I Apologize in Advance: The ‘B’ Word

How Can a Word Be this Flexible? Let Me Count the Ways

I was reading J.D. Salinger’s Franny and Zooey last weekend and encountered a use of the B word I’d never seen. At least, I didn’t remember ever seeing it. Before I share it, a warning: This is either completely gauche or utterly fascinating, possibly both. I apologize in advance.

As the scene unfolds, the dapper young Lane anticipates a delightful weekend with his girlfriend Franny, whom he hasn’t seen in weeks. But she’s clearly disturbed after stepping off the train and proceeds to make sarcastic, alienating remarks throughout lunch. No fun. Lane worries Franny is going to “bitch up the whole weekend.”

Yep, that’s right! Bitch as a verb meaning to mess up, screw up, or ruin.

Honestly, I was thrilled to come across this usage, because keeping track of the curious jobs words find to do in sentences has long been an almost subconscious linguistic hobby of mine.

How it normally works: I hear an odd usage and then somewhere in that soft spot between my eyes and my ears a little man jumps up and retrieves it like a baseball struck deep into centerfield and high over the fence. Up goes the glove, and an eager fan suddenly has a new trophy to display on the mantelpiece at home.

I say it’s almost subconscious because for a moment I do take note of it. But then like that fan who moves on to other interests in life my trophies usually gather dust, far from the gaze and scrutiny of my attentive mind, rolling around in my head under what neuroscientists would call the P300 waves.

But then. . .

I read something like “bitch up the whole weekend,” snatch another homer out of the sky, and install it in the usual place, only to gradually recall all the other curios from prior adventures. The P300 wave crests, and I float away on currents of remembrance and creative reassembly. Man, I think, you can use that word for practically anything!

And it’s true: Bitch can do it all. Let’s start with adjectival bitch.

California Dreamin’

I can still recall sitting in my Uncle Ned’s Volkswagen van as a ten or eleven-year-old when he placed a hat on his head, turned to me, and said, “What do you think of this hat? Bitchin, huh?”

Adjectival bitch! I grew up in California so I’d guess I’d heard it before, but that was the first time it really registered. Like any kid, I grew up knowing how to get close to forbidden words without stepping over the line. Thus I was well aware that bitch formally meant a female dog. I was also aware no one really used it that way, though I loved watching the original All Creatures Great and Small and heard Siegfried Farnon toss it around all the time.

Still, when we kids hit the playground, we’d insult each other by saying, “You son of a female dog.” Bitch was going too far. But then here was my uncle throwing out adjectival bitch like it was nothing. I knew he wasn’t being rude; I couldn’t have communicated this at the time, but he was being ironic and thus being funny; that’s my Uncle Ned. What I did realize then was that adjectival bitch was somehow different than the original noun form—especially its pejorative use.

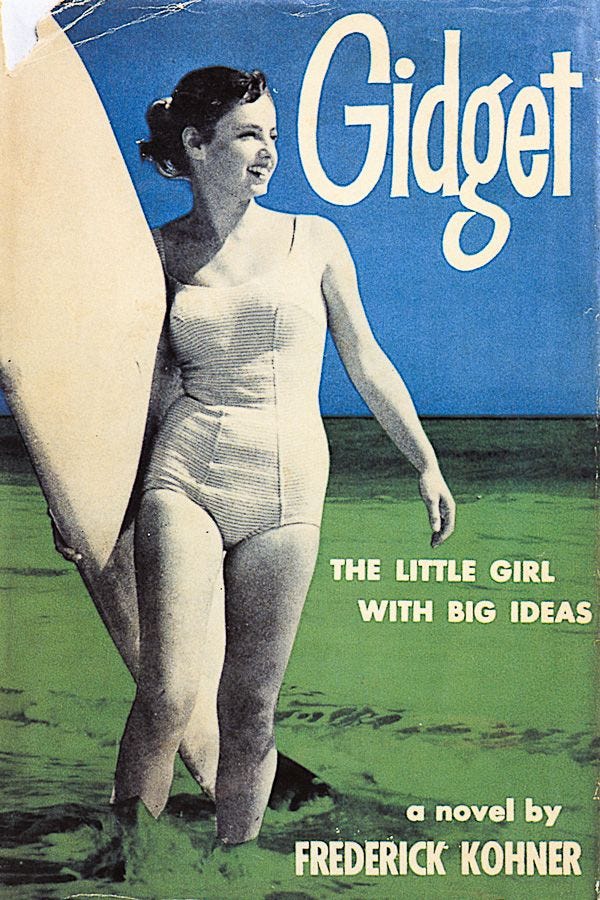

Credit California. Adjectival bitch, particularly its positive use, goes back to surfer culture. One of the first recorded uses is from Frederick Kohner’s 1957 novel, Gidget, which portrays Golden State surf culture in the fifties. “It was a bitchen day,” remarks the teenage narrator Franzie in one of (by my count) nineteen instances. The word, spelled with an e, meant nothing more than superb or excellent, the furthest thing from off-color.

Syntactically, bitchin can be used attributively, as in “bitchin day” or predicatively, as in “Dude, the weather was bitchin!”

Skate culture, heavily influenced by surf culture, picked up the word too, but by the time I was skating as a teen in the late 1980s, it was old-fashioned. It was old-fashioned when Uncle Ned used it, too. After all, he was joking. So were the screenwriters who had Pee-wee Herman resurrect it in 1987 for Back to the Beach, a retro showcase for Annette Funicello, who had starred in a string of surfer movies back in the sixties. As Pee-wee sings (I use the verb generously) “Surfin’ Bird,” he peppers it with surfer slang like gnarly, tubular, and bitchin.

But—and this probably won’t surprise anyone—bitchin didn’t start as a compliment. American GIs used the word to refer to something big or formidable: “a bitching hard job” or “a bitching storm.” During WWII an adjacent compound noun popped up, bitch kitty. “Bitch kitty of a plane,” a pilot might say, meaning it’s dangerous.

Bitchy represents another adjectival form of the word, one more clearly negative and possibly off-color, such as “a bitchy remark.” Functionally, bitchy expresses irritability or spitefulness, and it can be used attributively or predicatively, as well: “bitchy remark,” “don’t get bitchy about it.”

What’s interesting about these two contrasting forms of adjectival bitch is the positive/negative split. Bitchin plays a game linguists call semantic inversion, when a word adopts a meaning roughly opposite an earlier meaning. You can almost imagine it happening on the surf. A big or formidable wave is bitching in the earlier, American GI sense. But for surfers that’s desirable. So “bitchin wave” (note the dropped g) becomes a positive statement, and then it simply abstracts to a positive adjective across the board.

Bitchin hat, right?

Negative Waves

Many common uses of bitch are negative, which is why I was wary about its use as a kid and remain circumspect about using it today, despite a far more playful attitude.

The noun goes back to the Old English bicce or bicge, which scholars tell us comes from the Proto-Germanic bikjǭ, all referring to a female dog, perhaps the least interesting use and meaning of the word. That didn’t last. By the late Middle Ages and early modern period, the word had moved into derogatory or disparaging territory. That’s pejoration—a linguistic process where words attract negative meanings, like, well, a bitch in heat attracting neighboring dogs. Which might even point to how the word began taking on negative connotations.

In Nine Nasty Words, John McWhorter provides several examples from the period of the term being applied to women with restless sexual appetites. As a result, the word jumps species and even categories; a simple description becomes an insult, a slur. Unfortunately, that’s where most of our minds park when we think of the word. We might allow for a little stretch like son of a bitch, which simply extends the gendered insult to include men by insulting their mothers. But we forget the rest of the uses of the word that were creeping into the language even way back then—in fact, even before the early modern period.

Sticking with negative uses, McWhorter points to “bitched” being used to mean cursed: “bitched bones,” as Chaucer would have it, meaning cursed dice. There’s yet another adjectival bitch, derived from bitch as a verb, to bitch, meaning to jinx something. So, for instance, “He bitched the dice before rolling them” (verb), gives us “those are bitched dice” (adjective). Incidentally, this is remarkably close to Salinger’s use of bitch as a verb in Franny and Zooey, to wreck or ruin.

When a noun starts playing the verb in a sentence, particularly without any change to its spelling, linguists call that conversion or zero derivation. You can verb pretty much any noun; I just did it with verb. We do it all the time when we text a friend or Google a restaurant.

As a verb, bitch usually conveys the negative connotations it picked up as a noun. When we use it, we mean to gripe or complain: “He bitched about the new schedule.” “Quit bitching and do your homework.” It plays a similar game as an adverb, bitchily, though this is pretty rare in real-world use. In writerly land we’re typically averse to adverbs by training. “Use a stronger verb,” we’re told. But you can imagine a sentence like “he responded, bitchily” or even “the motor screeched, bitchily.”

Going from noun to verb to adverb reminds us of an observation McWhorter has practically build his career on, words won’t stay put. They wiggle and jump. So the noun bitch not only goes from mere descriptor to slur, it can also broaden again to mean any irritant or nuisance: “Life’s a bitch” (a trial), “The bitch wouldn’t budge” (a stuck bolt), or “The bitch won’t move” (an immobile car). And revisiting our earlier example, you can see how metaphorical use and inversion can turn the verbal usage, as in “that wave was bitching” (the wave was behaving as if it were aggressively complaining), into a positive adjective: “that wave was bitchin!”

But it doesn’t stop there. Just as the surfing subculture inverted the negative meaning of bitchin, so the feminist subculture inverted the pejorative use of bitch.

Positive Spin

When Meredith Brooks’s anthemic song, “Bitch,” hit the airwaves in 1997, she reappropriated the slur as a compliment.

I’m a bitch,

I’m a lover,

I’m a child,

I’m a mother,

I’m a sinner,

I’m a saint,

and I do not feel ashamed.

Gay subculture adopted the word the same way, so in both female-coded and queer conversations bitch (sometimes spelled betch) is a way of saying friend or expressing affection.

At the office, we once had a crotchety tech in a muscle shirt bring his dog when working on some of our equipment. Several of my colleagues expressed delight in his little friend, and at one point he grabbed his dog by the face, put his kisser right up to next to his snout, and cootchie-cooed, “Yes, the bitches love me,” playing with both the original term and the inverted pejorative. A little out of place at work but clever.

A Mostly Neutral Note

As McWhorter points out bitch can also function like a pronoun, especially in Black English. “Bitch set me up!” said DC Mayor Marion Barry when nabbed using crack with a woman. “He was,” says McWhorter, “saying ‘She set me up!’” That is, bitch was standing in for a third-person pronoun. McWhorter also mentions Cardi B using it as a first-person pronoun, “I ain’t gonna front,” she said. “A bitch is scared”—that is, “I’m scared.”

And just like bitch went from a slur for a person to a reference for a nuisance, bitch can play the placeholder in other instances, working as a deictic surrogate—that is, a pragmatic term whose use depends entirely on context, like this or that. In this usage, bitch stands in for practically any thing, place, or situation:

“Bitch won’t budge.” As mentioned before, a stuck bolt, door, or drawer.

“That bitch is loud!” A neighbor’s stereo, an old refrigerator, or malfunctioning fan.

“You just have to ride the bitch out.” A storm, a difficult conversation, a terrible Monday.

“Bitch caught fire.” An engine, a cellphone battery, a frying pan.

“Let’s get in this bitch and go.” A car, boat, plane, or other method of conveyance.

“We gotta fix this bitch.” A broken-down car, glitchy spreadsheet, or anything not working properly.

“Hold the bitch steady.” A ladder, a camera rig, a firehose.

“Bitch disappeared.” Your missing AirPod, left sock, or last version of a computer file.

Then there’s flip a bitch, California slang for making a U-turn. Exactly how it means that is up to interpretation. Bitch could be a deictic surrogate for vehicle with flip referring to turning the bitch around. Or bitch could refer to the maneuver itself with flip serving to emphasize the action. In all these cases, bitch maintains a mostly neutral, context-dependent meaning.

Finally, at least for this piece, there’s bitch’s role as an intensifier. Here, it pretends to be a noun but it’s really an adverb. We might imagine someone say they were “working like a son of a bitch,” that kicking the doorframe “hurt like a bitch,” or—in my favorite case—someone even expressing the vastness of their love with the term. In the Coen Brothers’ movie Intolerable Cruelty, Billy Bob Thornton crumples up his prenup, dips it in barbecue sauce, and eats it, exclaiming to Catherine Zeta-Jones, “I love you like a son of a bitch!”

What Have We Learned, Class?

My dad is an English teacher. There’s a part of me that wishes I could teach English just to have a lecture in which I demonstrated not only all the parts of speech, but also all the linguistic concepts, exemplified by bitch. It’s a word that can describe, insult, empower, amuse, intensify, or just fill in the blank. It’s one of the most context-sensitive words in the language. Playful in one mouth, vicious in another, its syntactical flexibility is matched only by its social complexity.

For laughs, here’s a paragraph that tours all the ground we covered above, except the original meaning of the word:

Bitch, I bitched about that bitchy project extra bitchily, until this bitch bitched the deadline so bad I had to restart the whole bitch from scratch. And that stubborn old bitch? Bitch still won’t move. Not bitchin. In fact, it’s totally bitched. Meanwhile, this bitch right here? Just trying to keep it together. Luckily, my best bitches showed up with coffee and croissants and said, “Let’s fix this bitch and bounce.”

No dogs in sight! But if that paragraph is a little unclear, here’s a breakdown so you can see all the uses in action.

Bitch (vocative noun): direct address, establishing tone and attitude.

bitched (verb: to complain): expresses frustration.

bitchy (adjective: pejorative): describing the project’s difficult or irritating nature.

bitchily (adverb): describes the manner in which the speaker complained.

this bitch (placeholder noun/deictic surrogate): refers to the situation or system at hand.

bitched the deadline (verb): to wreck or sabotage the timeline.

the whole bitch (placeholder noun, intensifier): amplifies the scale of the problem.

that stubborn old bitch (noun: insult/irritant): metaphorically describing a system or uncooperative object.

Bitch still won’t move (noun as subject, intensifier): reinforcing frustration; possibly a personified object or system.

Not bitchin (adjective: slang-positive, here used ironically): contrast with previous usage.

totally bitched (historical participial adjective: cursed or jinxed): references the “bitched dice” lineage.

this bitch right here (noun as first-person pronoun): self-referential, stylistic echo of Black English usage.

my best bitches (reclaimed affectionate noun): queer-coded, playful camaraderie.

this bitch (placeholder noun again): returning to the central “thing” that needs fixing.

Got that? Bitch, please.

Thanks for reading! Please hit the ❤️ below and share this post with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

It's what I love about you... Gidget, Pee-wee Herman, and event-related potentials (P300 wave) in the same article. You're a super genius, polymath, and I'm here for it!

This was fun, or shall I say, bitchin?