Robbed of a Father, Parented by Books

Library in Loco Parentis. Reviewing Farah Jasmine Griffin’s ‘Read Until You Understand’

As a little black girl readies for school one morning, her father stops and hands her two books. She expects to see him in his welder’s clothes for work—doesn’t expect to see him at all, actually. Shouldn’t he be on the job? Instead, there he is in a dress shirt and slacks, placing a pair of books in her hands.

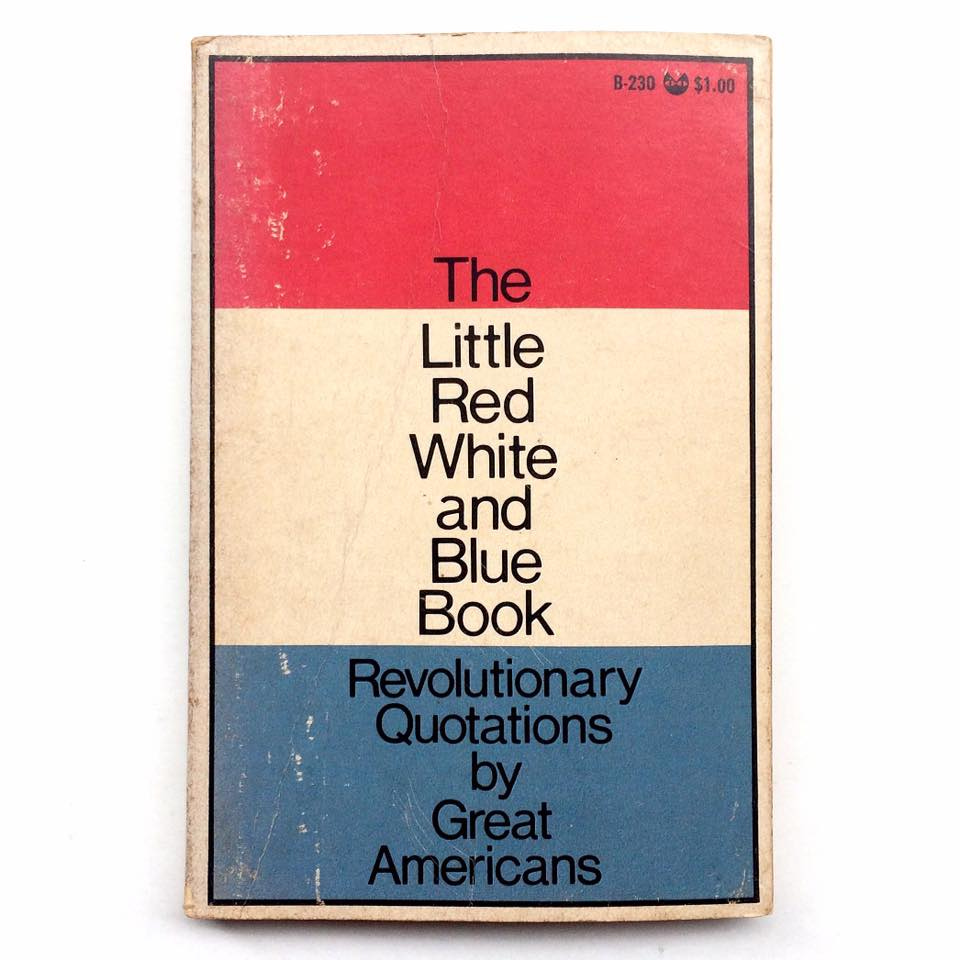

One of the two sports a cover with a band of red at the top, white in the middle, and blue at the bottom. It’s titled The Little Red White and Blue Book: Revolutionary Quotations by Great Americans. The other, Black Struggle: A History of the Negro in America, features the icon of a black man, his silhouette filled with the faces of forebears and exemplars: Sojourner Truth, Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and others.

As she looks through the pages, the girl sees her father has jotted notes, drawing her attention to one or another passage. “Start here Jaz,” she reads his scrawl in The Little Red White and Blue Book. “There’s lots of Frederick Douglass.” In the other, he inscribes this note, a poem:

Jazzie read this book You may not understand it At first. But read it and understand Daddy Baby read it until you understand Ask your teacher if you don’t understand She will like you for it. If you just know this book by the time I get home. I will be happy. Daddy

In a few hours the girl’s father will stand before a judge and explain why he has opted against paying a particular tax. He assumes he might be arrested and, unable to see his little girl for some time, wants to leave her something of himself in his absence.

As it turns out, nothing bad comes of the hearing. Farah Jasmine Griffin’s father, Emerson, was home that afternoon. But his notes were timely nonetheless. He died just a few months later under terrible, tragic, avoidable, negligent circumstances. Griffin’s memoir, titled after her father’s inscription, revolves around his death, its aftermath, and how black literature fathered her in his absence.

A Life in Letters

Today Griffin holds a professorship at Columbia University, where she also served as the first chair of the African American and African Diaspora Studies Department. Looking back, it’s easy to see the trajectory of her life paved with books. She inherited her father’s library after his passing, hundred of volumes, along with his jazz records. His legacy ignited a passion for learning and literature in his daughter.

“In the absence of my father,” she writes,

African American literature served as a constant spiritual and intellectual companion. . . . I was seduced by the power and allure of the language, by the ways words brought to life other times, places, and people, even as they made sense of my own present. As I began to read, and later to study, the novels, essays, and poems written by American Blacks, I learned that this body of literature bore witness to both the hypocrisy and the promise of the nation.

Emerson encouraged his daughter to read the American founders to understand that promise, fully cognizant of its persistent denial. The tension between the claim to liberty and inclusion, dignity and respect, and the daily experience of suppression and exclusion, injury and scorn, drives much of the drama in Read Until You Understand—not only the ups and downs of Griffin’s own story, but also the literary legacy of the black authors she studies and whose work she shares.

Griffin structures the book on series of themes. Mercy, freedom, justice, rage, and death take the first half of the book. Despite the darkness, light peeks through and then overtakes the narrative in the second as Griffin turns to love, joy, beauty, and grace.

She analyzes the qualities of these themes using moments in her own story, juxtaposed with episodes and passages from the lives and letters of authors such as Phillis Wheatley, Frederick Douglass, Richard Wright, Malcolm X, James Baldwin, Toni Morrison, and many other lesser knowns. Through close readings of their poems and prose she orients the reader to the struggle for the promise and her own coming of age.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free, and I’ll send you my top-ten quotes about books in your welcome email.

Griffin crept into the hollow left by her father and filled it with words. “I wrote stories and poems about my father,” she says, “about my parents’ love story, about characters I invented. A compulsion to read and write addressed my loneliness and seemed to release something close to euphoria in my head.”

She found room on her shelves for Mark Twain, Mario Puzo, Edith Wharton, Charlotte Brontë, T. S. Eliot, James Joyce, and Fyodor Dostoevsky and dropped them into productive exchange with the black authors she loved. “Wasn’t James Baldwin’s Go Tell It on the Mountain similar to A Portrait of the Artist? Weren’t Morrison’s literary gifts as extraordinary as any modernist?”

Mercy, Justice, and Love

While her father had rejected belief in God, Griffin discovered evidence of divine mercy in the wake of his death: acts of kindness from family and friends, gifts of food, money, and the generous presence of others—not to mention literature itself.

Along with experiencing mercy directly, Griffin found the theme treated in Phillis Wheatley, Toni Morrison, and Charles Chesnutt. Its proper application, givers, and recipients, however, weren’t always clear. “If mercy is defined as being spared the punishment you deserve,” she asks,

who actually is in need of it: the African child, or those who capture and enslave her? . . . If mercy is granted to those who deserve punishment for their deeds against others, then in many ways the United States, particularly its white citizens, have been among the greatest recipients of mercy. It would seem they are in need of it.

It’s easy for some of us to push that need for mercy into the past, as far back as we can manage, out of self-protection. But Griffin won’t quite let us get away with it. She brings Frederick Douglass into conversation with Malcolm X, and Malcolm X with Barack Obama, drawing forward people and events. She shows how the past persists and pesters the conscience, while the present finds new reasons to accuse:

Michael Brown

Eric Garner

Tamir Rice

Sandra Bland

Freddie Gray

Philando Castile

Ahmaud Arbery

Breonna Taylor

George Floyd

Lest we lose hope while such lists grow, Griffin reminds us that justice, though elusive, is possible. It is, in the words of Fania Davis, “love correcting that which stands against love.” Such love is ultimately transformative. “While I am uncertain that love can always transform those who embody evil, those sociopaths who lack a conscience,” says Griffin, “I do believe that the force of love can defeat and destroy such evil.”

Why? Because, she explains, “Love requires us to see each other and to commit to each other’s humanity. . . . This kind of love is the basis of justice. This love is the conduit of freedom. This love is power beyond wealth, greed, and physical might.”

Producing and Protecting Beauty

As if to rhetorically underscore the transformative effective of such love, Griffin’s narrative turns a corner to embrace joy and beauty. While the memory of her father never fades, the picture of Griffin’s mother, Wilhelmena, comes more fully into view. “I am the daughter, granddaughter, and great-niece of seamstresses,” she writes. “I spent hours in bookstores with my father; hours more in fabric stores with my mother.”

Through her craft, Griffin’s mother brings beauty into the world, and beauty has its own power to turn back the grim and unfortunate forces of the world.

Along with producing beauty, Wilhelmena actively protects it. When a teacher told some of Griffin’s classmates that Griffin wasn’t “cute,” Griffin felt hurt and told her mother. “Listen to me,” said Wilhelmena. “I am only going to tell you this once. . . . You are beautiful. I haven’t wanted to tell you because I didn’t want you to value your looks too much. . . . It says nothing about your heart or your intelligence or your kindness.” There’s more to the story, but Griffin’s takeaway is priceless:

What I remember most about that moment was thinking, “My mother thinks I’m beautiful. Wow.”

As the father of a young black daughter who wants her to always know and trust in her own deep beauty—along with her heart, intelligence, and kindness—I wasn’t just moved by this passage; I was mowed right over.

The Need to Cultivate

The final moments of Griffin’s memoir unfold in the “gratuitous beauty” of gardens, reminding us that “though the world is full of ugliness, meanness, hatefulness, there is always, also, this: Grace, unmerited reward given to humans by the Divine. There is nothing we can do to earn it. It just is.”

The weeds we’ve sown or failed to uproot threaten the promise prized by Griffin’s father, Emerson, plus countless others and deserved by all. We don’t (can’t!) earn grace, but neither do we accept it passively. Like gardens, mercy, justice, love, and beauty all require intentional cultivation to flower.

We can find models of our necessary labor in the literature we read. But we must incarnate the goodness we discover in words and actions of our own, words and actions that refresh, restore, and redeem.

Thanks for reading. If you’re enjoying Miller’s Book Review 📚 please spread the love and share it with a friend!

And if you’re not a subscriber, take care of that now. You’ll be glad you did.

Immediately added to my TBR list. Thank you!

Well, now I am adding that one to my wishlist. What a story! Thanks for sharing.