How Long Should This Sentence Be? Bad Question

Pardon Me While I Lodge a Complaint

People write short these days. We’re told to write short. Make it punchy. Make it pop! Semicolons, conjunctions? Screw ’em. A sentence should be short enough to make a writer sweat trying to tighten, crimp, and cram it all in before the window closes and the lights go out.

I’ve been a professional editor since 1998, and if there’s one thing I’ve learned to loathe over the last three decades it’s writing advice. Stab me in the face. There are thousands of books about writing—I own more than a few—and endless websites proffering tips and tricks. Caveat emptor. Most are lousy and should be heeded with the same fervor as a bad sermon.

Over the last however many years, most of these Oracles of the Right Way to Write have converged on the sacred dictum that sentences should be attenuated, stubby things—only so long, circumscribed by rigorous recommended word counts. Fifteen words is a pretty typical average (see here). The reason? Short sentences are supposedly easier to process. Maybe. But that’s like saying every meal should be a smoothie since it’s easier to chew.

Also, as you’ll see, I don’t think it’s strictly true.

To be fair, this advice comes from somewhere real. Screens encourage skimming, journalism craves speed, and accessibility matters. The advice isn’t malicious, but it is mindless—a useful technique mistaken for a universal law.

The point of a sentence is to communicate a thought—that’s basically what a sentence is, a complete thought. But if that’s the goal, then length is secondary to the thought itself, to whatever the author is actually trying to communicate. And unless you’re reading an instruction manual or a police report, what the writer wants usually goes beyond merely conveying information and includes an attempt to evoke a feeling, an experience, in the reading. The best stylists do that, which is why nobody bitches about the length or complexity of George Eliot’s sentences in Middlemarch; they just get swept away by the magic she conjures.

Who should we blame for this militant adherence to the minimal? The writer Ed Simon points to the proliferation of style guides whose advice people cling to like papal pronouncements. Those yammering ex cathedra include George Orwell, William Zinsser, and of course William Strunk and E.B. White, who collectively advise that writers expurgate anything extraneous from their sentences. “A sentence should contain no unnecessary words,” inveigh Strunk and White with authority once reserved for the twelve apostles. But how do you define unnecessary?

“For the authors of such style guides, good composition is an exercise in the literal, the straightforward, the utilitarian,” says Simon. And we can all groan with the anticipation of reading prose as exciting as boneless, skinless, unadorned, microwaved chicken breast. Never mind that White didn’t even follow his own advice; Simon mentions a sentence in his beloved children’s classic Stuart Little that runs an ambitious 107 words.

Some of this nonsense comes down to muddling description and prescription. Hemingway wrote short and suggested the same; Hemingway was successful; ergo, everyone should write short and parrot the principle. But that’s only true if you’re happy remaining an unserious person. Sentence length is far more art than science—and definitely not a game of hamfisted rules no more sophisticated than counting on your fingers.

Consider the alternative tradition. Simon rattles off a string of writers who violate everything we’re told to do: Cervantes, Swift, Joyce, Woolf, Nabokov, Rushdie, Atwood, Zadie Smith. Unreadable trash, right? They all have sentences that trespass 100-plus words with no sign of repentance.

Some authors revel in transgression. William Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom! boasts a sentence of 1,288 words. Jonathan Coe closes out The Rotter’s Club with a 33-page sentence nearly 14,000 words long. Lucy Ellmann’s Ducks, Newburyport contains only eight sentences sprawling across 1,030 pages. And László Krasznahorkai’s novella Spadework for a Palace is one single sentence—approximately 17,800 words—start to finish. Then again, what does he know? He only won the Nobel for Literature in 2025.

By the logic of the brevity brigade, these scribblers rank as failures. And yet, as Josh Jones observes of Faulkner’s labyrinthine sentences, “No matter how long and twisted they get, they do not wilt, wither, or drag; they run river-like, turning around in asides, outraging themselves and doubling and tripling back.” Sounds engaging. Sounds effective.

To understand where the evangelists of merciless concision go wrong, it helps to understand how sentences actually function. At the most basic level, a sentence brings a subject, verb, and object into a logical, syntactical structure: Mike washed his Jeep. That’s the nucleus. Everything else—dependent clauses, independent clauses, participial phrases, prepositional phrases, appositives, and all the rest—whir around the core like electrons, adding their own charge.

Just take that basic idea, Mike washing his Jeep, and try this on for size:

Racing the clock—Sarah hated when he was late, and he’d already kept her waiting last Tuesday—Mike attacked the mud caked on his Jeep like a man defusing a time bomb, the hose jerking in his white-knuckled grip, suds sluicing down the windshield, splattering the concrete, pooling in the driveway, his phone buzz buzz buzzing in his pocket (her, no doubt, already composing the shame-filled sigh she’d greet him with), and, worse, so much worse, he still had to shower and shave and change and whatever else before picking her up at seven, which was in, what, twenty minutes?

That single sentence runs 108 words, but despite the clustering clauses and phrases, it’s clear what’s happening: Mike’s screwed—and Mike knows it. What’s more, you can feel it. The sentence does more than describe his panic; by jamming all those elements before the long-awaited close, it enacts the panic and invites the reader to experience it with him.

The question isn’t how many words a writer employs but how clearly those words relate to the core. Length doesn’t cause problems. Muddled thinking expressed in clumsy writing does. Give a writer 100 words to build a sentence, and they won’t automatically become Faulkner, anymore than limiting a person to 15 makes them Hemingway.

The sentence serves the thought and desired effect, not the other way around. You can pile clause upon clause as long as the reader knows how each piece connects to the core. Confusion comes from losing the sentence’s center of gravity.

Maybe the rules help if you don’t know what you’re doing, but it would be better to learn what you’re doing. “No writer should delay the reader for no reason,” says Joe Moran in First You Write a Sentence:

If you stop the eye and check the reader’s pace, there must be something worth seeing. If she is driven back to the start of the sentence to double-check a pronoun’s antecedent or to work out which meaning of as or with you meant, then she has been waylaid into helping the writer do the writing. Such sentences are, like self-assembly furniture, unpaid labor.

No one’s buying their novels and memoirs at IKEA.

But Moran also knows that throwing obstacles in front of a reader contributes to the ride. He cites neuroscience research by a team at the University of Liverpool that showed readers’ brains lit up when reading difficult passages of Shakespeare compared to versions of the same passages that ironed out the Bard’s wrinkles.

“Readers seemed to like sentences that bent the rules without breaking them,” says Moran. “We want a sentence to be clear but not too clear, odd but not off-puttingly so, so that it can catch us off-guard and remind us that we are alive.” A stretchy sentence stretches us. Handled well, it’s a thrill.

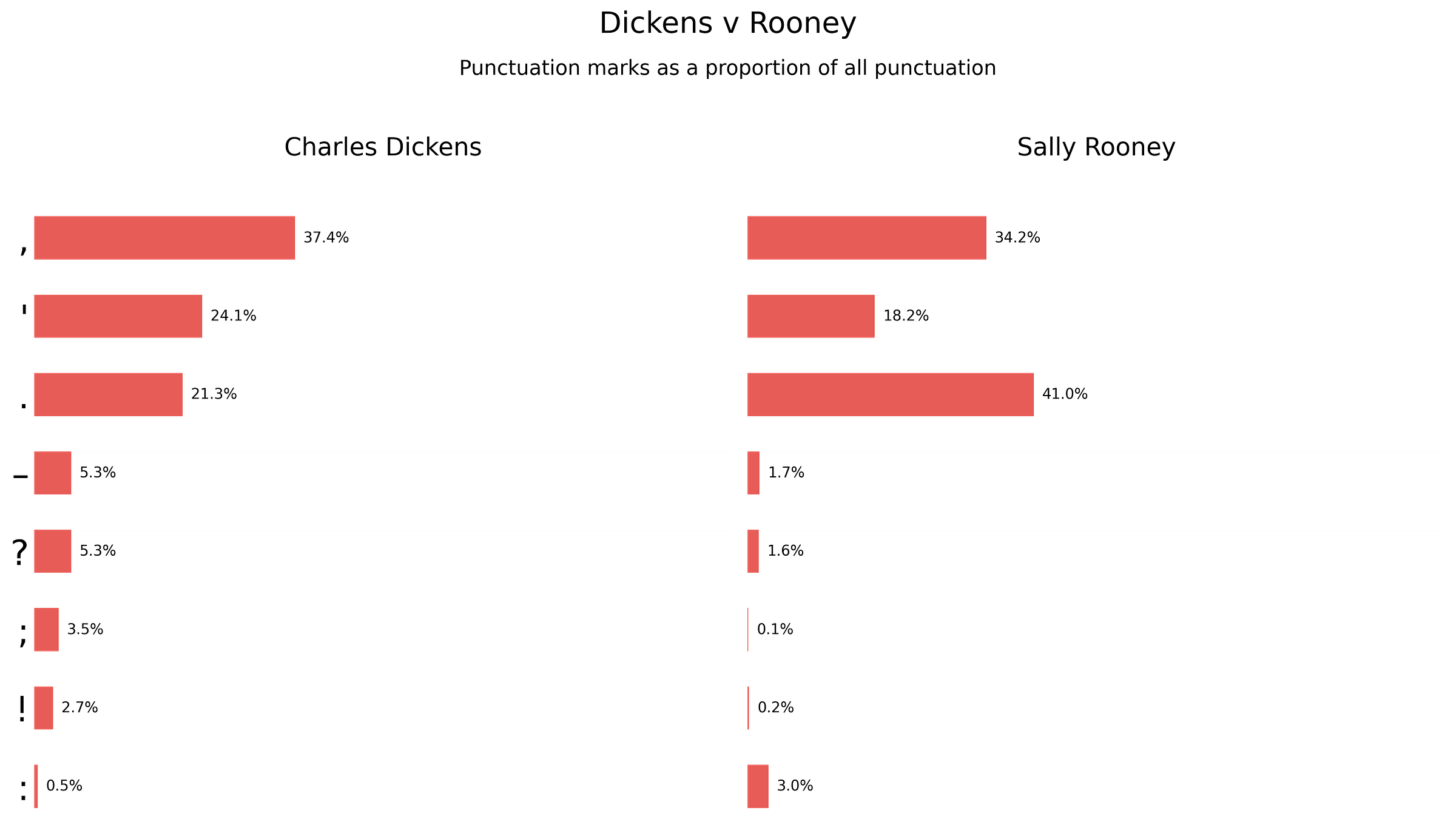

Having said that, writers do seem to write shorter these days; I emphasize seem for a reason that will emerge in a moment. Lee Child’s Jack Reacher novels average, as one study shows, around eight words per sentence; his genre forebear John le Carré clocks in at double that. Likewise, Sally Rooney uses twice as many periods as Dickens, a decent proxy for sentence length, and treats semicolons like used Kleenex.

But as the Dickens/Rooney comparison might indicate, much of what passes for shorter sentences may simply reflect changing punctuation conventions. As Henry Oliver points out in an essay for Works in Progress, we multiply periods today where the Victorians used semicolons and colons. But there’s not much difference in terms of the sense conveyed, nor the cognitive difficulty. The problem is that the short-sentence fetishists overlook the existence of—wait a minute, what’s that?—the paragraph.

Sentences don’t stand alone; they accumulate and congeal into paragraphs—observations, descriptions, arguments, composites of thought larger than any single sentence can contain. The paragraph is where narrative rhythm plays out, where writers push and pull, where dramatic tension builds and release occurs. The paragraph—not the sentence—is the unit of meaning readers actually process. This is why it’s roughly irrelevant if an author punctuates with periods instead of semicolons. They’re still asking the reader to do the same work in the paragraph.

The style-guide scolds justify their rules by appealing to working memory—after all, a reader’s noggin can only clutch so much at once. Fair enough. But working memory doesn’t reset after every period. A dozen choppy sentences with scanty logical threading will overwhelm working memory faster than one long sentence with clear syntax. Cognitive load accumulates one sentence to the next. Readers carry meaning forward, building comprehension sentence by sentence, within the paragraph.

I’ve told this story before, but I once had an author who refused to use paragraphs; he wanted every sentence on its own line. “That’s how I communicate,” he told me. “That’s not how people read,” I responded. My boss Brian had the opposite problem—an author who turned in a manuscript with no paragraph breaks at all. His agent called it brilliant. Guaranteed he hadn’t read more than a page; nobody could.

Both approaches fail for the same reason: meaning emerges from relationships between sentences, not from sentences in isolation, and the paragraph is what establishes those relationships. Fixating on average sentence length is like judging a song by the beats of individual notes. Congratulations! You’ve measured a thing! Meanwhile, you’ve utterly missed the music.

So who benefits from the universal rule that shorter is better? Maybe journalism (just don’t tell Tom Wolfe, famous for his long sentences). Business communications, naturally. Instruction manuals? Fine. But universalizing the rule is like advising every musician to finger out three-minute, four-chord pop songs because teenagers like them.

The real question is not “How long?” but “Does it work?” Is it interesting? Does it move? Does it, per Moran, catch the reader off-guard and remind them they’re alive? That’s art, not arithmetic, and the answer will never fit in an average word count.

If you’ve fallen for this horrendous advice, try writing a long sentence or two today and see how it feels. Rules don’t substitute for experimentation—or taste.

I’ve written a bit on editing over the years, and you might like to chase this piece with a few others along similar (though perhaps less crotchety) lines:

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends—or any writing coaches you know.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Thanks for a great reminder. Moran’s book is wonderfully useful to me—finish the sentence in your head before sloshing words around the screen. As my favorite Roberto Bolano said, to paraphrase, ignore all the rules.

What a splendid essay! Thank you for your astute insights communicated eloquently.