Consult the Index: The Good Stuff Is in the Back

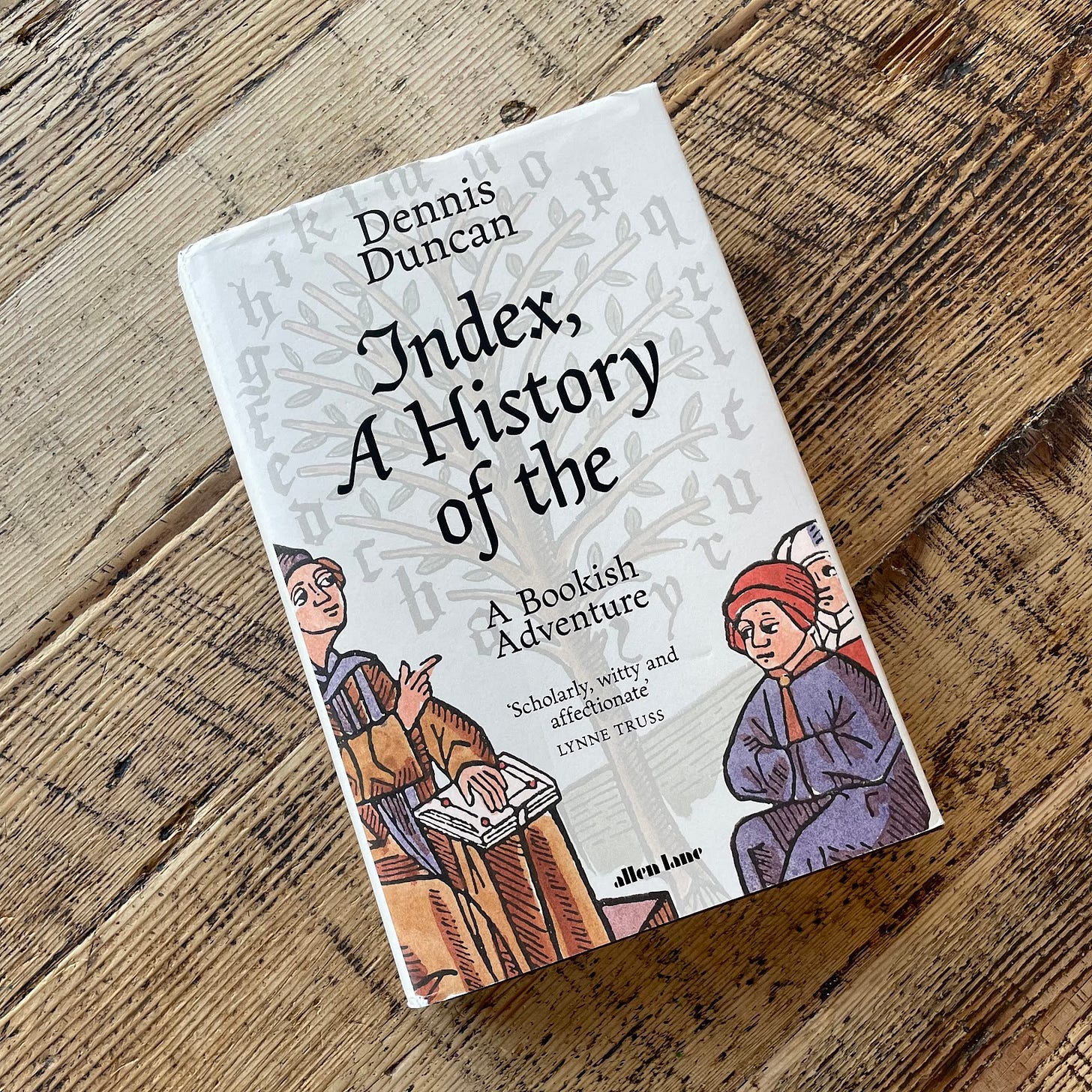

The Story of an Underrated Information Technology: Reviewing ‘Index, a History of the’ by Dennis Duncan

If an author wanted an index, they had to pay for it. That’s what the legal department said when I started as an editor at Thomas Nelson Publishers. And sure enough: It was right there in the boilerplate. The relevant paragraph in the contract said the author was responsible.

But that shouldn’t be, I said. As a reader, I knew an index was invaluable. As an editor, I wanted the books I worked on to have the best shot at being useful to readers. And in the days of casual bookstore browsing—remember those?—I also knew an index was a marketing tool. All that told me the publisher should pick up the tab.

Legal disagreed, but I persisted. I started loading the cost of an index into the production budget. If the publisher signed off on the cost, who could complain? Legal finally gave the nod. The index was on me.

“Once an idea has been generated,” says economist Tyler Cowen, “it can be used many times by many different people at very low marginal cost.” But, of course, that’s only true if those ideas can be found. For that you need an index.

We’re so familiar with this tail-end bit of book technology we might not realize it wasn’t always waiting for readers at the back, ready to point them to wherever they might want to travel within the volume. But, indeed, there was once a time—stave off the shudders—when the index did not exist.

So where did it come from? In his perfectly titled, Index, a History of the, author Dennis Duncan identifies its origins in the preaching and teaching needs of medieval monasteries and universities. By using alphabetical order, however, the index also represents a surprising break with medieval tradition.

Easy as A, B, C? Not really

The Middle Ages stand as a period of hierarchies—not only social hierarchies, but conceptual hierarchies. Medieval man “was an organiser, a codifier, a builder of systems,” said C.S. Lewis in The Discarded Image. “Distinction, definition, tabulation were his delight.” Along with that categorization came evaluation, rank, and emphasis.

Simple alphabetization undermined all that. It made every category of equal importance. Maybe worse, it could tend to emphasize subjects whose names appeared earlier in the alphabet over those that appeared later—prioritizing agriculture over theology, for instance, an arrangement no medieval intellectual would countenance.

Duncan quotes a pair of scholars who explain,

God had created a harmonious universe, its parts all linked to each other; it lay with the scholar to discern these rational connections—those of hierarchy, of chronology, of similarity and difference, etc.—and to reflect these in the structure of their writing. Alphabetical order implied the abdication of this responsibility.

Oh, well. Necessity often makes us challenge our assumptions, or at least find workarounds.

In the thirteenth century, Robert Grosseteste of Oxford needed some way to retrieve his learnings from his vast range of reading. He came up with an extensive table—an index—of all the subjects he encountered in classical and patristic texts. Grosseteste made himself an analog search engine. Duncan compares his index to “a Google on parchment that takes its subjects and explodes them across the whole of known literature.”

Around the same time in Paris, Hugh of Saint-Cher came up with his own table. But instead of ranging across many books, this index focused on just one. “Hugh,” says Duncan, “will be the first to produce a concordance to the Bible, to break the book down and rearrange it into an alphabetical index of its words.” The final version identified “over 10,000 terms and listed them in alphabetical order.” Duncan describes the concordance’s random access to the Bible as “wormholes . . . through the scriptures.”

The value of these and subsequent developments were widely recognized. Duncan mentions fees for compiling indexes showing up in papal records by the early fourteenth century.

People had been working on ways of atomizing the scriptures for easier consultation and study for ages. In the third century, Origen’s hexapla arranged multiple Old Testament versions in parallel columns for comparison. Inspired by Origen’s side-by-side arrangement, as well as work by Ammonius of Alexandria, Eusebius created his famous canon tables to facilitate comparison among parallel gospel passages. But it was not until the thirteenth century that Stephen Langton, the archbishop of Canterbury, inserted chapter numbers in biblical passages.

Verse numbers came 350 years later in the middle of the sixteenth century—a convenient time for innovation. By then, printing had revolutionized book production.

Coming of Print and the Page

All of the assumptions about book formatting we take for granted today were once the products of innovation and experimentation. Ordering a book by page number, essential to the index as it developed, seems obvious to us now. But just like alphabetical order, someone had to pioneer the idea.

Up till then, line, verse, and paragraph numbering schemes worked best. But print standardized the content of a page down to a single character; as a result, page numbers emerged as a viable way to divide a book’s contents. Marrying this new locator to the index transformed the use of texts.

Duncan quotes Conrad Gessner, a sixteenth century booster of indexes.

It is now generally accepted that copious and strictly alphabetically arranged indexes must be compiled, especially for large, complex volumes, and that they are the greatest convenience to scholars. . . . Truly it seems to me that, life being so short, indexes to books should be considered as absolutely necessary by those who are engaged in a variety of studies.

But Gessner also struck a note of concern.

Because of the carelessness of some who rely only on the indexes . . . and who do not read the complete text of their authors in their proper order and methodically, the quality of those books is in no way being impaired, because the excellence and practicality of things will by no means be diminished or blamed because they have been misused by ignorant or dishonest men.

Gessner was concerned people would shortcut real engagement with a book by scanning the index, jumping to a few interesting passages, and then acting as though they understand the whole, having read just a bit.

“These are Men who pretend to understand a Book,” said Jonathan Swift a couple centuries later, “by scouting thro’ the Index, as if a Traveller should go about to describe a Palace, when he had seen nothing but the Privy.”

The root of this concern, as Duncan points out, goes all the way back to Plato’s famous dialogue, Phaedrus, in which the god Theuth plumps his invention of writing. The king Thamus rejects Theuth’s claims. Writing, he says, will make people insufferable. Why? They’ll read, assume they understand things they don’t, and then prattle on like know-it-alls.

New information technologies, whether writing or the index—and the index is an information technology—always tend to unsettle because nobody is certain of the implications. Beneficial uses go underrated, while misuses are often overblown.

The Key to All Knowledge

The index’s full value only came into view over time and by persistent development. In the nineteenth century, priest and publisher Jacques-Paul Migne compiled and published a comprehensive collection of patristic texts in more than 200 volumes.

To help readers navigate the library, Migne capped the series with a massive four-volume index that arranged and sorted the content in dozens of ways. As Migne enthused,

Our Indexes have cleared the way; they have levelled mountains and straightened the most tortuous paths. . . . With the help of our Indexes, this vast subject has become small; distances have become shorter, the first and last volume come together. . . . What a timesaver! More than the railway, more even than the balloon, this is electricity!

Later that century, librarian J. Ashton Cross conceived of a “Universal Index of Knowledge” in which libraries all over creation would compile keyword indexes of their books and submit them to a master list for the consultation of the curious. Modern internet search engines rest on the model of these and other nineteenth century macro indexes.

In the end, Duncan’s Index, a History of the, lends the humble index the esteem it deserves as a critical tool of research and discovery, and also a map of a reader’s path through a book and how to find one’s way again.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related post:

All There Is to Know, More or Less

Alphabetical arrangement is an odd way to communicate information about the world. Why, for instance, should aardvark take precedence over atom, agriculture, astronomy, algebra, or autonomy—all of which seem more significant than a small nocturnal mammal?

Love learning about things I didn't realize interested me! "The index was on me." What an unusual achievement; from now on I will definitely regard the index of Thomas Nelson books through a different lens:)

What a curious path the book has travelled in development. I get most excited by a good bibliography. Here in the privacy of Substack, I’ll admit to being that reader who skips the text and starts immediately underlining books in the bibliography that might be of more interest.