Globalization and Its Discontents: 16th Century Edition

Competing Stories about the World. Reviewing ‘The History of Water’ by Edward Wilson-Lee

The stories we tell shape the world we inhabit, and our many conflicts are often the products of dueling narratives. Edward Wilson-Lee’s A History of Water involves two such competing tales told by two different writers, both living at the dawn of globalization and world trade.

Luís Vaz de Camões (c. 1524–1580) is today recognized as Portugal’s greatest poet, on par with Shakespeare. Skulking around the Lisbon underworld and occupying various prison cells, his early years showed little promise. He jockeyed for fame writing verse but failed. He saw military action in Ceuta, North Africa, losing his right eye. Finally, he was indentured and exiled to India: “a banishment that would only be lifted when he brought back something that would merit a reprieve,” says Wilson-Lee.

Thankfully, the odds of bringing back something meriting reprieve seemed strong.

From Epic Failure to Epic Fame

Portugal had been the first European nation whose ships sailed around South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope to trade in the Indian Ocean. Until then the spice trade brought prized eastern wares overland, enriching a chain of middlemen along the way. Advancements in navigation meant the Portuguese could now go directly to the source. Thanks to explorer Vasco da Gama, they did.

Camões rounded the Cape more than fifty years after da Gama. By then, the Portuguese had built a network of ports and forts they could call an empire. Camões served in various capacities, sometimes on land sometimes at sea, principally at Goa, India, but also at Macau, China. On his return from Macau—prompted by charges of embezzlement—his ship went down.

Bad as that might sound, Camões’s luck had finally edged ever so slightly upward. Marooned in the Mekong Delta, he had managed to save his only possession of real value: a draft manuscript of his epic poem lauding and gilding da Gama’s many feats. Lusiads, or “Song of the Portuguese,” eventually secured Camões his long-sought fame, winning him the praise of his countrymen and affection of poets and other writers centuries on.

Says Wilson-Lee,

The Romantics adopted Camões as a model for their own ideas of the poet, as a wanderer and a figure of exile, and his story and writings served as inspiration to Wordsworth, Melville, and Edgar Allan Poe, with commentaries written by Friedrich Schlegel and Alexander von Humboldt and a translation by Sir Richard Francis Burton.

But, as Wilson-Lee points out, Lusiads underscores what we tsk-tskingly call eurocentrism. Camões created a mythic picture of Portuguese greatness that succeeded only by obscuring and omitting the cultures, peoples, and histories that formed the backdrop for his epic. In one scene, for instance, Camões’s da Gama finds a frieze of Indian deities to whom he gives Greco-Roman names. He then mentions Alexander the Great’s conquests as far as India and says, more or less, that da Gama’s efforts completed the work.

“In Camões rendering,” says Wilson-Lee, “the Indians have been almost wholly written out of their own history. The names of their gods are gone, their art is given over to the Greeks, and they are present only as the subjects of a long series of conquests, of which the Portuguese is the latest.” Such narratives are as incurious as they are dishonest.

Damião de Góis, the other principal character in Wilson-Lee’s story, knew better.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free, and I’ll send you my favorite quotes about books and reading.

A Different Vision of the World

Damião (1502–1574) served as chief archivist in the Lisbon’s royal archive, the Torre do Tombo, Tower of Records. He also traveled widely, though not across the routes that Camões followed. In various capacities, Damião traveled to north first to Antwerp, and then to Gdansk, Wittenberg, Krakow, as far as Moscow.

His itineraries and interactions conjure some of the most notable names of the period, for instance:

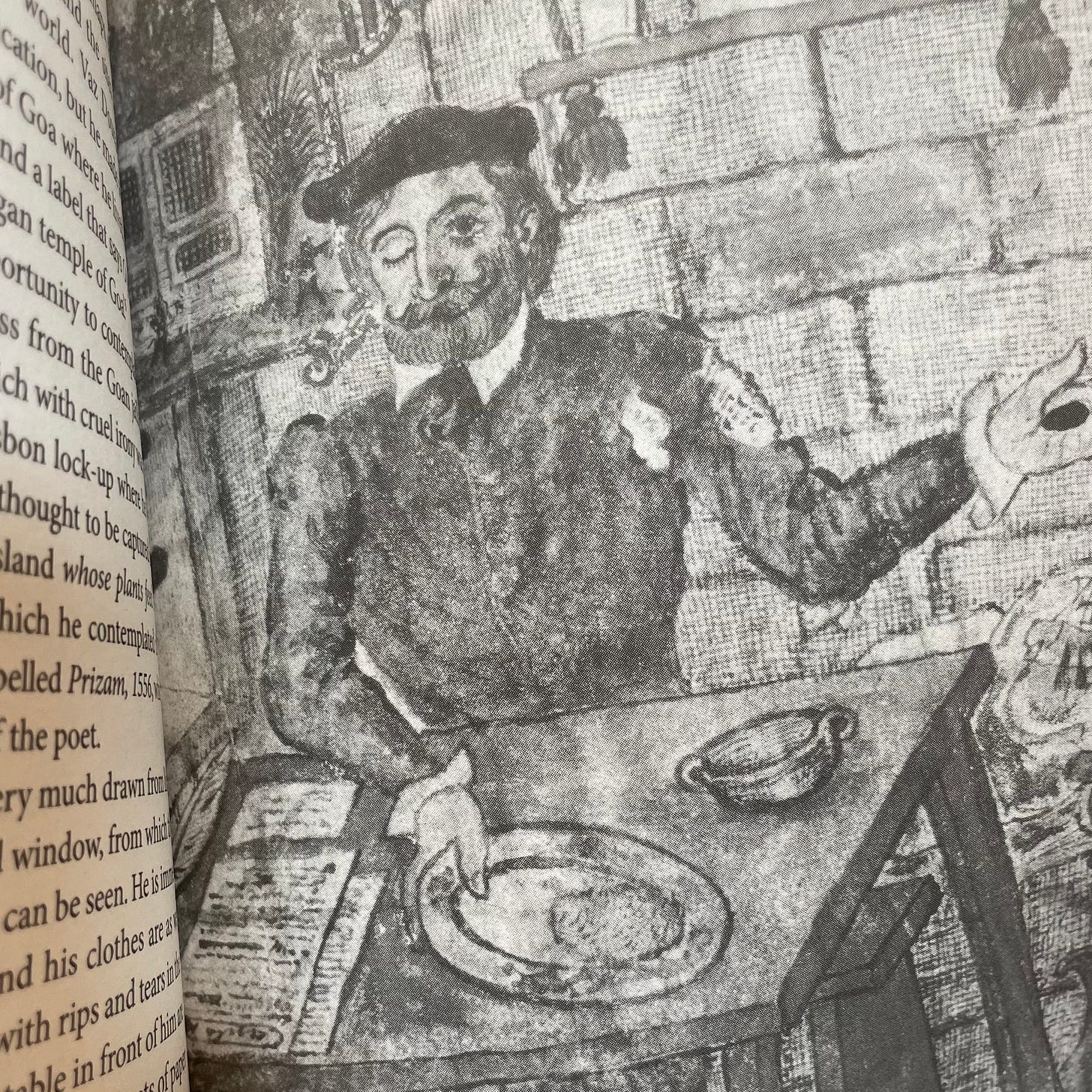

Albrecht Dürer: responsible for the engraving of Damião above.

Hieronymus Bosch: Damião owned three of his eccentric, experimental paintings.

Martin Luther: Damião dined with him and Melanchthon in Wittenberg.

Erasmus: Damião served as his secretary for several months.

Damião also showed affinity for novel art forms, including polyphonic music. Alas, his catholic tastes were a bit too catholic, ironically, for the Catholic Church of the day. Damião dreamt of reuniting the Roman Church with the Ethiopian Church and the various Protestant communities. He was prone to speaking liberally about it, much to Erasmus’s chagrin. “When popes and emperors make the right decisions I follow them, which is godly,” said Erasmus; “if they decide wrongly I tolerate them, which is safe.”

Damião did not follow employer’s example. Though like Erasmus he never left the Catholic fold, Damião hoped to see its rifts healed and its boundaries enlarged. And his conversations and related actions distressed some who discovered them—including the Inquisition, thanks to the reports of one of his interlocutors.

When the authorities finally published the indictment against Damião it was full of typical charges: that he consorted with heretics, flouted the traditions of the Church (especially fasting rules), and consulted prohibited books. Portugal led Europe in publishing a list of banned titles, though as the royal archivist and a humanist scholar it’s not at all odd that Damião possessed several. In fact, all of Damião‘s actions could have been lent more generous interpretations had his inquisitors desired; instead, they seemed bent on finding fault.

After nineteen months of grueling investigation during which Damião‘s health precipitously declined, the authorities decided to spare him execution and banished him to a monastery. Somehow, fifteen months after the verdict, he was out traveling and was murdered—either burnt or strangled—the perpetrator never identified.

But What about That Title?

No one will blame you if you assume A History of Water deals with hydraulics. But it’s a metaphor, possibly in reference to the currents that carried Camões eastward and Damião north to Antwerp. More likely, however, the metaphor describes the go-where-it-will flow of history itself.

One of Damião’s jobs as archivist was to prepare a history for the Portuguese king. His completed book represents a diametrically opposed vision of global history than that presented in Camões’s epic poem. Whereas Camões’s travels somehow constrained his view of the world, Damião’s view broadened and expanded. As news and reports of the world followed paper trails through the royal archive, Damião made sure to include everything he could. His taste for polyphonous music paralleled his method for writing history. Writes Wilson-Lee,

In Damião’s hands, the history of Portugal, and even of Europe, began to come loose at the seams. So full are his chronicles with accounts of the kingdom of the Monomotapa, the customs of the Gujaratis, speculations on the giant stone horseman found in the Azores, the genealogy of Shah Ismail of Persia and the beginnings of the Shia faith, and descriptions of the eating habits in Hormuz and Malacca, that it is difficult to say precisely whose history this is.

Camões presents a clean and narratively tidy picture of the world, his favorites at the center, their deeds always just and honorable, other peoples marginalized or left out entirely. Damião, on the other hand, shows us the world in flux, a fluidity he recognized was part of history itself, one where categories fail and perspectives are subject to revision as new information flows into view. “History is infinite,” wrote Damião, “and so its virtues are also interminable, and cannot be confined within any limits.” Like the sea.

It’s Camões and Damião’s dueling views of the world that constitute Wilson-Lee’s primary interest in their story. And given the competing social, cultural, and political visions at play in the western world today, I think it’s safe to say that we’re still living that same story.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this review, please share it with a friend.

More remarkable reading is on its way soon. Subscribe today so you don’t miss out!

Breathtaking history.