The Humanities Are Not Dead, Just Adjusting

Rumors of Their Demise Miss Subtler Realities and Realignments

In his 1704 fantasy, The Battle of the Books, Jonathan Swift imagined a fight in a library. The opponents? New books vied with old books for supremacy, the classics against newfangled philosophy and science. In an updated version of the tale, books—of any age—would vie against test tubes, algorithms, servos, and pivot tables. And if a recent New Yorker article by Nathan Heller is any indication, the books would find themselves bloodied and bruised.

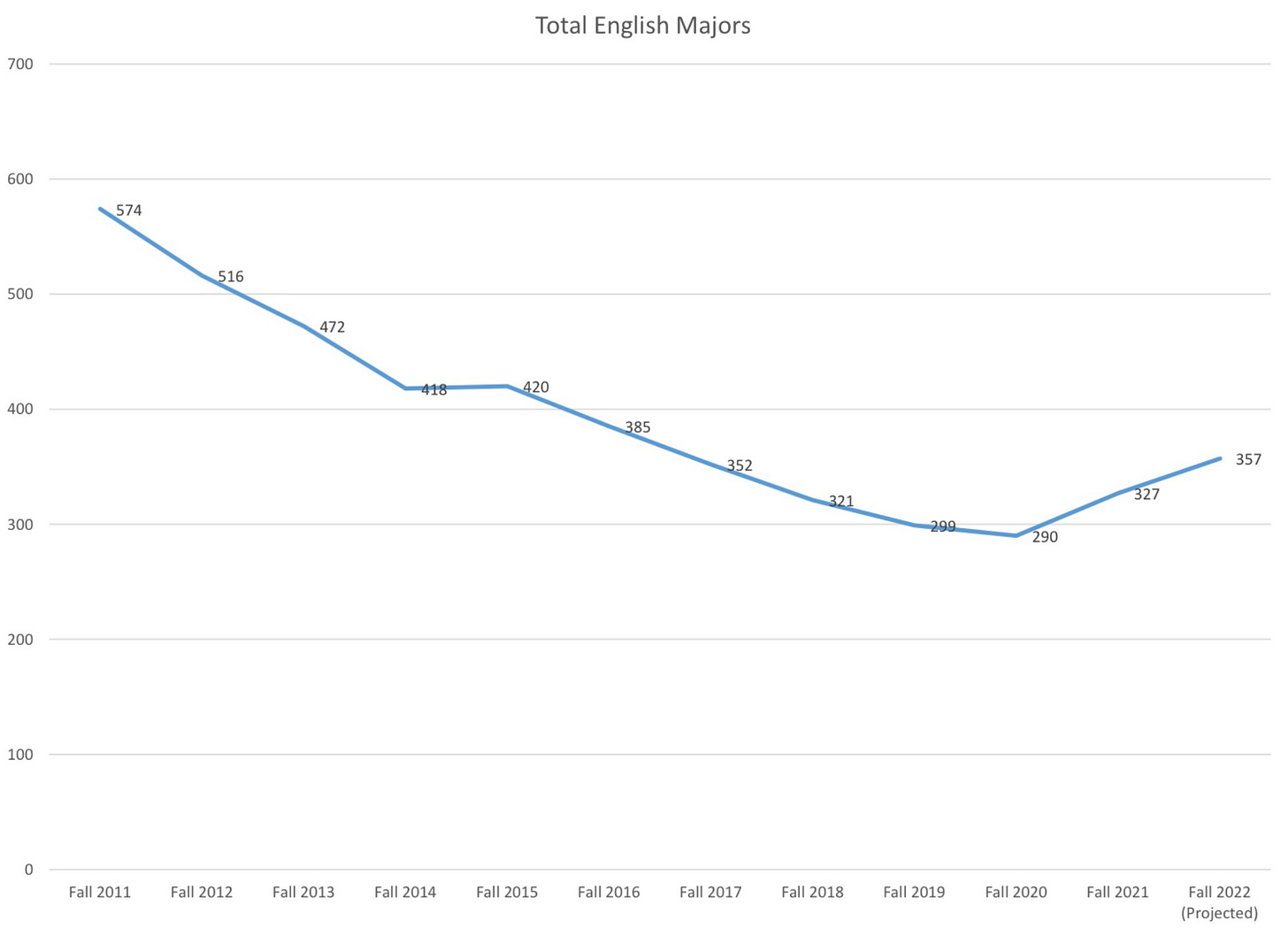

“Humanities enrollment in the United States has declined over all by seventeen per cent,” says Heller, citing data collected by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences from 2012 to 2020. The fate of the English degree comes in for special lamentation. In the last fifteen years, Harvard’s English enrollment has, for instance, shrunk by 75 percent or so. “We feel we’re on the Titanic,” one professor told Heller.

The simplest explanation for the slide in the humanities, particularly English, is marketability. If you’re looking for gainful employment with any hope of chipping away student debt, a degree in science, technology, engineering, or mathematics might make more sense. As the economy grows steadily in STEM-aligned directions, spending time with The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy could seem beside the point. Or maybe not.

More to the Story

Despite the apparent trends, the humanities—even English—are thriving in some sectors. Grove City College English professor Jeffery Bilbro notes that with fewer than half the students of Harvard, Grove City nonetheless has twice the English students.

Hollis Robbins, dean of humanities at the University of Utah, had a similar response to Heller’s article. After dropping to a low point in 2020, University of Utah English majors hit the floor with a bounce. “Our enrollment numbers are up,” she tweeted. “The English major is more popular now than it has been in years!”

“What becomes clear after the pandemic is that English majors have bounced back big time,” Robbins told me, “largely because of medieval and Middle English texts, because of video games.” Video games? Sounds STEMy: an important reminder that multiple paths might exist to acquire the necessary skills and knowledge for one’s desired field. An oblique path is superior for some.

Beyond that, says Robbins, focusing on English enrollments misses a larger shift toward specialization. “A histomap of our department/program structure . . . shows where students might have gone to major instead of ‘English’ even as they are still doing ‘literature’ (like World Languages and Cultures, Latin American Studies, Writing and Rhetoric, or Religious Studies),” she says.

When I think of the comparison between Harvard and Grove City College, it’s not hard to imagine students pursuing humanities are doing so in more affordable schools. Perhaps the Ivy League premium isn’t worth the tradeoff in the minds of economical students. And the same is true for more specialized majors; students are choosing—and in some cases creating—paths that more uniquely suit their needs.

Humanities Stage a Comeback

The positive trends at the University of Utah aren’t isolated. Last fall UC Berkeley reported that enrollment in humanities were up. “The number of individuals who apply to Berkeley to become first-year students majoring in the Division of Arts and Humanities is up 43.2% compared to five years ago,” said Sarah Fullerton in the Berkeley News, “and up 73% in comparison with 10 years ago.”

What’s more, said Fullerton, “Many interdisciplinary departments that teach creative problem-solving—including art practice, comparative literature, philosophy, music, history of art, and film and media—saw their highest applicant year in a decade.”

This uptick appears to be part of a wider movement. While humanities at Arizona State University, particularly English, elicit heavy handwringing in Heller’s article, noting massive falloffs between 2012 and 2020, ASU has since “seen a rise in students declaring humanities majors,” according to a report in Axios. And the same is true for other schools. “The University of Arizona’s College of Humanities has seen,” reports Axios, “a 33% increase in student majors since 2016.” The University of Arizona has gone so far as to STEMify their program with an “applied humanities” department, currently its fastest growing.

Of course, any humanities degree can be applied—to all sorts of fields—if the student is creative enough. My bachelors is in communications. After some application in legislative politics and opinion journalism, I became a developmental editor and book publishing executive, then a content developer for a small-business coaching company, Full Focus. I currently lead a team of content creators, product developers, and executive coaches.

To read widely is to think broadly. I can’t tell you how often I pluck a spot-on argument or anecdote from Stoic philosophy, Greek myth, Hebrew scripture, or medieval history. Point your nose in the direction of Armand D’Angour’s collection of ancient innovation texts; they smell contemporary for a reason. As William Faulkner said in Requiem for a Nun, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” It’s still speaking.

Ongoing Relevance

Humans have been doing formal philosophy for thousands of years now; you can’t have computers without Aristotle. Written myth, literature, and song go back further. Oral versions of the same stand behind those; same with the visual arts. All of these humane pursuits contributed to our cultural evolution, and we cannot fully understand our culture today—nor address its concerns—without attending to that development to one degree or another.

I don’t want to oversell the humanities. They’re not a toolkit for every problem. But they are a toolkit for many. Maybe more importantly, they’re tools that can help us better wield and refine our modern technologies. STEM needs the humanities. And it seems students still recognize the fact, as do administrators and professors who help connect the dots and make applications others might miss.

Thank you for reading! Please share Miller’s Book Review 📚 with a friend.

If you’re not a subscriber, take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!