Pinocchio Was an Insufferable Brat—and Also Like Jesus

The Tricky Business of Becoming Fully Human. Reviewing ‘The Adventures of Pinocchio’ by Carlo Collodi

If you’re mainly familiar with the character Pinocchio from the 1940 Disney movie, chances are good nothing will prepare you for the moment in Carlo Collodi’s original novel when the raging puppet throws a mallet at the Talking Cricket and kills the insect for offering unwelcome advice.

“I’m warning you, you awful, gloomy Cricket,” says Pinocchio in John Hooper and Anna Kraczyna’s new translation of The Adventures of Pinocchio. But the Cricket keeps yammering, and Pinocchio lets fly. “So the poor Cricket had barely enough breath to go ‘chirp-chirp-chirp’ and then it was left there—stone dead, stuck to the wall.”

In the Disney movie, Jiminy Cricket doubles as narrator and Pinocchio’s conscience. In Collodi’s novel, he’s smashed after barely a dozen pages. That’s far from the only difference. There is, for instance, the moment the puppet gets lynched from an oak tree and dies while two scoundrels try stealing four gold coins stashed in his mouth.

And that’s how the story ends. At least, at first.

You’d Better Go to School!

Collodi, an Italian journalist, published the novel chapter by chapter in a new journal called Newspaper for Children from July to October 1891. Reformers were working to improve education across the country, and Collodi intended to his story to encourage the effort.

Born poor but given the lucky chance to attend school, Collodi knew how disagreeable education could be. His nephew reported that Collodi often ran away from home when young, and Collodi admitted to being a difficult and disruptive student until he turned twelve. Autobiography winks through The Story of a Puppet, as Collodi’s serial installments were first known.

What triggered Pinocchio’s homicidal rage? The Cricket, upon hearing Pinocchio’s plan to run away and skip school, asks, “Don’t you know that, by acting that way, you’re bound to grow up to be an absolute donkey and that everyone will make a fool out of you?”

Silencing a warning doesn’t make it untrue, of course, and ten chapters later Pinocchio is dangling at the end of a rope—all because the willful brat refused to go to school. But by then Collodi’s readers, both old and young, were invested in the story and hoped for a more redemptive ending.

Pinocchio is literally a blockhead and yet oddly lovable. Readers wanted to see him reunited with his father—the impoverished woodworker, Geppetto, who sold his only coat to buy a textbook Pinocchio traded for a ticket to a puppet show. They hoped to see Pinocchio repent of his juvenile ways and become a responsible young man, worthy of his father’s affection.

Collodi listened and resumed writing.

An Absolute Donkey

The story follows an episodic path with little narrative structure, save a few persistent and competing desires of our protagonist that drive the plot forward:

reuniting with his father, who’s traveled abroad looking for his runaway son;

growing up and becoming a human, which will require—argh!—going to school;

pleasing the long-suffering Blue-haired Fairy, who resuscitates, adopts, and protects him; and

following his own stupid whims and fancies, which plunge Pinocchio into more trouble than Collodi could keep straight (details get away from him and conflict in places).

A pair of episodes captures all four of these desires in action. At the behest of the Fairy, Pinocchio finally returns to school and applies himself to his studies. But ne’er-do-well friends urge him to skip class and see a giant shark swimming the nearby coast. Pinocchio can’t help himself. His father had been lost at sea. He’d seen the shark in the vicinity when Geppetto’s boat went under, and the Fairy assured him they’d meet again. Maybe this was his chance.

It wasn’t. An argument breaks out and the kids turn on Pinocchio, lobbing their schoolbooks until one boy is struck in the head. Pinocchio narrowly avoids jail, runs away, and almost ends up devoured by a monster before returning home to the Fairy.

In the second episode, Pinocchio promises the Fairy to redouble his efforts at school, and she promises he’ll become a real boy. But then the day before the transformation, Pinocchio’s friend Lampwick tells him he’s running away to the magical country of Playland. “There are no schools there,” says Lampwick. “There are no teachers there. There are no books there. In that blessed land you never study.”

Pinocchio resists the temptation but finally succumbs at the last moment, and—despite the Fairy’s promise of his becoming a real boy—chooses a life of ease over responsibility. You already know what happens; the Cricket was right. After several months of bliss, Pinocchio actually turns into “an absolute donkey” and is sold to a circus where he’s lamed and then sold again—this time to a man who wants to turn his hide into a drum.

Fortunately for Pinocchio, the Fairy locates and rescues him in time.

Jesus, Mary, and Joseph!

The Blue-haired Fairy presents an interesting figure. First introduced as the ghost of a little girl with blue hair who meets Pinocchio right before he’s hanged, she transforms into the loving Fairy who takes a motherly role once the puppet is restored to life.

There’s good reason to think she’s patterned after the Virgin Mary. First, consider her blue mantel of hair. Christian iconography typically depicts Mary wearing blue; it signals divine adornment. Next, she often comes to Pinocchio’s aid and leads him in his improbable progression toward maturity.

And there are other associations. Collodi named the puppet’s father Geppetto—an Italian form of Joseph. And Pinocchio takes on Christlike characteristics, none more striking than when he’s hanging from the tree.

At that point, close to death, he remembered his poor dad, and stammered:

“Oh, Dad! If only you were here! . . .”

And he didn’t have the breath to say more. He closed his eyes, opened his mouth, stiffened his legs, gave a big shudder, and remained there, as if completely rigid.

Pinocchio’s statement parallels Jesus’s cry of dereliction on the cross: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me.” Ditto with the detail about lacking the breath to say more and giving a shudder: “And Jesus uttered a loud cry, and breathed his last.”

As translators, Hooper and Kraczyna point out an additional linguistic parallel from the original Italian: “Equally striking is that Pinocchio calls for the help of his ‘father,’ Geppetto, using the familiar form of ‘you,’ tu. Previously, he has always addressed the carpenter using voi. In the Italian translation of the invocation above, Jesus also uses tu.”

And we can push this idea even further.

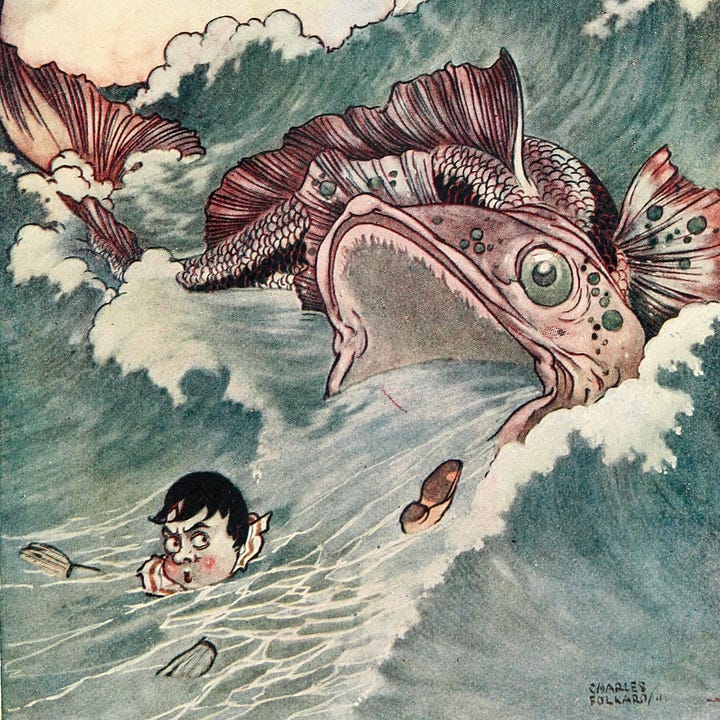

Swallowed by a Fish

In the Gospels, Jesus compares his impending death and resurrection to the story of Jonah, who was famously swallowed by a giant fish. “As Jonah was three days and three nights in the belly of the whale,” he says, “so will the Son of man be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth.” In Christian iconography, Death is often depicted as a giant monster who holds humanity in its jaws. In an event known as the Harrowing of Hell, Christ descends to Death following his crucifixion and liberates humanity before his resurrection and ultimate triumph.

Place that alongside Collodi’s narrative. Lost at sea, Geppetto is swallowed by a giant shark. Like Pinocchio at the end of the rope, he’s dead—and yet not. Pinocchio finds himself swallowed by the same shark. Once inside, he locates Geppetto and frees him.

Despite his father’s fear and setbacks along the way, Pinocchio overcomes the difficulty and rescues Geppetto from the jaws of death—a resurrection of sorts. And it is at this point, comment Hooper and Kraczyna, “Pinocchio goes from being a child to being an adult. He is no longer someone in need of protection, but rather a protector.”

He also becomes fully human.

Becoming Fully Human

Walt Disney made a movie. It’s a classic. But his story only vaguely resembles Collodi’s book, published in its final form in 1893. Pinocchio’s nose, for instance, doesn’t grow with every lie. It’s less consistent and more mysterious than that. Yes, the story is moralistic and even heavy-handed in places, but the original is for Italian literature what Don Quixote is for Spanish. That is, in part, because Pinocchio is utterly relatable—likely, even if you’re not prone to skipping school and dodging your duties.

I saw myself in Pinocchio to sometimes unsettling and embarrassing degrees. It’s a humbling reminder at the start of Lent to think of how often I whack the Cricket advising me for my good. And it’s a hopeful reminder that Lent ends in Easter, resurrection, and all it entails. Becoming fully human is, as Pinocchio discovered, tricky business—though possible with help.

I had no idea what to expect when adding The Adventures of Pinocchio to my classic novel challenge for 2023. It came as a recommendation from a friend. I’m glad. As with Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, I found it worthwhile and enjoyable. I also found it curious I ended up choosing two fantastical books of protomagical realism for back-to-back months.

Next month, I venture into something decidedly more realistic, at least ostensibly: Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. If you know anyone who’d appreciate this review or my upcoming review of Pride and Prejudice, feel free to share this post and recommend they subscribe. And let me know your thoughts in the comments below.

Thank you for reading! Please share Miller’s Book Review 📚 with a friend.

If you’re not a subscriber, take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

The minute the cricket got smashed I knew this was the book for me!!

I first read this book a couple years ago and was blown away. I was curious what you’d think. Enjoyed your thoughts and the insights from the edition you read. Thanks for sharing.