Based on a True Story: Dostoevsky’s Classic Novel

Inspiring ‘Crime and Punishment.’ Reviewing ‘The Sinner and the Saint’ by Kevin Birmingham

The advice every writer hears at one point or another? Write what you know. Whenever I hear those words I wonder, How do you explain murder stories?

Dostoevsky wrote a classic one. He published Crime and Punishment in serial form beginning in 1866. The effect was sensational. Nothing like it had appeared before, and the audience eagerly awaited each new installment. But folks weren’t on the edge of their seat wondering about the murderer’s identity. No, readers knew the killer after the end of the first issue.

The mystery was why Raskolnikov would kill the old pawnbroker and her sister in cold blood. Raskolnikov doesn’t really know himself. As some have said, Crime and Punishment is not a whodunit, but a whydunit. And so the novel bends a turns through the crooked paths of the killer’s psychology, edging us page by page closer to the truth.

But where did the story come from? That’s what Kevin Birmingham attempts to answer in The Sinner and the Saint, a biography not so much of Fyodor Dostoevsky but of one of his most enduring novels.

Education of a Writer

Dostoevsky decided to become a writer at a time when the choice seemed farfetched and foolhardy. In nineteenth-century Russia, nobles with income from land and other ventures penned novels. Dostoevsky’s family possessed some minor rank, but his mother died when he was young, and his father was murdered by the few serfs in his care. Alone except for his siblings, Dostoevsky ventured into the literary wilds with no other form of support.

He caught an early break. Russia’s biggest literary critic, Vissarion Belinsky, read Dostoevsky’s debut novel, Poor Folk, in manuscript. He loved it. “Do you, yourself, realize what you have written?” Belinsky asked when they met. “Have you comprehended all the terrible truth that you have shown us?”

Belinsky touted Dostoevsky in public and mentored him in private. He exposed him to socialist politics, atheism, and the whole heady brew of radical philosophy wafting in from Europe. Dostoevsky never bought in completely, but he was energized by the world of consequential ideas and the literary tussle between traditionalists and progressives. He also became and advocate for ending serfdom and elevating the rights of women.

He found himself a marginal member of the radical Petrashevsky Circle—and also under surveillance by the tsar. Police eventually arrested the whole crew for seditious behavior: mostly chatter about radical ideas and securing an unlicensed printing press to distribute anti-government literature. Members of the circle were questioned, convicted, and sentenced to die. While Dostoevsky and the others awaited death by firing squad, their sentences were—seconds before the command to shoot—revised: exile to Siberia.

Dostoevsky, grateful his life was spared, spent several years in exile and several more in mandatory military service. When his time was up, he ran back to civilization to do . . . what, exactly? The same restrictions on speech that exiled him also prevented him from publishing again. We sometimes forget the value afforded by the First Amendment and other free-speech immunities assumed elsewhere in the liberal world. Russia recognized no such freedom. Censors determined what could and could not be printed.

Thankfully, Dostoevsky was granted dispensation, mostly owing to his former reputation as a writer of some promise. But his literary comeback proved tough to manage. To aid the effort, he and his brother started a publication called Vremya, or Time. So-called “thick journals” then dominated Russian literature. These journals offered a selection of original fiction and essays, recycled European news, and other interesting bits and squibs in serial format.

Education of Sociopath

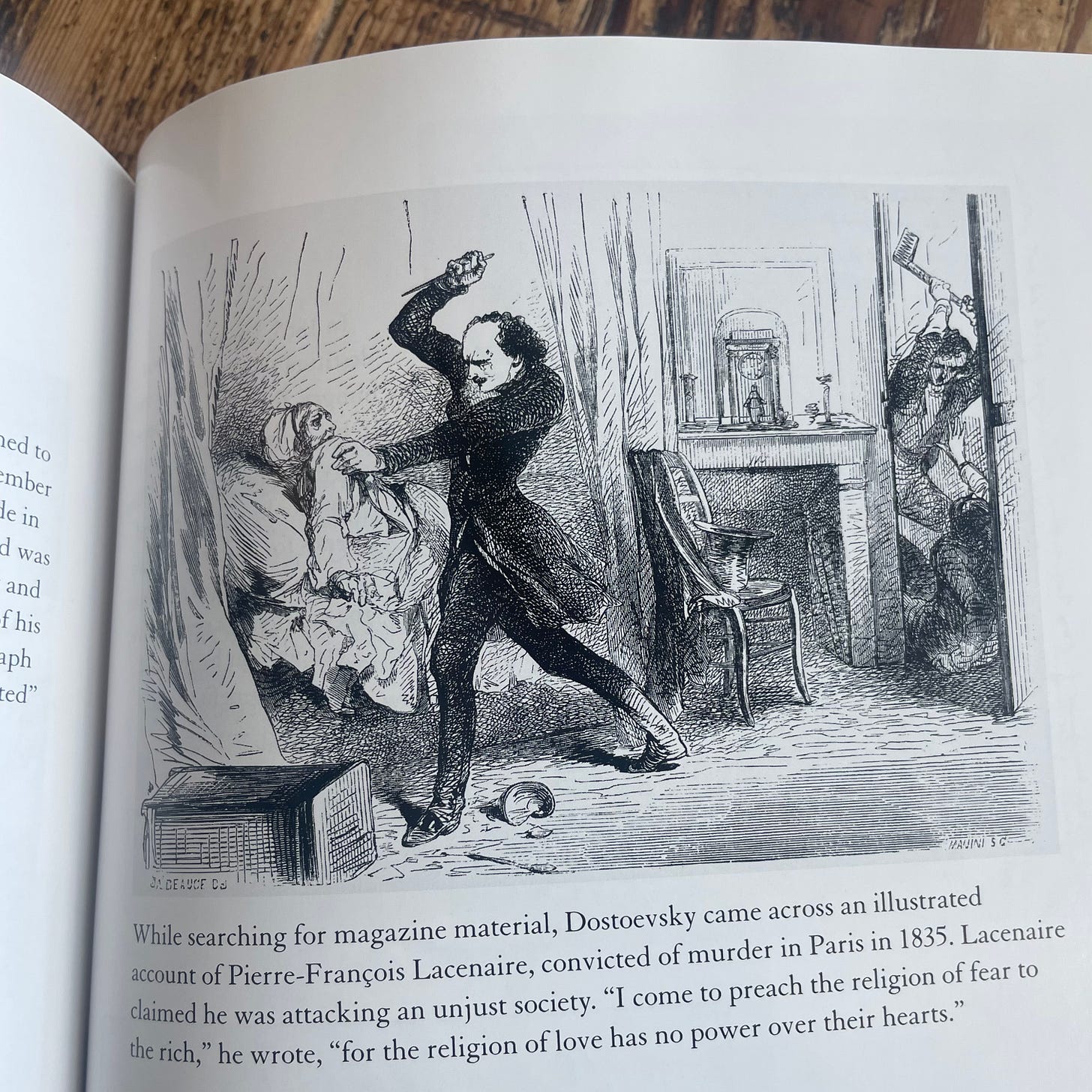

Looking for material to fill out their second issue in winter 1861, Dostoevsky came upon the story of a failed writer and sociopath, Pierre-François Lacenaire. Working with an accomplice, Lacenaire robbed and killed a petty criminal he knew from jail, along with the man’s mother. He was eventually caught and sentenced to death by guillotine.

Dostoevsky discovered an account of the murders decades later, translated it from French, and published it. Such criminal trials were, said Dostoevsky, “more exciting than all possible novels because they light up the dark sides of the human soul that art does not like to approach.” Maybe he was posing himself a challenge in those words.

In his treatment, Birmingham interweaves the stories of Lacenaire and Dostoevsky, shifting between the making of a murderous sociopath and the life of a writer.

The Lacenaire material is fascinating, down to his efforts to recruit a partner in crime. Where does one find such talent? Prison. Lacenaire committed a theft and began spreading news around town that he’d done it, awaiting arrest and imprisonment for the crime. Successfully behind bars, he began scouting for his future accomplice while learning everything about the underground he could.

Upon release he embarked on a series of criminal adventures, including the double murder. He was later captured after passing counterfeit bills. A dogged investigator assembled the evidence for a conviction.

Lacenaire dressed impeccably and attracted the amorous attention of women, even—especially—in prison awaiting the guillotine. “They sent him food and fine chocolate,” writes Birmingham. The public couldn’t get enough. “Newspapers and magazines published everything he wrote,” says Birmingham, “his poetry, his songs, a handful of letters, a vaudeville, a three-act play he composed in his school years.” Lacenaire wrote a paean to the guillotine calling it a machine of “sublime atonement” that purifies its victims in the “the bosom of nothingness.”

High-Stakes Gambling

Dostoevsky’s literary fortunes begun to turn with the success of Vremya and Notes from a Dead House, an autobiographical novel based on his years in exile. But just as swiftly, they turned again.

The Russian literary world was full of rivalries and partisanship. Dostoevsky was moving toward a more moderate political and social position, but tsarist conservatives found reason to attack him. When Dostoevsky published an article sympathetic to Polish insurrectionists in 1863, one conservative publisher, Mikhail Katkov, publicly accused him of disloyalty to Russia. The tsar took notice and banned Vremya from publication.

How would the Dostoevsky brothers manage their obligations to their subscribers? They started a second publication, but Epokha—Epoch—couldn’t escape the mounting debts necessary to start from scratch. Misfortunes multiplied. Dostoevsky’s tubercular wife succumbed to her illness, and then a few months later his brother and business partner died of an acute liver ailment.

Dostoevsky assumed his brother’s debts and tried keeping Epokha afloat but couldn’t. Loans were elusive, and he ran out of operating capital. Meanwhile, by 1865, debtors began calling his notes. He had no money to pay, and debtor’s prison wasn’t an option. The only way out was a publishing deal with an advance.

Unfortunately, the only publisher willing was a man named Stellovsky, who offered some of the worst terms imaginable. Says Birmingham,

Stellovsky would give Dostoevsky the three thousand rubles he needed in exchange for an edition of his collected works, but now he wanted the right to include any new material he would produce for the next three and a half years. He also wanted a new novel from Dostoevsky—a small one, mind you, a story of at least 160 pages—and he wanted it by November 1, 1866. Dostoevsky would do well to keep that date in mind because Stellovsky required one more brutal stipulation: if Dostoevsky failed to meet that deadline for his new novel. Stellovsky would own the right to publish anything Dostoevsky wrote for the next nine years—and he would pay Dostoevsky nothing.

Dostoevsky settled what debts he could, finagled a small loan from a writer’s association, and with just 175 rubles in his purse did the next most reasonable thing. He split for a German gambling town intent on expanding his meager fortunes at the roulette tables.

Against the Radicals

He lost everything, naturally. And in that place of total abasement, in need of more money and without options, he hit upon the idea for what would be his greatest novel to date.

Dostoevsky’s politics had taken a middle path between the old order and the progressives. The old order had squashed him, but the radicals occupied more of his worries. The prior year, he’d published a strange, short novel taking aim at the radical mindset. Notes from Underground met with mixed reactions, but it formed the basis for an insight.

The radicals, enthralled to an idea, were similar to Lacenaire who had fixated on the idea of murder. This was a period of radical foment with arson and violence flaring at random. The worldviews converged in the realization that human life was expendable for the cause, revolution, overturning the current order—or worse, sheer egoism.

“He would write a murderer’s story from the murderer’s perspective,” explains Birmingham. “How would he think?” It would expose the psychology of a single murderer, yes, but also point a mirror at the murderous impulse rising in Russian society. The trouble, as Birmingham says, is that publishers weren’t interested.

Dostoevsky had made enemies, and the journals weren’t inclined to serialize a novel that took at least partial aim at their own mastheads and readerships. Finally, however, the idea reached the same conservative publisher who had started his downward spiral, Mikhail Katkov. And he liked the idea. He liked it enough to advance Dostoevsky money for the first installment.

Everything about the story proved challenging for Dostoevsky: narrative details, the narrative voice, the whole thing. But he had a deadline and eager debtors and so plowed ahead.

The Other Deadline

When Crime and Punishment debuted in January 1866 the public was both shocked and excited. Nothing like it had appeared in print before. Dostoevsky was back, and readers wanted more. “My novel is an extraordinary success and has raised my reputation as a writer,” he wrote a correspondent in April.

Real-life events poured gas on the fire; an assassin attempted killing the tsar that same month, and the public drew comparisons between the assassin and Dostoevsky’s villain, Raskolnikov, as both stories unfolded simultaneously.

The problem was the other deadline—that little novel pledged to Stellovsky under his terrible contract. If Dostoevsky didn’t deliver the manuscript on time, all the success of Crime and Punishment would be for nothing. He somehow needed to keep up with the installments of Crime and Punishment while simultaneously writing Stellovsky’s novel. But progress on the little novel eluded him, and the deadline was just weeks away. What could he do?

Upon the advice of a friend, Dostoevsky hired a stenographer. Anna Grigorievna Snitkina eagerly took the job. Not only was her father a fan of Dostoevsky’s work, so was she. Dostoevsky imagined the little novel as the story of a gambler—based on his own unfortunate experiences. He would compose for several hours on his own, then dictate to Anna who would later prepare the draft. It took twenty-six days, but they did it—delivering Stellovsky’s manuscript in the nick of time.

The partnership was so successful Anna began working with Dostoevsky on the final chapters of Crime and Punishment. And the pair then began the biggest gamble of them all. Many years her senior, Dostoevsky proposed marriage. Anna accepted. In time, she became more than a wife; she was his creative partner, business partner, manager, and more. But Birmingham’s narrative stops before those later adventures.

Crime and Punishment, based on the story of a French sociopath, emerged in a moment of radical Russian upheaval and personal crisis, and persists as a classic of world literature.

Thanks for reading! I’m reviewing all the books I read in 2022, more or less, and sharing those reviews here, along with other bookish diversions. Sign up to discover more remarkable reading!

And if you’re already a subscriber, don’t keep it to yourself! Share it with someone who isn’t. Thanks!

Really enjoyed this!! Crime and Punishment was one of my favorite novels in high school but I haven’t revisited it since. You’ve inspired me to take it off my bookshelf.