Note to Self: Watch Your Mouth

When We Don’t Speak Our Minds: Reviewing Glenn C. Loury’s ‘Self-Censorship’

Every now and then you read a book that seems to crack a code.

In Edith Wharton’s novel, The Age of Innocence, she describes upper-crust New York in the late nineteenth century as “a kind of hieroglyphic world, where the real thing was never said or done or even thought, but only represented by a set of arbitrary signs. . . .”

The details have changed, but our world is like that too. We live in a world where words can feel like loaded guns and we all have to watch what we say, or pay the price. We scan the social landscape looking to divine what is acceptable and weigh our utterances accordingly. We might not even be able to articulate why we feel the need to police our own speech, but it’s usually easier—and safer—just to keep our mouths shut.

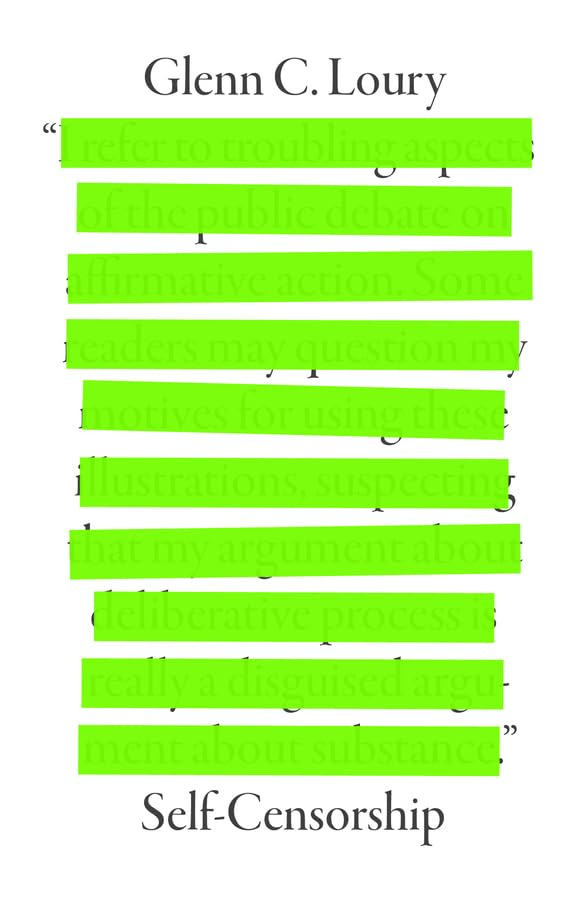

Thankfully, Glenn Loury’s Self-Censorship offers a Rosetta Stone for our hieroglyphic world.

You wouldn’t expect it. The core of this slender book is an academic essay he published in 1994 to describe the effects of what was then called political correctness on public discourse. What could an article published three decades ago have to say about our current moment? Everything, it turns out.

Whether we’re talking wokism, MAGA, Israel, gender, climate, cancel culture, whatever, you can map pretty much every modern sociocultural conflict onto Loury’s framework. And the result? It explains it all—or nearly so.

Loury’s core insight is economic. Nothing is truly free, and that includes speech. There is always a cost, however slight, to speaking our minds. If we deviate from audience expectations, the negative consequences, says Loury, “could be as modest as an eye roll or as weighty as sudden unemployment.” And so we self-censor—not because what we might say is indefensible or deplorable, but because we can imagine the possible cost of being misunderstood and would rather not bear the burden.

Loury notes that there are usually two levels a which a conversation functions. The subject in question provides the primary level: wokism, MAGA, Israel, gender, climate, cancel culture . . . God help us. But the secondary level involves questions about the legitimacy of those subjects and how they’re treated—which then triggers deeper questions about group norms, cohesion, loyalty, and the like. Hence the reason words can feel like loaded guns.

The naive blunder into such subjects with no consideration for the secondary level, get their head ripped off, and either sheepishly retreat or defiantly press on. The less naive spot the danger and either refuse to speak up or strategically parse their speech to avoid the blowback.

In any of those scenarios, the quality of public discourse is undermined. Not only does insincere, cynical, coded language prevail—hieroglyphics—but usually, says Loury, the most extreme views on either side tend to rise to the surface because it’s the prudent folks in the middle who tend to count the costs and keep their mouths shut. Cooler heads will prevail? Don’t count on it.

Why does this matter? Because real debates about real issues matter, even if—especially if?—they can’t be easily slotted into preapproved categories. “For every act of aberrant speech seen to be punished by the thought police,” says Loury,

there are countless other critical arguments, dissent from received truths, unpleasant factual reports, or nonconformist deviations of thought that go unexpressed or whose expression is distorted, because potential speakers rightly fear the consequences of a candid exposition of their views. As a result, the public discussion of vital issues can become dangerously impoverished. . . .

It’s possible to say that some conflicts are fundamentally intractable, even at the rhetorical level. But unless we understand how the rhetorical level comes into play, we don’t stand a chance of a decent discussion. We confuse the secondary level for the primary level. The literal meaning gets swallowed by the symbolic meaning.

Instead of clearly debating the issues, we’re blindly debating group norms, cohesion, loyalty, and the like—or we’re just self-censoring and opting out of the conversation altogether. When we do engage, we have to speak in euphemisms; we have to talk around the topic; we have to simultaneously say and unsay; we have to signal our virtue while trying not to undermine the claim.

All of this is compounded by the fact that we speak to many audiences. That was true even back in 1994 when Loury first wrote. But it’s quadruply true in the age of social media when, he says, “something said in one context will be available in all the others.” Social media raises the costs for clear communication because it means the prudent are forced to count additional costs and play it even safer.

As a result, says Loury, we live within a lie and avert our eyes to the real happenings of the world; subjects of real importance are couched in code or entirely avoided. Thus, society and individuals alike suffer from an act of self-protection. “If we cannot know what our friends, family, neighbors, and community truly think because they fear reprisal, we cannot know ourselves,” he says.

Social life abhors a discursive vacuum, and where self-censorship imposes diffident silence, true evil can creep in. We need only look to the former Soviet satellite nations to see how silence, enforced by fear, will be filled with suspicion, betrayal, and the shattering of social bonds.

And the costs can be quite personal.

Loury speaks about his reluctance to speak on the Gazan war for fear of coming off as anti-Semitic and then dealing the shame of not speaking up. We loathe our reluctance to speak because we then participate in the lie but feel as though we have no alternative. But, of course, that’s not entirely true. We have an alternative; it just requires courage—ergo, the sense of shame when we retreat into silence, whatever the cause in question.

“We can calculate the cost of speaking out,” says Loury. “But how can we possibly calculate the cost of shutting up?”

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below, 💬 in the comments, and share it with a friend!

More remarkable reading is on its way. Don’t miss out. Subscribe. It’s free, and all the cool kids are doing it.

Don’t miss this:

Self-censorship has always existed as a form of protection, but the possible reach and breadth of contemporary communications has drastically raised its influence and importance.

This is one reason people “on the spectrum” are valuable. They tend to be oblivious to how their blunt speech is likely to be received. It’s also why they get in trouble.