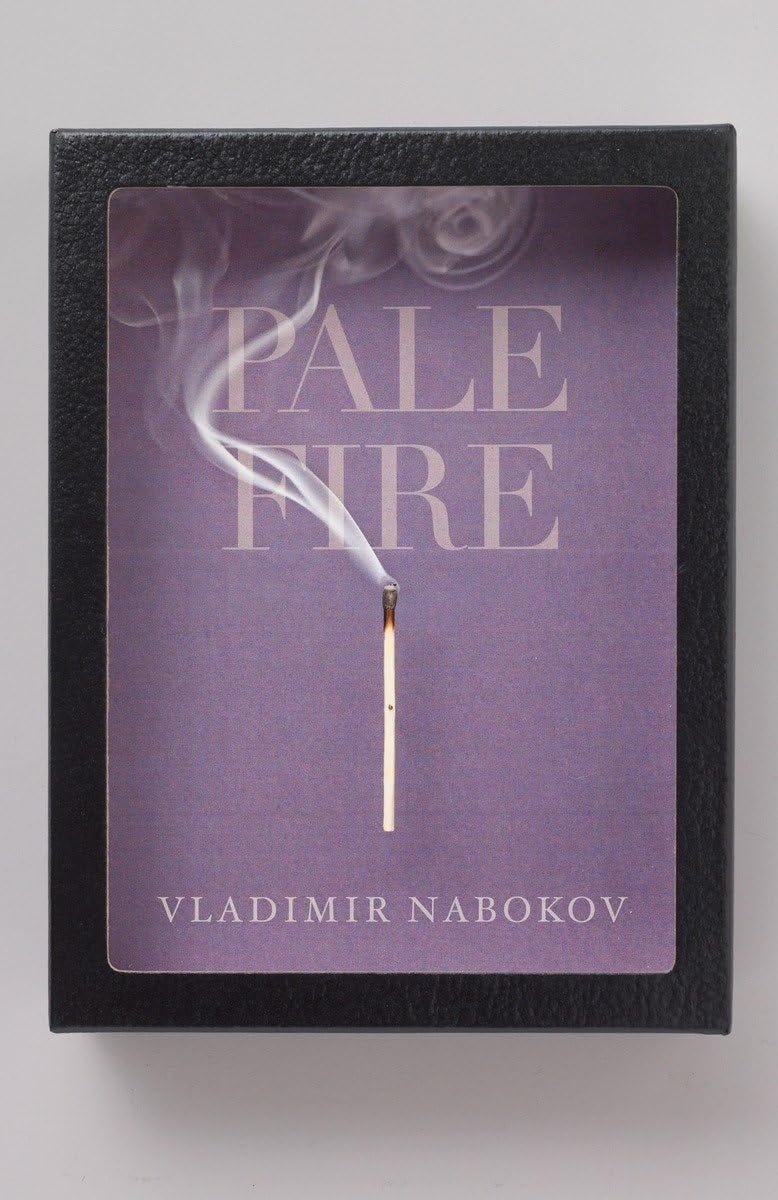

A month later, I came across another Nabokov novel, one I’d never heard of before, called Pale Fire, and bought it at an airport bookstore on my way home. The book, which I later learned is widely considered by many to be the author’s magnum opus, is not what it seems. It is, on the surface, a critique of a poem by another author; but soon you realize that something else is afoot.

Pale Fire is, in fact, a story told in four parts.

First comes a foreword written by the fictional author of the book you now hold in your hands—a college professor named Charles Kinbote—who is critiquing and evaluating the poem you are about to read, which is called “Pale Fire,” an obscure reference to a Shakespeare line.

The second part is the poem itself, written by the fictional author John Shade, a colleague of Kinbote’s at a fictional college located somewhere in Appalachia.

The third part of the book is the longest: Kinbote’s commentary on Shade’s poem, which he, our narrator, admits to editing and revising after his friend’s death, explaining in the foreword that he was able to wrest the rights to publish the poem from Shade’s widow.

Who is John Shade, and how did he die?

Why is Charles Kinbote the one who feels the need to explain exactly what happened?

We find out all this and more in the commentary, but first we take a detour into a story about a king from a faraway land called Zembla. Is Zembla a real place? Is Kinbote real? Can we believe any of this? Are we meant to suspend disbelief, or view all of this with suspicion? These are the questions Nabokov wants you to be asking as you read.

A Puzzle to Solve

This is a book I did not fully understand or appreciate until after page 100. Once I was in, though, I was hooked, studying each word in every section, paying close attention to the comments that seemed to be throwaways. I’d read enough Reddit threads and reviews at this point to know that it all belonged. It was all a part of the puzzle you, as the reader, are meant to solve.

Kinbote mentions at the beginning of the book that it would be best to buy two copies, one open to the commentary and the other to the poem itself so you can read them side by side. I opted for the single-copy approach and just flipped back and forth, remembering a comment from a reviewer: “With Nabokov, he is always winking at the reader.”

The commentary, and essentially the novel, ends with a climactic scene of Kinbote describing the death of John Shade, revealing the identity of the murderer, how it happened, and what it all means—probably the most interesting and beautiful finale to a novel I’ve ever read.

The book is funny, poignant, and mind-boggling. I couldn’t stop telling people about it once I’d finished it and immediately wanted to read it again. Little did I know, once I was finished with the story, the book was not over. The fourth and final section is a brief index: a glossary of people, places, and terms referenced throughout the book, along with reference numbers and lines.

Who is Charles Kinbote, and can we trust him? According to many readers, and to Nabokov himself, the answer lies in the index. At this point in the book, you have grown accustomed to flipping back and forth between poem and commentary, and this skill will serve you in the final few pages of the book, as it references some names that do not appear in the poem itself.

Sometimes with these discrepancies Nabokov is poking fun, trying to get a giggle out of the reader. Other times, he is calling your attention to an all-important detail that just may unlock everything. But I’ve already said too much and given you far too many clues than I had before beginning this almost choose-your-own-adventure story.

Arranging the Pieces

Pale Fire is not Lolita. It’s not a quick or easy read, and it demands a scrupulous focus. This is a book that demands a certain pacing of the reader, a studiousness. You need to slow down as you read and really consider what every line, play on words, and seemingly non-sequitur remark might mean.

This is a book that will, at once, make the reader feel stupid for what they don’t understand and smart for what they do. At least, it did me. But mostly it is a ride, one that sticks with you long after you finish, offering much to consider on a second or third reading, which may have been the author’s intention all along.

The point of a puzzle, Nabokov suggests with Pale Fire, is not whether you solve it but all the various ways in which the pieces could be arranged, much like how Kinbote treats Shade’s poem. Much like how we, perhaps, treat our own lives. So, what does it all mean? How do the pieces fit? Good questions, and perhaps only ones we can answer ourselves.

Just don’t forget to read the index.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

I 100% agree with your recommendation! "Pale Fire" was my first Nabokov novel (recommended by Ted Gioia, AKA "The Honest Broker"), and it made me an official Nabokov fan. I could probably write a whole wall of text praising the book, but instead I'll just highlight how amazing it was that Nabokov wrote a whole 1000-line narrative poem in a (to him) foreign language.

I was first introduced to Nabokov by the band The Police in their 1980 song "Don't Stand So Close To Me." In the last 2 lines of the third verse, Sting sings "It's no use, he sees her, he starts to shake and cough, just like the old man in that book by Nabokov." I didn't read "that book," AKA "Lolita," until more than a decade after first hearing "Don't Stand So Close To Me," but that was all right because I could appreciate the book much better then than I could 10+ years ago (and "Lolita" isn't the first or the last book that Sting inspired me to read).

Jeff, you have written a wonderful and enjoyable post. Thank you.