The Cult of Authenticity: Life in the 1990s

Grunge, the Internet, and the Dotted Line to Right Now. Reviewing ‘The Nineties’ by Chuck Klosterman

If my current self could go back to my teenage self and tell me that Sir Mix-a-Lot would remix his only Billboard-charting song, “Baby Got Back,” to sell Chex Mix in a 2023 Super Bowl commercial, I wouldn’t have believed it. Same thing when Sarah McLachlan appeared, using both her music and wildlife advocacy to sell Busch Beer.

Back then, rappers would trade insults, fists, and sometimes more dangerous projectiles over who appeared to have sold out. And McLachlan was high priestess of a kind of music that deified authenticity and feeling.

Why couldn’t MC Hammer quit? Because he was “too legit,” a concept that somehow made sense in 1991. Meanwhile, fakers were good for two things: a moment of ridicule and a lifetime of dismissal. Remember Milli Vanilli? Neither does anyone else, except as scapegoats for the sin of lip-syncing their music and our gullibility in going along with the mime. Whole universe, you know it’s true.

Sincerity Is All

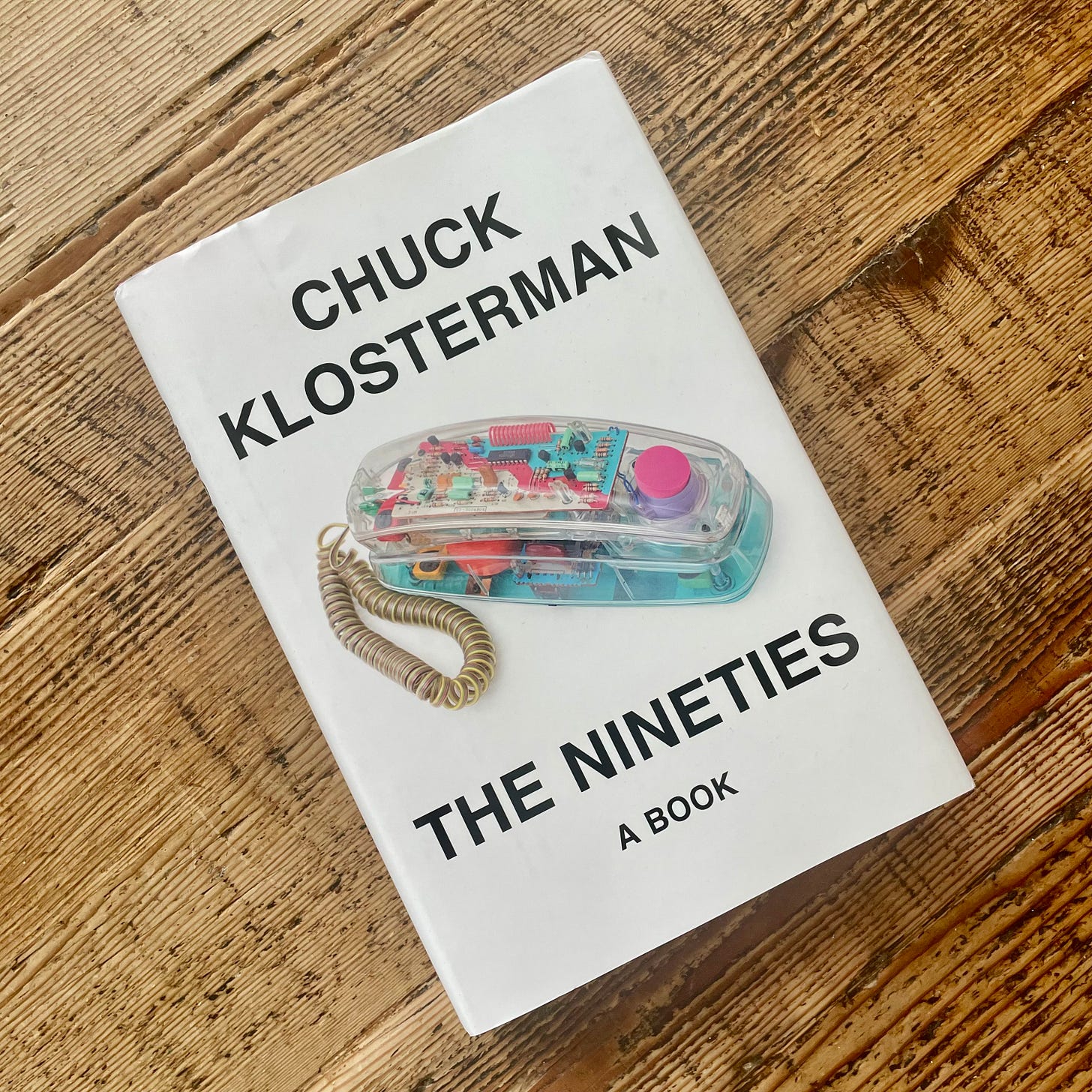

A decade is an arbitrary thing, but when meaning-hungry humans scan a particular stretch of time, we can create narratives and meanings particular to the period. Popular cultural critic Chuck Klosterman offers his novel take on the titular times in his retrospective, The Nineties.

The 1990s were a great decade for cults: David Koresh and the Branch Davidians, Heaven’s Gate and the Hale-Bopp comet, and the sarin gassers of Aum Shinrikyo. But anyone then alive, especially if young, had a good chance of induction into the Cult of Authenticity.

Some concern with authenticity has, of course, always mattered. But after a period of 1980s plastic and synthesizers, not to mention supposed Wall Street greed and political scandal—think: Iran-Contra—Americans were ready to double down on anything simple, true, genuine, and sincere. Even if it wasn’t.

What made artists worth listening to in the 1990s was their commitment to their craft, the honesty of their music. If we would have known they would sell out their integrity thirty years down the road, we would have punched eject on the tape deck and never looked back.

It’s curious to imagine the disconnect between attitudes today and three decades ago. We tend, as Klosterman says, to judge the past by present values. Nowadays we watch Mix-a-Lot and McLachlan and laugh. No harm, no foul. But back then trading on their reputations would have been seen as betrayal.

The Inflection Point

The 1990s, like any decade, was filled with events: the end of the Cold War, the first Gulf War, the terrorist bombing of the World Trade Center, and so on. Klosterman, only tangentially interested in such happenings as events, seems more focused on what our reactions to those happenings reveal about our assumptions and values at the time. He’s trying to excavate what people—mostly those in the dominate, white, middle-class culture of the time—felt and believed.

So, rather than begin the decade with the fall of the Berlin Wall, as many do, Klosterman keys the inaugural moment to the release of grunge band Nirvana’s Nevermind. It is, he says, “the inflection point where one style of western culture ends and another begins. . . .” The fact that frontman Kurt Cobain ended his own life a few years later somehow only validated his art.

If you wanted to be taken seriously in the 1990s, you had to be completely sincere. But wanting to be taken seriously might be evidence you weren’t. Wanting much of anything was suspect. There was in the period “an adversarial relationship with the unseemliness of trying too hard,” says Klosterman. “Any explicit desire for approval was enough to prove you were terrible.”1

In an age of Instagram influencers where it seems everyone either has—or is—a brand, this state of affairs is almost impossible to imagine. But, of course, this was before the internet refashioned our relationship to media.

The world was read-only in the 1990s. Broadcast television was at its zenith. Shows like Seinfeld or Friends had tens of millions of viewers—but so did just about any and every other sitcom, no matter how terrible. The success of a show depended on its time slot, not its content. Audiences were passive recipients of network programmers and advertisers.

That dynamic went for other media as well, particularly news and commentary. Gatekeepers determined both message and the messenger. By the late nineties the internet had already undercut that dynamic. Not only did chat rooms provide space for alternative conversations, but low-cost publishing options presented traditional media viable competition for attention and allegiance.

Combined with the sincerity-is-everything ethos of the period, blogging was inevitable. Ultimately, so was today’s influencer culture. As people saw that sincerity sells, it didn’t take long for social media platforms to transform authenticity into currency—even if it’s counterfeit.

It’s possible to trace the dotted line from yesterday’s authenticity obsession to today’s New Age-inflected wellness culture, alternative facts, conspiracy mongering, and choose-your-own-adventure takes on reality. Instead of listening to Art Bell’s Coast to Coast, we’re now living inside Art Bell’s Coast to Coast.

Potential for Betrayal

Klosterman’s approach can’t cover everything; beside the occasional vignette the black experience is, for instance, largely overlooked in his narrative. Still, it’s remarkably flexible and explains reactions to everything from the Major League Baseball strike and later steroid scandal to the presidency of Bill Clinton.

The public’s willingness to tolerate selling out depended on the potential scope of the betrayal. No one faulted the Eagles for charging $125 a ticket for their Hell Freezes Over tour—five times the national average. “The Eagles did not possess the potential to sell out,” says Klosterman; they were already as commercial as you could get. But fans would have crucified Fugazi had the punk band tried charging more than $5 at the time.

The same dynamic helped Clinton survive his scandals. Clinton, who was happy to admit his underwear preferences on MTV, played the authenticity card better than anyone. When he found himself embroiled in scandal, half the electorate expected nothing different and the other half cheered his refusal to back down.

Working under different values today, we don’t blink at Fugazi’s present ticket prices, anymore than we delete Sir Mix-a-Lot and Sarah McLachlan from our Spotify for bastardizing their own music.

“Times change, because,” says Klosterman, “that’s what times do.” Yet there’s a trajectory to the evolution. And traveling through 1990s authenticity culture provides an intriguing and entertaining explanation for how we got to now.

Thank you for reading! Please share Miller’s Book Review 📚 with a friend.

If you’re not a subscriber, take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-15 quotes about books and reading. Thanks, again!

Hence the joke of Todd Snider’s “Talking Seattle Grunge Rock Blues.” It’s also why the listening public was ambivalent about Alanis Morrissette. “She was successful because of her honesty,” says Klosterman, “but anyone that successful had to be lying.”

Amazing. It's funny that the 90's are all 72 degrees and fluorescent lights for me: started med school in '91 and then did 6 years of neurosurgery residency. So I don't recall music other than what my professors played in the OR and books other than Apuzzo's "Brain Surgery" and other riveting classics!

Yet another book I have to add to my must read list! I was only a small child in the 1990s but it’s my intention to do some research on different topics of the 90s one day. There’s a lot of things I miss from back then... including the end of pay phones for the most part! I have some odd obsession with them, even though I’ve never actually used one.