Cormac McCarthy’s Sideline: Freelance Copy Editor

The Pulitzer-Winning Novelist Enjoyed Helping Academics Clean up Their Work

When Cormac McCarthy died last year, critics, scholars, and fans alike weighed in on the qualities they found most distinctive in his books. Time and again they mentioned his style. Whether the long, sweeping passages of Blood Meridian or the staccato bursts of The Road, McCarthy’s approach was unified by an elegant minimalism most evident in, of all things, his punctuation.

A Man with Opinions

McCarthy followed several self-imposed rules, distilled here by Josh Jones from one of the Pulitzer-winning novelist’s rare interviews. The first is recognizable by the quotation marks absent from his dialogue; he eschewed them. Same with the semicolon I just used and exclamation points. “There is no place in English literature for either,” he said.

“I believe in periods, in capitals, in the occasional comma, and that’s it,” said McCarthy. A scan of his books reveals additional use of question marks and em dashes—even the rare semicolon and exclamation mark(!)—but McCarthy’s punctuation was sparse by any measure.

A fascinating study by Adam Calhoun compared the marks employed by various writers by removing all the words between them. Here’s how McCarthy’s punctuation in Blood Meridian stacks up against William Faulkner’s in Absalom, Absalom!

And it’s not just the type of punctuation employed. It’s also the frequency, seen by comparing the number of words per punctuation. Whereas Faulkner uses eight words before dropping in a comma, semicolon, or dash, McCarthy uses twelve by Calhoun’s count—fifty percent more words per mark.

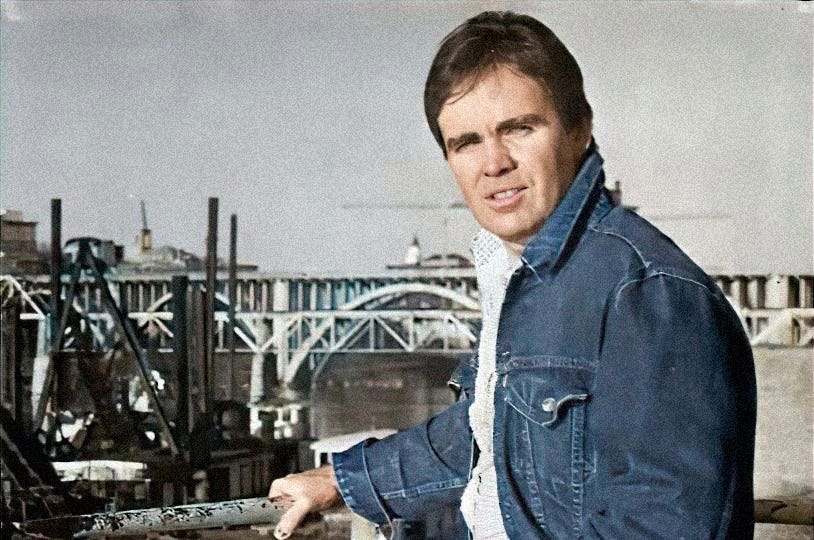

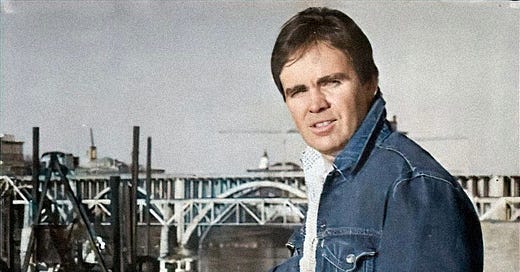

This is the work of a man with firm feelings about how to punctuate one’s prose. As film director Richard Pearce once said, “He is absolutely at peace with his own rhythms and has complete confidence in his own powers.” That’s evident on the page. What’s less obvious? His subtle evangelism for his opinions, occasionally manifested by lending his editorial aid to other writers.

An Early Foray

At first that might sound odd. McCarthy didn’t hang out with other writers. He preferred the company of scientists and actually moved to New Mexico to be close to the Santa Fe Institute, a multidisciplinary think tank. “I’m here because I like science, and this is a fun place to spend time,” he told Newsweek journalist Nick Romeo in 2012. He joined the board of trustees and kept an office there among the physicists, mathematicians, biologists, archeologists, anthropologists, and economists.

It was for one of those economists McCarthy offered his editorial services in 1996, maybe for the first time. W. Brian Arthur was a fellow at the institute and had written an article on a new theory called increasing returns for Harvard Business Review. Arthur sent a draft to McCarthy and later called to see what he thought.

“Would you be interested in some editing help on that?” McCarthy responded. Arthur said yes, and the pair spent four days reworking the piece the next time they were together.

“He took apart every single sentence, deleted every comma he could find,” Arthur told Rick Tetzeli at Fast Company, adding,

The word got back to my editor at Harvard Business Review. She called me up, in a slight panic, and says, “I heard your article’s getting completely rewritten.” And I said, “Yeah!” She says, “By Cormac McCarthy? What did he do to it?” And I said, “Oh, well, you know, pretty much what you’d expect. It now starts out with two guys on horseback in Texas, and they go off and discover increasing returns.” And for a couple of seconds she was aghast.

Of course, Arthur only teased. McCarthy helped the economist better state his case, and the article went on to become one of the most influential the Review ever published. “The theory of increasing returns is as important as ever,” says Tetzeli. “It’s at the heart of the success of companies such as Google, Facebook, Uber, Amazon, and Airbnb.”

Smoothing the Prose

McCarthy continued to edit papers and books for scientists orbiting around the institute for the next couple of decades. When McCarthy heard about theoretical physicist Lisa Randall‘s first book, Warped Passages, then only in manuscript, he asked to read a draft. For an author who banged out almost everything he ever wrote on a typewriter, McCarthy naturally worked in hard copy.

“I got the manuscript back in the mail, and it was marked up on every page,” Randall told Rolling Stone writer David Kushner. “He read everything. He essentially copy edited it, getting rid of some of my semicolons, which he really didn’t like.” McCarthy noted all the offending marks in the margins; from there Randall purged them. And McCarthy gored other glyphs as well.

“Apparently exclamation points are only for exclamations!” Randall told Jennifer Schuessler, a New York Times reporter intrigued to hear McCarthy had edited the book. “He really smoothed the prose.” Warped Passages became a bestseller.

McCarthy worked on Randall’s second book as well, Knocking on Heaven’s Door, also a bestseller, and continued to offer his services to others. When he read physicist and cosmologist Lawrence Krauss’s biography of Richard Feynman, Quantum Man, in hardcover McCarthy loved it—or nearly did. “I think the book is almost perfect,” he told Krauss. “Would you let me copyedit the paperback and make it perfect?”

The process sounds similar to McCarthy’s work with Randall. Recalled Krauss, “He made me promise he could excise all exclamation points and semicolons, both of which he said have no place in literature.” McCarthy then “went through the book in detail and made suggestions for rephrasing in certain points as well.” The paperback of Quantum Man reflects all those edits.

Clarity of Thought and Expression

If all this emphasis on punctuation sounds pedantic, it shouldn’t. McCarthy’s true obsession was science. “We had some nice conversations about the material,” said Randall when reflecting on her work with McCarthy. His colleagues at the Santa Fe Institute all mentioned how engaged he was in conversations across their various disciplines, able to keep up and contribute at a surprising level for a nonprofessional.

This deep and thorough engagement bears directly on his editorial eye. It’s all about clarity of thinking and expression. “Science is very rigorous,” he told Kushner. “When you hang out with scientists and see how they think, you can’t do so without developing a respect for it. And part of what you respect is their rigor. When you say something, it needs to be right.”1

To that end, in 2018 McCarthy worked with Van Savage at the institute to distill his writing and editing advice down to a list of bullet points; the two had collaborated on Savage’s papers since the biologist first arrived at the institute in 2000. The journal Nature published the list, supplemented by input from another biologist, Pamela Yeh.

The first item on the list sets the tone for the remaining sixteen. “Use minimalism to achieve clarity,” they write, a statement that could double as a summary of McCarthy’s total literary approach. Another point they stress: the adventure of wrestling with big ideas and expressing them: “Just enjoy writing,” they say. “Try to write the best version of your paper. . . . You can’t please an anonymous reader, but you should be able to please yourself.”

This goes back to what McCarthy saw as a fundamental overlap between science and writing, something he told Nick Romeo. “Both,” he said, “involve curiosity, taking risks, thinking in an adventurous manner, and being willing to say something 9/10ths of people will say is wrong.”

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

While his focus was science, McCarthy didn’t always limit his editorial assistance to scientists. He developed a bit of a friendship with David Kushner, the writer for Rolling Stone, and offered to give his prose a workover as well. “When I got up the nerve to send him a draft of a story I was working on,” said Kushner, “he proved a gracious but exacting editor, stripping my work of the commas he used so economically in his own writing.”

Reading Cormac McCarthy initially sends my brain into a tizzy! As our bodies need to acclimate to the gentle rhythm when adrift at sea, our minds have grown accustomed to the standard punctuation rules to hold the words and phrases in their proper places, which makes his writing feel like a swaying boat. After a few chapters, the flow is so natural it's hardly noticeable. It's getting off the boat and walking on stable ground (reading any other author), which then feels disorienting. His bravery and creativity are incredible.

How fascinating. That degree of confidence astonishes me. My favorite aspect of this piece is the intellectual generosity of helping others craft the best and most compelling expression of their ideas. His multidisciplinary curiosity is also beautiful. Thanks for the vivid visual of McCarthy’s punctuation versus Faulkner’s. If this comment feels staccato it’s because I’m trying very hard not to use commas. 🙂