Bookish Diversions: C.S. Lewis in Writing Hell

Derek Parfit’s Mad Dash, William Faulkner’s Wheelbarrow, Dean Koontz’s Nonexistent Outlines, More

The writing habits, methods, and struggles of writers are forever interesting. How do they tease all those words from the mind? What about the obstacles to creativity, or even simple completion?

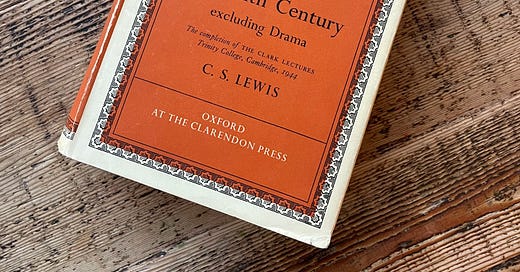

¶ O HELL. In 1935, C. S. Lewis agreed to contribute a book to the Oxford History of English Literature: English Literature in the Sixteenth Century, Excluding Drama. Interesting that the book formally excludes drama because that’s what marked its composition. It was a beast to complete, and Lewis didn’t finish until 1953—eighteen years after contracting to write the book.

The acronym of the Oxford series provided him just the joke he needed to capture how he felt about the project. “The O HELL lies like a nightmare on my chest,” he wrote one of the project editors, Frank Percy Wilson, in 1938. “I have a growing doubt I ought to be doing this.” Only three years in and he could already tell it would take him forever. He wondered if “there’s any chance of the world ending before the O HELL appears?”

Still, he soldiered on, year after year, working slowly through the library, writing, revising, amassing enough text for a nearly 700-page book. Some of it was delivered in “embryonic form,” as Lewis said, during a 1944 lecture series. Other parts required more creative means for their composition. He wrote some bits as individual papers on Renaissance authors which he then, according to biographer Alan Jacobs, graded as he might grade his students’ essays. Anything to stay creatively engaged.

Discouragement was a real challenge. He shared chapters of the book with the Inklings, a group of literary friends and critics, such as J. R. R. Tolkien, Owen Barfield, and Hugo Dyson. Tolkien evidently savaged a passage in 1948. In his biography of Lewis, A. N. Wilson speculates Tolkien’s judgement “reduced [Lewis] to visible signs of grief—perhaps to tears.” Whatever transpired, it was rough enough that Tolkien backtracked in a letter of apology. “And let me beg of you,” he said, “to bring out OHEL with no coyness.”

While Lewis struggled with O HELL, he was nonetheless remarkably prolific. “By my unscientific estimate,” writes Jacobs in The Narnian, “during the period from 1949 to 1955 Lewis wrote, and published, about 600,000 words of prose. . . . The Narnia tales alone contain more than 400,000 words.” This estimate excludes O HELL, Jacobs explains,

because it is hard to know how much of it he had already written before 1949 rolled around, but given that he took a leave from his academic duties in 1951 and 1952 to finish the book, it is possible that we should add another 100,000 words or so to the stack.

A hundred thousand words is a book unto itself. The idea that Lewis ground out that much prose to finish a partially completed book neither he nor his friends enjoyed while simultaneously working on other projects is mind-boggling. And Jacobs notes that Lewis maintained this sort of output while his confidence in his own abilities waned. “I feel my zeal for writing, and whatever talent I originally possessed, to be decreasing,” he wrote in 1949. “Nor (I believe) do I please my readers as I used to.”

Despite the “interminable labor,” Jacobs counts O HELL as “the greatest of all of Lewis’s books.” He’s not alone in that assessment. While some noted his idiosyncratic opinions, the book was generally well received. “In spite of its lacunae and eccentricities,” says Wilson, “the OHEL volume established Lewis beyond question as a giant among the pygmies of the Oxford English Faculty.” It even secured him a professorship at rival Cambridge the same year it was published.

Seventy years later, the book remains fascinating and enjoyable one page to the next—so much so that HarperCollins has recently reissued the fruit of that “interminable labor” in a brand new edition.

¶ Writing a book.

It’s like being an ant crossing the road.

¶ Living under a deadline. Hustling for an academic appointment, philosopher Derek Parfit had to deliver a book. His biographer David Edmonds describes the mad sprint to the finish. It was the summer of 1981, and, working backward from his next opportunity to apply for the position, Parfit figured he had just over a year and a half to deliver the manuscript.

The project, says Edmonds,

would occupy almost every waking hour of almost every day. . . . He began to develop some distinctive habits. In toothbrushing, for example: teeth had to be cleaned, but that was no reason for philosophy to stop. Parfit was an enthusiastic and comprehensive tooth-brusher; no incisor, canine or molar was neglected. Toothbrushing took up more of his time than eating. . . . During one toothbrushing session he could read 50 pages.

He had the same attitude to staying fit. The exercise bike was philosophy-compliant; it was perfectly possible to combine cycling and reading. . . . Clothes, food and drink were more problematic, but Parfit devoted as little time to them as possible. He wore the same outfit every day—grey suit, white shirt, red tie—so that there was no time-wasting and energy-sapping decision to be made each morning. He drank coffee, but boiling a kettle became an unnecessary luxury; so he would throw a dollop of instant coffee into a mug, and fill it with hot water from the tap. Sometimes, cold water would do. The caffeine was what mattered. . . .

Parfit’s personal papers contain evidence of the scramble to the finish line. He dispatched the book to Oxford University Press (OUP) chapter by chapter. By the final week, in the autumn of 1983, Parfit was on the brink of a breakdown. He was up all night every night, before seeking some pill- and alcohol-induced rest.

Amazingly, he finished on time. Also amazing, the book, Reasons and Persons, became a surprise bestseller—“OUP’s bestselling academic philosophy title of the past 50 years,” says Edmonds, “and perhaps ever.”

¶ Between me and the work. William Faulkner’s problem was he could rarely get to the writing, at least early on. The demands of making a living stood between him and the work he actually wanted to do. In one of his ill-fated jobs, Faulkner served as postmaster for the University of Mississippi post office, though it’s hard to say he actually worked at the job.

“Faulkner would open and close the office whenever he felt like it, he would read other people’s magazines, he would throw out any mail he thought unimportant, he would play cards with his friends or write in the back while patrons waited out front,” says Emily Temple. Novelist Eudora Welty described a typical experience:

We’ve come up to the stamp window to buy a 2-cent stamp, but we see nobody there. We knock and then we pound, and then we pound again and there’s not a sound back there. So we holler his name, and at last here he is. William Faulkner. We interrupted him. . . . When he should have been putting up the mail and selling stamps at the window up front, he was out of sight in the back writing lyric poems.

He managed to keep the job for a few years, but eventually drew the ire of his superiors and resigned. “I will be damned if I propose to be at the beck and call of every itinerant scoundrel who has two cents to invest in a postage stamp,” he wrote. (Temple’s treatment is, by the way, hilarious and worth reading in full.)

The trouble was, of course, that Faulkner still needed to make a living, and lyric poems weren’t paying the rent. Nor were his novels. He’d published three by 1929, but the newly married writer had yet to make any real money writing. Instead, he went to work at the local power plant, working through the night. “I shoveled coal from the bunker into a wheelbarrow and wheeled it in and dumped it where the fireman could put it into the boiler,” Faulkner recalled.

Shoveling coal seems hardly conducive to a writing life, but Faulkner made it work. The need for power would dip after midnight, and Faulkner could turn his attentions to the work he loved most. In October 1929, five years after quitting the post office, he started a new novel. Says Faulkner studies professor Jay Watson,

Using a wheelbarrow as a table—“just beyond a wall from where a dynamo [electrical generator] ran”—he would work on the manuscript “between 12 and 4,” until electricity use would pick up.

In only six weeks, he completed the entire manuscript, which he titled “As I Lay Dying.”

Watson continues, “The novel, along with The Sound and the Fury, which was published later that fall, would establish Faulkner’s reputation as a modernist master.”

¶ Scary productive. “I was the son of the town drunk,” recalls thriller writer Dean Koontz. “Where did the storytelling come from?” If you could get to the bottom of that question, you might have the secret to writerly productivity. Karen Heller has come close, publishing a fascinating profile of Koontz earlier this week in the Washington Post.

“When the writing is working, nothing stops me,” says Koontz. He works ten hours a day, six days a week, and edits as he goes—something writers are often discouraged from doing. It hasn’t harmed his output. Koontz has written more then a 110 books and adds two more to the pile each year. Says Heller,

Koontz prohibits distractions. He doesn’t read emails—his assistant or his wife, Gerda, print them out—and won’t open a browser, even to check facts or the news.

“I never go online. Never. I don’t trust myself,” he says. “I know I’m a potential obsessive, and I don’t want to waste time.” Head down, nose to keyboard.

Jessica Tribble Wells, executive editor of Amazon Publishing, describes Koontz as an anomaly. “I’ve never known him to have writer’s block,” she says. Once he plugs into a story, he just keeps going. Heller notes that Koontz works without outlines. “He feels they’re constraining.” Instead, Koontz says, “I give the characters free will. . . . The novel becomes organic and unpredictable and much more interesting to me.”

You might be right in thinking such a regimen sounds grueling and impossible to maintain. Koontz admits there are days he thinks, “I can’t do this anymore.” But he also says, “I don’t know who I’d be if I wasn’t writing.” Read the rest of Heller’s piece for a glimpse of Koontz’s extraordinary life—and his nearly 30,000 volume personal library.

¶ Writing like jazz. Novelist Haruki Murakami also works without outlines. His secret? Come what may, he aims to produce 1,600 words a day. Addressing the opinion that such an approach is too factory-like, he simply asks, “Why not write in whatever way is most natural to you?” And, despite his strict quota, the way he describes his style is anything but factory-like. “I wrote as if I were performing a piece of music,” he says.

Jazz was my main inspiration. As you know, the most important aspect of a jazz performance is rhythm. You have to sustain a solid rhythm from start to finish—when you fail, people stop listening. The next most important element is the chords, or harmony if you like. . . . There are so many kinds. Though everyone is using a piano with the same eighty-eight keys, the sound varies to an amazing degree depending on who’s playing. This says something important about novel writing as well. The possibilities are limitless—or virtually limitless—even if we use the same limited material.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Which of the Koontz novels would you recommend to a beginner?

I didn’t know that about Faulkner’s job shoveling coal. Thanks for writing!