Chickens? A Bigger Deal Than You’d Guess

Birds in Books: Chick Lit, Plus Sy Montgomery’s ‘What the Chicken Knows’ and Charles Willeford’s ‘Cockfighter’

At any given moment, chickens outnumber humans on this planet four to one. Of course, we eat a lot of those birds moment to moment, so the global chicken population over the course of a year is actually quite a bit larger; back of the napkin math tells me it’s about 180 billion birds, maybe more. A lot of those end up in fryers. The lucky ones end up in books.

Naturally, my mind instantly jumps to Charles Portis’s 1966 comic masterpiece Norwood and Joann the Wonder Hen.

Chick Lit

Pacing her narrow cage “wearing a tiny scholar’s mortarboard on her head with a rubber band holding it in place,” Joann can supposedly answer any yes or no question by yanking a contraption in her pen. Her answers fail to impress, but our titular hero ends up hauling Joann around on his many adventures.

Chickens feature in many such literary adventures. Sometimes they scratch around the edges of the action, incidental details in the lives of the characters. Other times they play more significant roles. In Little House in the Big Woods, Laura and Mary “helped [Ma] weed the garden, and they helped her feed the calves and the hens. They gathered the eggs, and they helped make cheese.”

In Willa Cather’s My Ántonia, chickens play a role in family survival on the prairie. “Hens are a good thing to have, no matter what you don’t have,” says Jim Burden’s grandmother. The useful birds make more than a dozen appearances in the novel.

Meanwhile, the entire plot of David Benioff’s City of Thieves revolves around the quest for a dozen eggs. During the Nazi siege of Leningrad, young Lev is arrested for looting. While the crime warrants death, the local commander of the Soviet secret police gives him and a deserter named Kolya an out; if the pair can scrounge up the eggs necessary to make a wedding cake for the commander’s daughter, they live. No problem, right?

Wrong. Thanks to the Nazis, there’s no food around. Lev and Kolya must scour the city for the eggs, endangering their lives at every turn. When they finally find a chicken, they’re elated. “You think she can lay a dozen by Thursday?” Kolya asks. Not likely; turns out the bird is a rooster.

“You’re saying she won’t lay eggs?” Kolya asks.

“It’s a he,” the man responds. “And the odds aren’t good.”

With no other options, Lev and Kolya sneak out behind enemy lines where they end up in a high-stakes chess match with a Nazi commander, gambling for their lives—and one dozen precious eggs. I won’t spoil it for you.

If you’re looking for more such examples, writer, actor, and photographer Lisa Jane Persky maintains (though sadly no longer updates) a Tumblr called Chickens in Literature. There you’ll find George Orwell’s hens in Animal Farm who temporarily go on strike when the pig Napoleon demands too many eggs. You’ll also find bits from F. Scott Fitzgerald, William Faulkner, P.G. Wodehouse, Mark Twain, and this impish squib from Christopher Moore:

He met his day in the shower, washing his hair with shampoo that was guaranteed to have never been put in a bunny’s eyes and from which ten percent of the profits went to save the whales. He lathered his face with shaving cream free of chlorofluorocarbons, thereby saving the ozone layer. He breakfasted on fertile eggs laid by sexually satisfied chickens that were allowed to range while listening to Brahms, and muffins made with pesticide-free grain, so no eagle-egg shells were weakened by his thoughtless consumption. He scrambled the eggs in margarine free of tropical oils, thus preserving the rain forest, and he added milk from a carton made of recycled paper and shipped from a small family farm. By the time he finished his second cup of coffee, which would presumably help to educate the children of a poor peasant farmer named Juan Valdez, Sam was on the verge of congratulating himself for single-handedly saving the planet just by getting up in the morning.

There’s plenty more. It’s possible I didn’t comb Persky’s archive closely enough, but I did notice the absence of Walter Wangerin Jr.’s National Book Award-winner, The Book of the Dun Cow, in which the rooster Chauntecleer earnestly but naively rules over his barnyard. When forced to confront utter darkness in the form of the Cockatrice, Chauntecleer must endure suffering that ultimately transforms him.

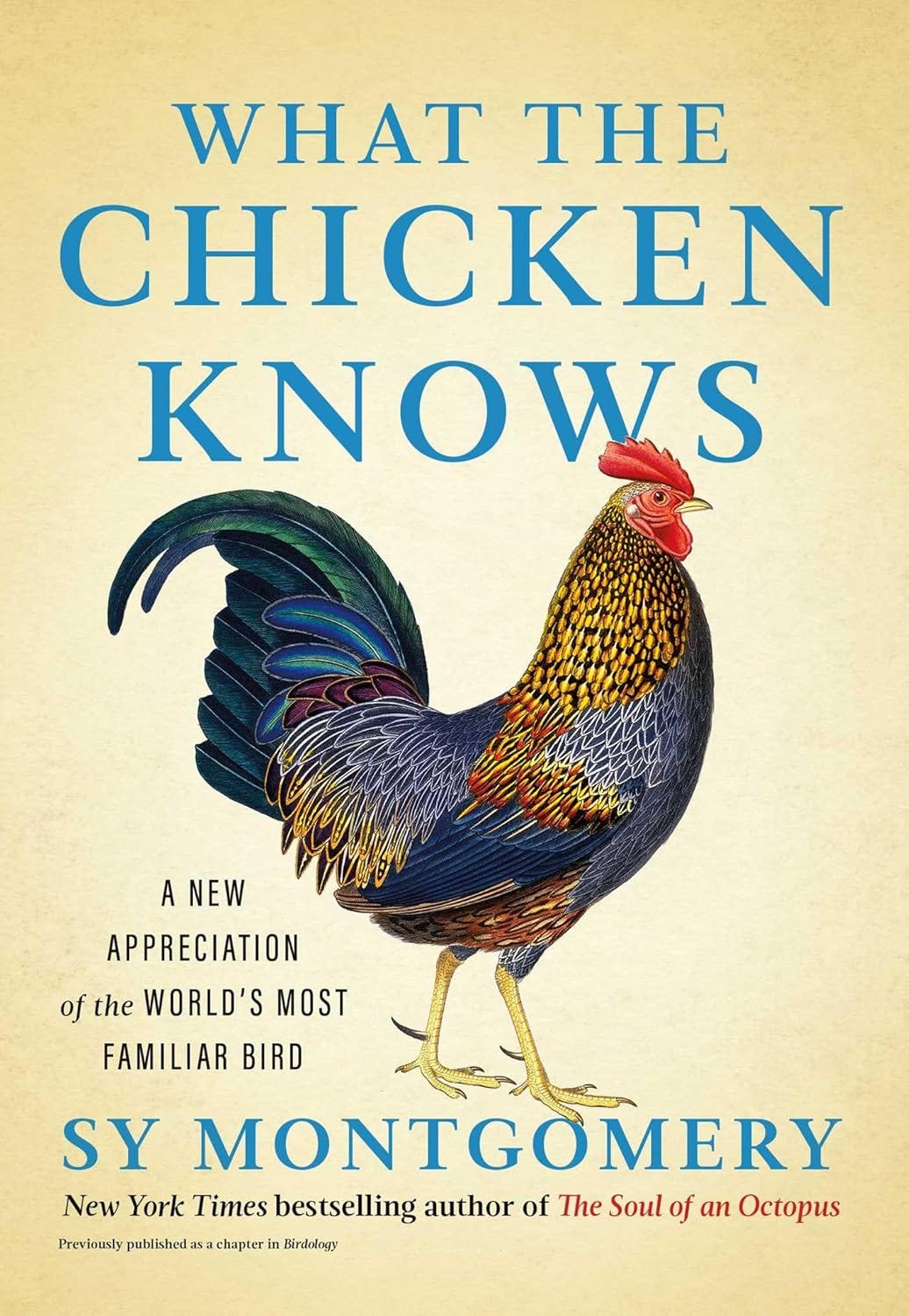

This fascination with chickens is easy enough to explain. On almost every part of the globe, they are part of our daily lives. “Still,” as Sy Montgomery says, “chickens are rarely celebrated in our culture and rarely given the respect they deserve.” She sets out to remedy that fault in her delightful essay What the Chicken Knows.

For the Birds

My dear wife wants chickens. I don’t. My parents kept chickens, and all I remember about them is how filthy they were. My hesitations aside, people have and love their birds. Montgomery knows why; they’re fascinating—a fact I now readily concede, having read her book.

“An average chicken,” Montgomery reports, “can recognize and remember more than one hundred other chickens.” That’s a number two-thirds the size of Dunbar’s number for humans, 150, suggesting that chicken society is more complex than we’d likely assume.

The pecking order is about more than hierarchy, for instance. Dominant hens can serve as peacekeepers in their flocks. Chickens use unique vocalizations to communicate a range of ideas, including the desirability of food, even the identity of their owners. Owners insist on their birds’ individuality. “Jan is nothing like Goldie,” one tells Montgomery.

Still, there’s a hard edge lest we be lulled into soft and easy anthropomorphizing. “There is a lack of pity in all birds,” says one owner. A hen in molt may, for example, be forcibly excluded from the coop. And that lack of pity shows up in another area Montgomery mentions but doesn’t dwell long upon—the violence of roosters.

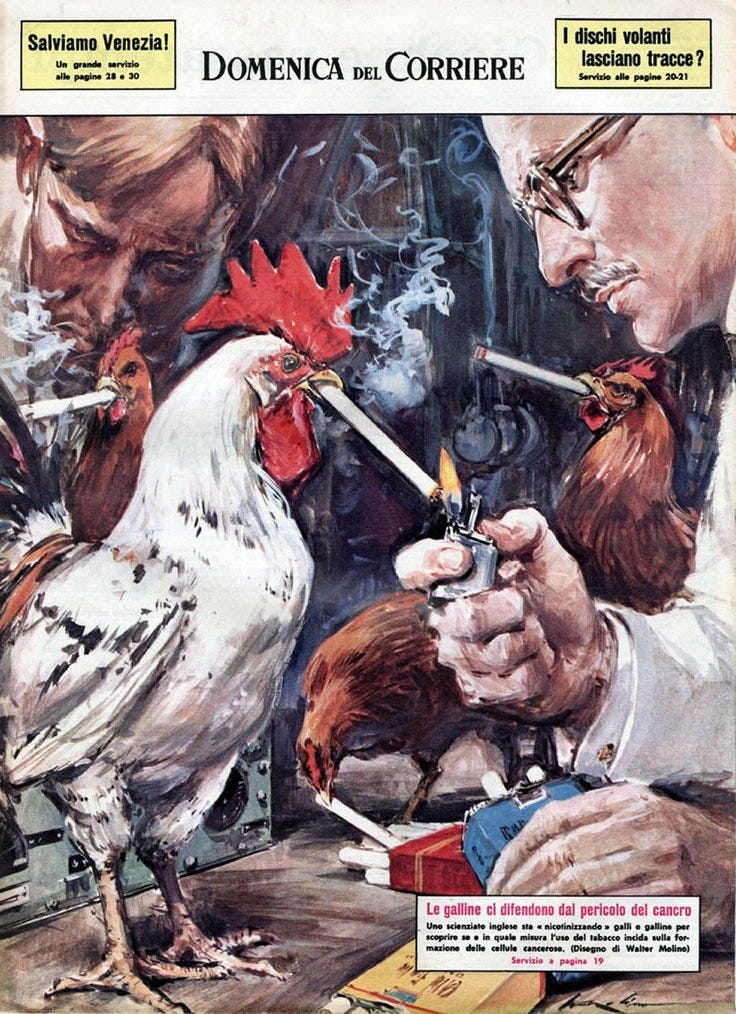

Like Chauntecleer, roosters protect their hens, and they can be bloodthirsty rivals when pitted against each other. All through human history, people have transformed that protective tendency into vicious entertainment in the form of cockfighting. Gabriel García Márquez uses cockfighting as a narrative and thematic device in One Hundred Years of Solitude; a cockfight triggers the novel’s action and drives the development of its masculine characters.

José Rizal fills an entire chapter of his classic novel of the Philippines, Noli Me Tangere, with a cockfight. “In general, to sanctify Sunday afternoon, people in the Philippines go to the cockpit,” he says. “The poor man goes there to risk what he has, wishing to get money without working. The rich man goes as a distraction, using the money left over from his feasting and the purchase of masses.”

Rizal offers this description of a battle between a white cock and red cock, both fitted with blades:

Danger invigorates them, and they come toward one another, decisively, but when one step remains between them, they stop. With a fixed regard they lower their heads and again peck at their feathers. At that instant . . . with a natural bravura they impetuously throw themselves at each other. Their beaks smash into one another their breasts against one another, steel against steel and wing against wing. The parry the blows masterfully and only a few feathers are lost. They take each other’s measure again. Suddenly the white one flies up, and rises up, thrusting out the deadly blade, but the red one bends his legs, lowers his head, and the white one has only caught air. When he comes back to the earth, trying to avoid an injury to his back, he turns quickly to face front. The red one attacks with fury, but defends himself calmly. No wonder he was the crowd’s darling. Everyone follows the movement of the combat, anxious and shaky, emitting an involuntary shout from time to time. The ground starts to get covered in red and white feathers, tinged with blood. . . . Blood wets the earth, the blows come more frequently, but still there is no clear victor. Finally, with a supreme effort, the white one throws himself into a final blow, thrusts his blade into the red one’s wing, cleaving in between the bones. But the white one’s breast has been injured; both have lost a great deal of blood, taken to their limit, exhausted, yoked to one another, they remain immobile, until the white one falls, blood spurting from his beak. He staggers, in the throes of death. The red one, his wing caught, holds to his side. Gradually his legs crumple, and he slowly closes his eyes.

Then the judge, in accordance with what the government prescribes, declares the red one the victor.

Given cockfighting’s deep cultural roots and appearance in literary fiction, it shouldn’t surprise us to see an entire novel dedicated to the sport. Shouldn’t, but did for me.

Subscribe for More

If you enjoy what I’m doing here, subscribe for more joy! I publish a literary essay and a review every week—and it’s always free.

The Pits

I don’t remember where I first saw it—on some list of offbeat, oddball, underloved titles. But it stood out like a sore something. A native Californian, I’ve long been drawn to the grotesque and gothic of Southern fiction. Charles Willeford’s 1972 novel Cockfighter possessed all the basics: lost inheritance, family drama, alienation, doomed love, revenge.

Best known for his Hoke Moseley detective novels set in Miami, Willeford painted with all same familiar colors but chose an entirely different canvas: the cockfighting pits of Florida and Georgia.

The narrator? Frank Mansfield, thirty-something professional cockfighter. The setup?Frank starts the story with just ten bucks. His last bird dies in a fight. He needs to regroup for the next season of fights or he’s done for. The story arc? Frank needs to raise enough cash to buy more roosters, reenter the circuit, and win big at the season’s invite-only final tournament in Milledgeville, Georgia. (Yes, the very same Milledgeville Flannery O’Connor called home.) If he does, Frank stands a decent chance of being named Cockfighter of the Year, the only distinction he really cares about.

Complicating the story? The fact that cockfighting is technically illegal is the least of Frank’s worries. More problematic are such obstacles as getting the required scratch to buy more birds; navigating expectations with a fiancée dangling off the end of an eight-year commitment; collecting debts from people just as broke as he is; rousting his underemployed brother off the family farm; and doing it all having taken a vow of silence.

That’s right: Frank hasn’t uttered a word since he let his big mouth sink his prospects a few years before. He refuses to speak again until he’s redeemed himself. While he narrates the story for the reader in blunt but vivid prose, he only communicates to those around him through body language, small gestures, and the occasional scribbled note.

As Frank rebuilds his flock, Willeford conveys all the intricacies of the ancient sport: the bird breeds, their personalities, their diets, their training, their conditioning, the brutal methods used to decide if a bird is “game,” the language and techniques of the fights, the etiquette of the pits, the size and positioning of blades attached to a bird’s sawed-off spurs, how to get the jump on an opponent, and blow-for-blow descriptions of the fights themselves. Whereas Rizal gives readers a taste for the scene, Willeford serves the entire distasteful but fascinating meal.

Willeford also somehow manages to make Frank sympathetic to a surprising degree. Frank is, as his name might too easily suggest, honest. And his matter-of-fact way renders him relatable, despite living in a world to which we most of us have no access—hopefully (ahem).

The humanizing happens by degrees. At first, we feel sorry for the guy with the worst luck in the world. As he begins rebuilding, the sympathy comes from the relationships Willeford depicts, especially with an old-timer retiring from the sport to save his failing heart and a former Madison Avenue ad man who chucks his career to raise gamecocks on a neighboring farm.

Willeford cares little about character development in the usual sense. Frank’s moral arc is as flat as the Florida landscape. He doesn’t grow as person, experience any epiphanies, or repent of anything. He does defy the odds and become shrewder. But the real test of his character comes down to whether he’ll break that vow of silence while trying to redeem his place in the sport he loves. Without that vow, Frank’s life would dissolve.

“It is a funny thing,” he says.

A man can make a promise to his God, break it five minutes later and never think anything about it. With an idle shrug of his shoulders, a man can also break solemn promises to his mother, wife, or sweetheart, and, except for a slight, momentary twinge of conscience, he still won’t be bothered very much. But if a man ever breaks a promise he has made to himself he disintegrates. His entire personality and character crumble into tiny pieces, and he is never the same man again.

I don’t buy it, not for a minute; people break promises to themselves all the time. But Frank believes it wholeheartedly, and the entire novel depends on his commitment to himself. The vow forms the closest thing to a moral center in Frank’s world.

As you might guess, Willeford offers no ethical guidance through this strange, even revolting world. He simply lets the story work by its own logic, unconcerned about squeamish readers, reasonable as their recoil might be. You’ll need to bring your own moral GPS.

And while roosters may be naturally feisty, Sy Montgomery offers another method of dealing with them than letting them fight to the death. She suggests picking them up and cuddling them under the arm. Turns out they turn fairly docile when snuggled.

What overlooked features of daily life do novels surface for you? Comment below. And don’t forget to hit the ❤️ icon and share this review. Thanks!

Where is the Christopher Moore excerpt from? It's hilarious!

Love this post and have some reading to do!

Glad the Book of Dun Cow was mentioned… the “children’s book” that really isn’t for kids… but is great for 13 and up! The river rising still troubles my dreams…