The Future Wants to Know: Where’s My Flying Car?

Failure of Imagination or Nerve? Reviewing ‘Where Is My Flying Car?’ by J. Storrs Hall

When George Jetson first flew into view in 1962 he did so in a flying car, zipping the kids to school and himself to work. Only one detail fails the futuristic image: his wife Jane taking his wallet as she splits for the shopping center. They use cash in 2062? They have shopping centers?

We already possess some of the inventions pictured in The Jetsons (for instance, flatscreen monitors). But a gravity-defying family car is not among them. Venture capitalist Peter Thiel is famous for many things, including his 2011 quip: “We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.” Twitter has since doubled its character count, but we not much closer to flying cars than when George Jetson first aired six decades ago.

Computer scientist J. Storrs Hall finds that unacceptable.

Wonders of the Future

Sci-fi authors and futurists told us we could expect all sorts of wonders. Some have come true. Pocket telephony, video phones for reading and commerce, a “global library”—cellphones and the internet took care of these and more. We’re not even impressed by them any longer.

We’re close to another prediction as well, self-driving cars, but those vehicles are resolutely on the ground. Why?

The technological advancements in the early twentieth century are astonishing. The Wright Brothers pioneered mechanized flight in 1903. Four decades later Chuck Yeager was breaking the sound barrier. Two decades after that Apollo astronauts went to the moon and back. Meanwhile, air travel by plane became boringly routine for middle-class Americans.

Based on that trajectory, individual flying machines seem as inevitable as the writers for The Jetsons imagined: Of course we’ll be scooting through the air in flying cars! Like Doc Brown told Marty McFly, “Where we’re going, we don’t need roads.” And Back to the Future was far more ambitious than The Jetsons; Doc’s modified DeLorean flies in 2015, while Marty floats atop a hoverboard.

Personal conveyance is airborne! Except it’s not. The futurists got it wrong.

In his book, Where Is My Flying Car? Hall points to a dual observation made by inventor, futurist, and sci-fi author Arthur C. Clarke in his book, Profiles of the Future—published, coincidentally, the same year The Jetsons first aired, 1962. “Clarke listed two major forms of failure risked by technological prognosticators,” says Hall: “the ‘Failure of Nerve’ and the ‘Failure of the Imagination.’”

The latter happens when people assume proposed innovations are impossible; an idea seems too farfetched, and they can’t imagine a path from here to there. The Failure of Nerve, on the other hand, “applies when the facts are known: The science is there, the engineering understood, the pathway clear, and only the details remain to be worked out.”

Hall’s book demonstrates flying cars belong to the Failure of Nerve camp. The necessary technology either exists or could be developed, but various forces have erected barriers to market entry that have substantively blocked any potential progress.

The Machiavelli Effect

There is a general reason for this Failure of Nerve and a specific one. First, the general, which Hall calls the Machiavelli Effect from a perceptive quote in The Prince:

There is nothing more difficult to take in hand, more perilous to conduct, or more uncertain in its success, than to take the lead in the introduction of a new order of things; because the innovator has for enemies all those who have done well under the old conditions, and lukewarm defenders in those who may do well under the new.

Speculative innovations might fail, so peripheral supporters tend to adopt a wait-and-see posture. And then there’s the active opposition, formed of those whose status or values would suffer should the innovation take root. That takes us to the specific reason: the combined effect of lawyers, regulators, and environmental activists.

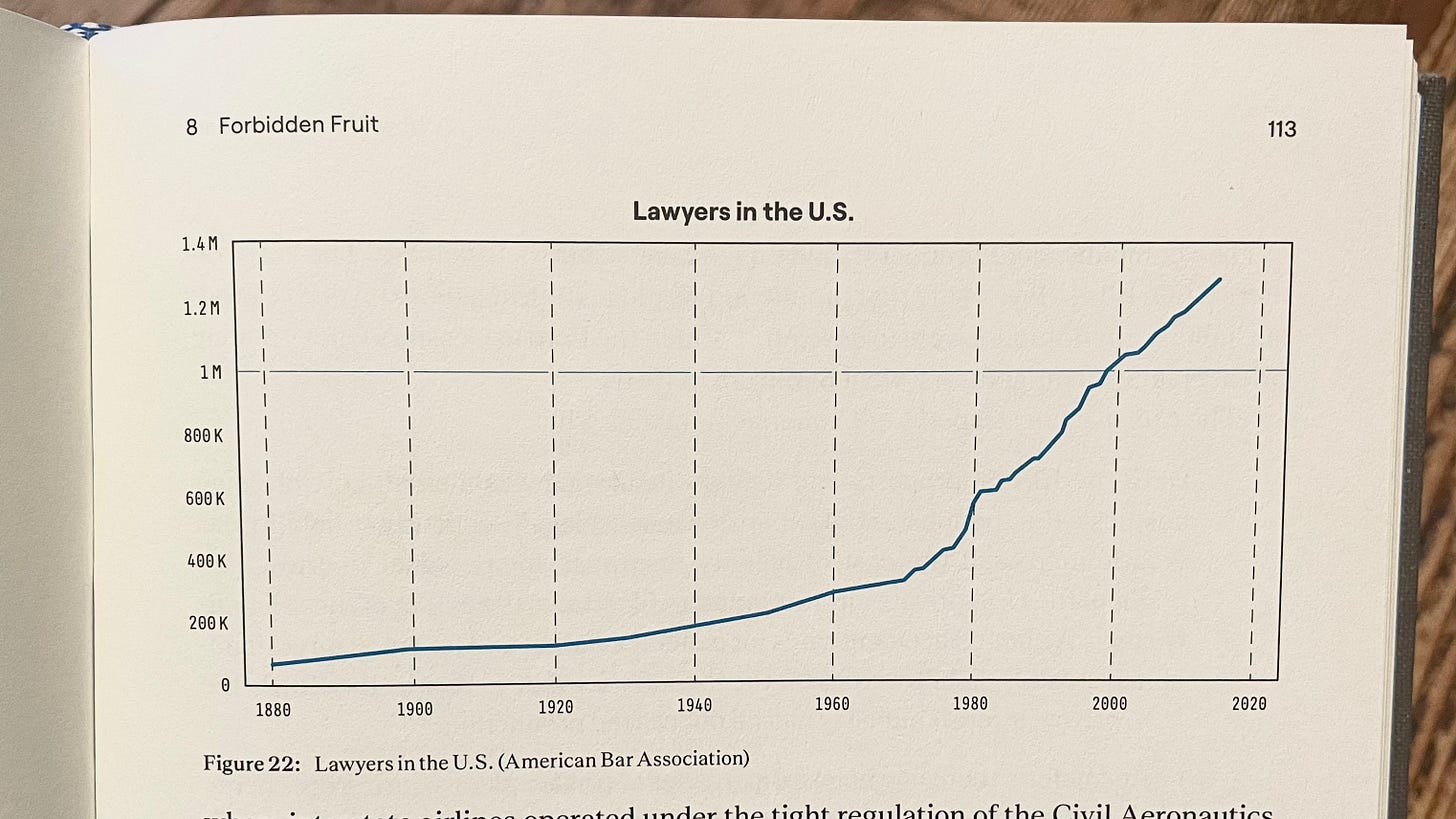

Consider private planes. The product-liability industry ballooned in the 1970s and law schools flooded the U.S. with doctors of jurisprudence looking for a piece of the action. “This led,” says Hall, “to a collapse of the general aviation industry.” It took private airplane manufacturer Piper out of business and almost grounded Cessna. The impact lives on in the cost. “A new Cessna Skyhawk cost $25,000 in 1980,” he says, “and over $300,000 today.” Can’t blame inflation for that one.

Hall’s explanation encompasses far more, including a sophisticated analysis of power requirements for personal aviation devices, an economic analysis of travel theory and how much value flying cars might provide compared to the costs of production, even practical considerations, such as: do you want the average driver on the road today flying a car tomorrow?

With Hall’s detailed treatment, flying cars emerge as feasible on every front—and not simply based on armchair theory and napkin calculations. In the research process for the book, Hall went so far as to get his pilot’s license and buy a personal plane.

The Bigger Picture

Of course, there are a number of challenges in equipping personal flying vehicles, not least powering them cost effectively. But the Machiavelli Effect comes into play here as well, shifting the flight path of Hall’s book beyond a curious meditation about airborne conveyance to a wider exploration of technophobia and economic vitality. This, I think, is the real value of the book for anyone who isn’t personally excited about zipping through the air for lunch in another city.

What kind of future do we want, one marked by dynamism or stasis and stagnation? We often know the way to improve our current situation. For all our fretting about it, nuclear power is, for instance, cheaper, safer, cleaner, and more scalable than any alternatives. And yet rather than invest the resources to improve plant design, nations are mostly busy adding coal-burning capacity, while decorating their terrain with difficult-to-scale wind and solar. All the while, we require not only more power but more efficient power as global population grows.

Retaining coal over nuclear represents a Failure of Nerve and, as Hall points out, it’s not the only one. The case of the flying car serves as a parable about threats to technological advancement, environmental health, and human flourishing and longevity.

If George Jetson were forty years old when he first flew across our television screens—which seems about right given the age of his kids—he would have been born in 2022. At our current pace of development, there’s no way his flying car will be ready for the morning commute. I wonder what else he’ll miss.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this review, please share it with a friend.

More remarkable reading is on its way. Subscribe so you don’t miss out!