Fab Chore: Writing about the Beatles and Other Music Greats

U2, Marvin Gaye, Johnny Cash, Van Morrison, More: How Biographer and Music Journalist Steve Turner Stays So Productive

Steve Turner began his career in music journalism in 1969 when the Beatles Monthly published his first article. Along with serving as features editor of Beat Instrumental in the 1970s, he went on to write for Rolling Stone, Melody Maker, NME, Mojo, Q, the London Times, and other publications.

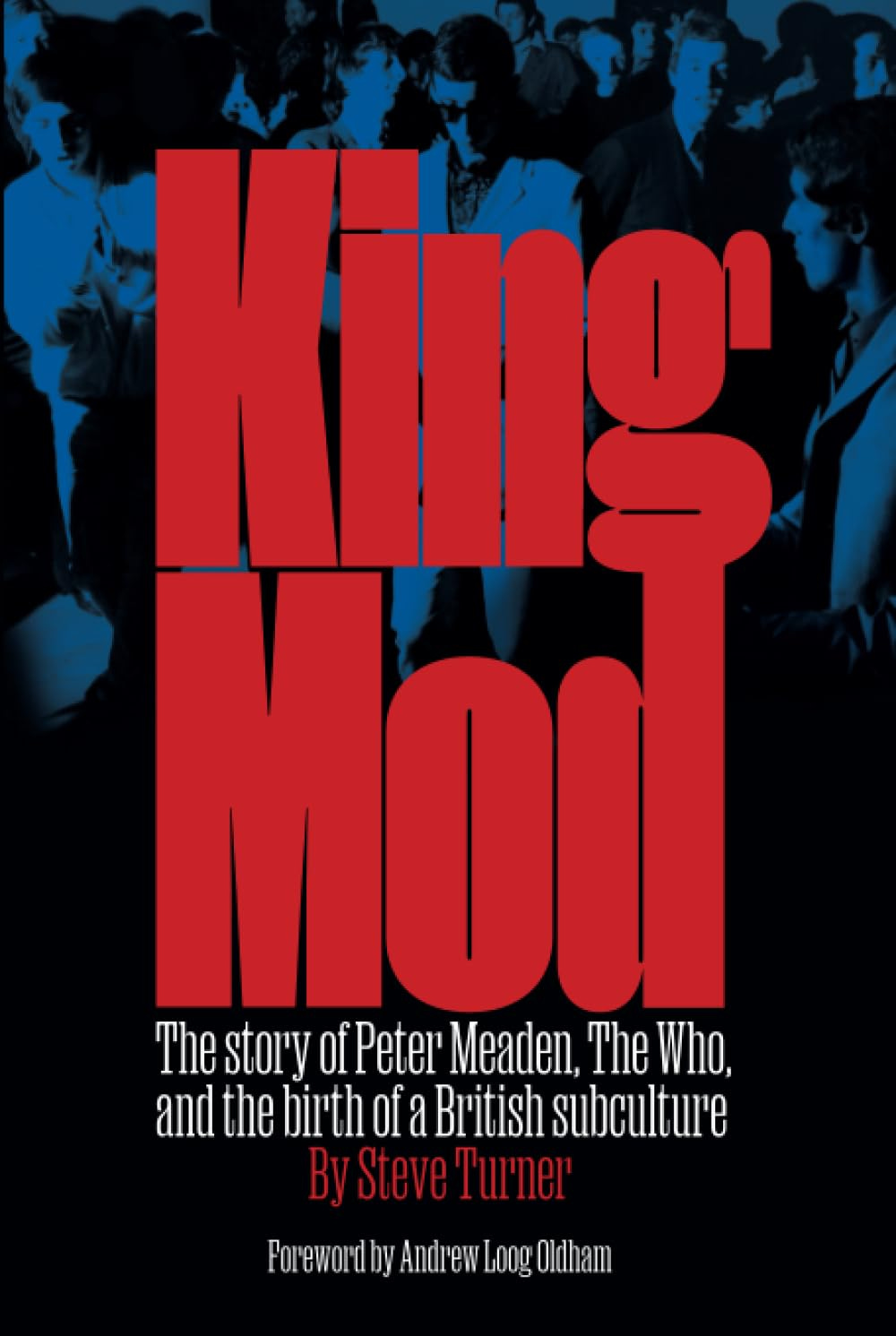

He’s the author of several biographies, including Cliff Richard: The Biography (1993), Van Morrison: Too Late to Stop Now (1993), Jack Kerouac: Angelheaded Hipster (1996), Trouble Man: The Life and Death of Marvin Gaye (1998), The Man Called Cash: The Life, Love, and Faith of an American Legend (2004), and most recently King Mod: Peter Meaden, The Who, and the Making of a Subculture (2024). As a literary collaborator, Turner coauthored Conversations with Eric Clapton (1976), U2 Rattle and Hum (1988), and also penned Linda McCartney’s Sixties: A Portrait of an Era (1992).

The Beatles have formed a central preoccupation for Turner over the years. He’s written several acclaimed books on the Fab Four, including The Gospel According to the Beatles (2006), Beatles ’66: The Revolutionary Year (2016), A Hard Day’s Write: The Stories Behind Every Beatles Song (1994; updated in 1999, 2005, and 2009), and The Complete Beatles Songs: The Stories Behind Every Track Written by the Fab Four (2015).

Turner’s music writing goes beyond contemporary culture. In 2005, he published Amazing Grace: The Story of America’s Most Beloved Song; in 2010, An Illustrated History of Gospel; and in 2011, The Band That Played On: The Extraordinary Story of the 8 Musicians Who Went Down with the Titanic—a book I had the privilege of acquiring for Thomas Nelson. I’d been looking for an excuse to work with Steve for years by then.

If all this weren’t enough, Turner has also written several books on the intersection of faith and the arts, plus popular works of poetry, especially for children. In this conversation we discuss, among other things, how he does it.

You’ve written extensively about the Beatles. What’s the most misunderstood or neglected aspect of their legacy?

I think it’s what I covered in The Gospel According to the Beatles, which is the spiritual questing that informed their work from 1965 onwards as they became more reflective and then, post-1966, more confined to the studio. My book covers their lives and career as a journey from childhood church experiences and teenage atheism through existentialism, drug-induced changes in consciousness, meditation, and imagined utopias.

I still feel the book has been overshadowed by my other books about the Beatles, A Hard Day’s Write (the stories behind their songs) and Beatles ’66 (“one year in the life of”).

“My book covers [the Beatles’] lives and career as a journey from childhood church experiences and teenage atheism through existentialism, drug-induced changes in consciousness, meditation, and imagined utopias.”

—Steve Turner

Take us back to the beginning: How did you first get involved in music journalism? Was there a specific moment or experience that got you going?

I was aware of a new type of coverage of popular music, spearheaded in America by magazines like Rolling Stone, Crawdaddy, and Creem and followed up in the UK by writers like Tony Palmer contributing to The Observer where rock records were treated with the same seriousness and depth usually accorded to criticism of theater, fiction, or film. My parents, in common with a lot of other parents at the time, thought pop music was a “fad” that we would grow out of. I didn’t think so.

In the summer of 1969 I was reading through an issue of The Beatles Book Monthly, the group’s official fan magazine, and came across a feature written by a provincial journalist on his view of the Beatles. “I could do as well as that,” I thought, but instead of leaving it there I wrote a 800 word piece, sent it in, and forgot about it.

A couple of months later I had a letter from the publisher/editor saying he assumed I’d seen my piece in the magazine, enclosing a check and asking me if I could write some stories for another magazine he published called Beat Instrumental. To cut a long story short I did so, and a year later—after interviews with Black Sabbath, Marc Bolan, and Rod Stewart—I was offered a staff job at Beat Instrumental in London.

Beyond the Beatles, you’ve covered a variety of musicians and cultural figures: Johnny Cash, Marvin Gaye, Van Morrison, and most recently Peter Meaden, the man who discovered The Who. Who was the toughest to write about and why?

Van was tough because close to publication he threatened to sue me for libel, although I think that just drew attention to the book and helped sales. Marvin was tough because it was a dark story ending in murder.

One of the problems I experience with writing about Americans is that you find interviewees who’ve been close to the subject who think they have the whole story and want you to pay them for it. Some of them even have a clear idea about who should play them in any movie adaptation.

The Band That Played On, the story of the Titanic musicians, was tough because I had to build family trees for these men who died in 1912 and then find surviving descendants.

“Van [Morrison] was tough because close to publication he threatened to sue me for libel, although I think that just drew attention to the book and helped sales.”

—Steve Turner

Who was the most fun?

My first full-length biography was of Cliff Richard, one of Britain’s most consistent hit-makers who was a star even before the Beatles arrived. I had Cliff’s blessing write the book (although no editorial control) and Cliff was always a wonderful person to spend time with.

Doing the text for Linda McCartney’s photo collection Sixties: Portrait of an Era was fun because it was through this project that I met Paul for the first time and spent time at their home in the country. I had a few “pinch me” moments doing that.

Having written about them all—and others in your work as a journalist—can you look back and see connections across their lives and careers? What do all of those figures have in common as artists, as creators?

They all have a spiritual niggle in their lives and are all rebels of one kind or another. People like Jack Kerouac, Marvin Gaye, Bono, Pete Townshend, Johnny Cash, John Lennon, John Newton, and Marvin Gaye all had childhoods with a good dose of old-fashioned religion and it seemed to give them a foundation for what were the Big Questions in life.

I only require that my subjects at least ask the important questions, not necessarily that they reach orthodox conclusions. That would be a bonus. To write a biography of someone is like moving in with them for at least a year so there has to be a great deal about them that you actually like about them, otherwise you’ll get frustrated and may even want to walk out on them.

“To write a biography of someone is like moving in with them for at least a year so there has to be a great deal about them that you actually like about them, otherwise you’ll get frustrated and may even want to walk out on them.”

—Steve Turner

What has McCartney and Lennon’s songwriting taught you about prose?

They taught me more about poetry because alongside my journalism and biographies I’ve authored ten books of poetry, six of them for children.

I loved the way that they tackled so many different styles and genres. Only on a couple of occasions do two Beatles songs sound similar, and yet they’re all distinctively Beatle-ish. I tried for that variety in my poetry. John’s poetry writing in his books In His Own Write and A Spaniard in the Works were also inspirational on my writing for children.

So much goes into a biography—archival research, interviews, writing, and more. What part of the process delights you most?

I enjoy the research. I especially like it when you make breakthrough discoveries by being persistent in your questioning. The largest percentage of writing a biography takes place away from the keyboard. When you first start putting actual sentences in place, it feels like you’re heading for the finish line. All the stuff you’ve been filing away suddenly finds form of expression.

In the 1960s I saw a magazine feature about the spy writer Len Deighton and he was photographed with a primitive computer and reams of paper and spoke about research. I found that very exciting.

“The largest percentage of writing a biography takes place away from the keyboard. When you first start putting actual sentences in place, it feels like you’re heading for the finish line. All the stuff you’ve been filing away suddenly finds form of expression.”

—Steve Turner

What’s the most grueling?

I think the rewriting, the time when the manuscript is going between specialist readers, fact checkers, and line editors—and possibly even legal and copyright experts. However much you check every line, there are always spelling mistakes that slip through.

Every research project involves discoveries, in some cases quite notable. Looking across your body of work, what are your favorites?

The big discovery in The Band That Played On was that the violin played by band leader Wallace Harley had been discovered and was being evaluated by an auction house. It later went on the market and was sold, but the book was the first to alert the world to its existence.

Researching Trouble Man, my biography of Marvin Gaye, I was told that Marvin’s son, known as Little Marvin, had been adopted by Marvin and his wife Anna Gordy (sister to Motown founder Berry Gordy). Another source told me that although he was adopted he was Marvin’s biological son. Yet another source told me it was the son of an unmarried niece of Anna’s.

It had been important to the family that the son have both Gaye and Gordy blood. I tracked down the niece, Denise Gordy, and called her on the phone. She was so taken aback at being discovered and traced that she told me everything. I published the fact in my book but didn’t make a feature of it.

When my findings were mentioned by the Biography Channel, Denise Gordy threatened to sue me, saying that the story was untrue and she had never spoken to me. I was patched in to a conference call between Gordy, her lawyer and the Biography Channel and its lawyer.

Fortunately, I had a tape recording of my call to Denise, a transcript of the conversation, and phone-company records of the date and time of my call, which I was able to supply as defense evidence. My tape was played by the Biography Channel lawyer and a few second later Denise Gordy’s lawyer said, “Miss Gordy has left the room,” and that was the last I heard of it.

For A Hard Day’s Write I spoke to Julian Lennon both about “Hey Jude” and “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.” Julian told me that his kindergarten painting of his friend Lucy O’Donnell that had inspired the song was owned by a well-known rock guitarist. I was then able to go and photograph it. When I used it in my book, one reviewer said that it was worth paying the price of the book just to see that photo.

Researching Amazing Grace I discovered the building plans for the Greyhound, the ship that John Newton was on when he underwent the violent storm that played a vital role in his conversion from slave trader to preacher and hymn writer, and these plans revealed that the owners had skimped on nails and bolts in order to bring down the cost. This was obviously why the boards of the ship began to split apart during the bad weather and let the water in.

How have you remained so prolific over the decades?

I don’t know if I have been prolific. I’m more conscious of time spent building proposals when I could have been writing books and projects I invested time in that didn’t take off. Sticking to a vision of what I should be doing has meant turning down opportunities that were less than the best.

Some things have happened because I had a strong idea and stuck to it doggedly, but others come out of the blue—like getting a call from a publisher who wanted to do an authorized book with Johnny Cash and when asking around for a suitable writer my name came up. Or getting a call asking if I’d like to work with a photographer to provide text for a picture book and later being told that the photographer in question was Linda McCartney.

I think you last longer if you stay true to something that is uniquely you. If you do anything and everything, you might have a few bumper years, but in the long run people don’t associate you with any particular subject or viewpoint and you become forgettable. I think it’s important to constantly return to whatever it was that made you want to write in the first place and try to rekindle that spirit.

“I think you last longer if you stay true to something that is uniquely you. If you do anything and everything, you might have a few bumper years, but in the long run people don’t associate you with any particular subject or viewpoint and you become forgettable.”

—Steve Turner

What are the three best music biographies or autobiographies you’ve ever read?

The ones that have been inspiration to me are:

The Beatles by Hunter Davies because it was the first proper biography of the Beatles and Davies, who was Sunday Times journalist rather than a pop critic, had access to witness them composing songs and met their parents and, in the case of John Lennon, the aunt that raised him;

Elvis by Albert Goldman because he spoke to so many people, and went in to so much detail; and

Divided Soul, David Ritz’s biography of Marvin Gaye, which did a good psychological evaluation of the man and wrote about the inner battle between the faith Gaye received as a child and his fleshly desires.

Is there a through-line to your varied work? Is there a particular message or understanding you think comes across? What do you hope your readers take away?

I didn’t plan it this way but everyone I’ve written about has been a questioner, a thinker and someone who has grappled with the classic Big Questions. I’ve also always been interested in the ways in which artists are both shaped by the culture and in turn shape the culture.

I’m curious to make sense of my life (mostly done in poetry) and to make sense of the world by the light of experience and my Christian faith. I hope my readers will come to value the Big Questions. One of my poetry books for children, I Was Only Asking, tried to encourage the same thing.

If you could choose one musician or cultural figure to write about next, who would it be and why?

I would love to have written about Dylan. I’ve written about him in other books and have even met him (briefly), but I’ve never had the opportunity to do a book. I’m not sure if there’s a gap unless it was a book done with his full cooperation.

Final question: You can invite any three authors for a lengthy meal. Neither time period nor language is an obstacle. Who do you pick, why, and how does the conversation go?

William Blake, Woody Allen, and the author of Ecclesiastes. I went to a reading of Blake’s poetry when I was sixteen, and it set me on my path. It made me want to write and to perform. When I started to write for children in the 1990s, Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience remained a guiding light.

I’ve always loved Woody Allen’s metaphysical humor and the way he has been consistently driven by questions about love, sex, and death. We need people like him to keep the questions alive.

Ecclesiastes is a remarkable and elusive piece of literature which I first read when someone compared it to Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot and other absurdist plays. I have just finished writing a collection of poems which is my response to the thoughts contained in Ecclesiastes. At this meal Woody agrees to write a foreword to my book.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this review, please share it with a friend.

What if you’re not a subscriber? Easy! Take a second and sign up. It’s free.

Before you go . . .

"The author of Ecclesiastes" -- now THAT'S a dinner guest!

“I didn’t plan it this way but everyone I’ve written about has been a questioner, a thinker and someone who has grappled with the classic Big Questions.”

We often talk about how authors write books that grapple with the Big Questions. It’s good to be reminded that literature is not the only medium for exploring questions; music and all other types of art can wrestle with them too. The discernment comes in finding those interested in asking the Big Questions, as Steve said.