Worth a Thousand Words: Books with Pictures

Ancient Images and Modern Trends: How Images Illumine the Words We Read

I bet we all have vague to vivid memories of hearing books with pictures are for kids. And true enough, it’s tough finding an unillustrated children’s book. But historically speaking, books of all kinds have featured images—still do. In fact, says illustrator Chris Russell, “Book illustration has existed in some form since the advent of the written word.”

Diagrams and illustrations are often necessary in scientific and mathematical literature to fully communicate the concepts under discussion. That’s always been true. Aristotle’s treatises on biology, for instance, contained images of the animals he described and even dissected. And Euclid’s Elements often featured diagrams to serve comprehension. See below.

Working by Hand

Throughout the classical and medieval periods illustrations and diagrams were individually hand drawn and/or painted along with the text. Such illustrations could prove very useful. Curious about hunting rabbits? Here’s an image from the Queen Mary Psalter featuring a pair of women using a ferret to flush a hare from its hole. Handy if you need to catch your dinner—and with inflation these days, you never know.

Luxuriously rich and hypersaturated colors could be achieved using a mix of substances, some quite rare and expensive, including gold leaf and ultramarine made from lapis lazuli. By studying the remains of a German nun from the eleventh or twelfth century, scholars determined she likely worked illuminating manuscripts. How? She had particles of lapis lazuli in her teeth, probably from licking the end of her paintbrush.

Above find a bright and florid miniature of St. Peter, encircled within the loop of a “P” at the start of his name, “Petrus.” If you want to see more beautiful medieval illuminations, see this article at the Guardian, “Everything Is Illuminated: The Wonder of Medieval Manuscripts—in Pictures.”

The Arrival of Print

The manual work of hand-copying was partly automated in the fifteenth century by printing with moveable type. And images? Printers hired engravers to carve scenes using wood and later other media, such as copperplate. Once inked and pressed, these carvings yielded black-and-white images that illuminators could then color if desired.

I’ve included below an unadorned print, engraved by Jan Collaert I in about 1600, one in a series called Nova Reperta or New Inventions of Modern Times. This particular image shows the inner workings of a print shop. The man cranking the massive screw operates the press itself—pressing the inked type onto the page. Below that, you’ll find a hand-colored woodcut of the city of Nuremberg produced in 1493.

The American revolutionary Paul Revere, best known for his famous ride, was also an illustrator. You can find his work here. And if you want to learn more about woodcut illustrations, the website I Love Typography has a helpful article worth reading. And the University of Adelaide has a great online exhibit of book illustration that introduces classic techniques and the technologies employed, everything from early woodcuts to later lithographs.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free, and I’ll send you fifteen of my favorite quotes about books and reading.

Shifting Tastes

In his brief history of book illustration, Chris Russell mostly focuses on the modern. Charles Dickens, for instance, worked closely with illustrators to ensure they crafted images that matched his characters and plot lines. He partnered with one illustrator in particular, Hablot K. Brown, who published under the pseudonym “Phiz.”

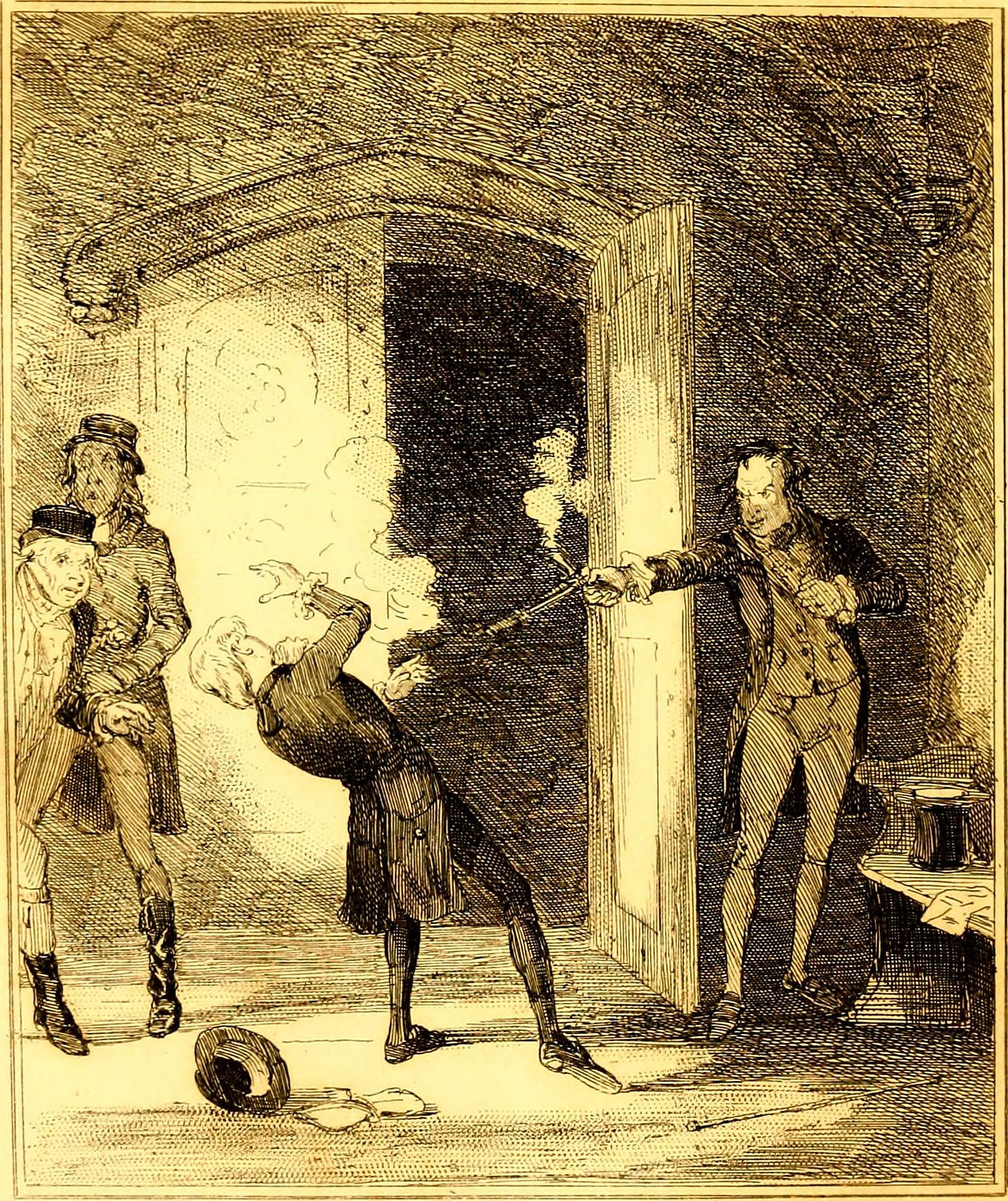

Brown also worked on many projects beyond Dickens. Here’s a Phiz illustration from The Chronicles of Crime, billed as “a series of memoirs and anecdotes of notorious characters who have outraged the laws of Great Britain. . . .”

After centuries of readers’ ready appetite for illustration, tastes changed in the early 20th century. Says Russell,

The practice of publishing visual representations alongside text in adult literature saw a major decline, and book illustration became increasingly associated with children’s literature and “low-brow” or popular writing (such as Classics Illustrated).

Artists were still working and still developing new and more interesting ways to convey stories with images, but they had to find different outlets. Some, as Russell points out, shifted to children’s literature. Hence the bugbear that “books with pictures” are kids’ books.

Kid lit does have a rich history of illustration (more on that here), but it’s definitely not the whole story (more on that here). And, modifying what I said at the top of the post, there’s at least one kid’s book proudly sans pictures.

Many illustrators have been able to exercise their skills in the world of graphic novels where conventions are loose and open to reimagination. While most graphic novels are fictional, for instance, there’s nothing stopping an artist from doing history or biography. Cartoonist Peter Bagge has done exactly that, publishing biographies of Margaret Sanger and Zora Neale Hurston, the latter of which was enthusiastically reviewed by NPR.

What about the use of photos, diagrams, and other illustrative material? Yes, of course, and obviously. In the realm of nonfiction, especially history, access to archival material has never been greater. Prioritizing greater inclusion of images, documents, and the like gives readers a closer feel for distant times and places. While I personally prefer fiction sans images—I usually prefer to conjure those on my own—I appreciate illustration in nonfiction.

What’s Next

As for the future of graphic design and more imaginative illustration, back to Russell:

The future of book illustration is perhaps more open to interpretation and experimentation than it has ever been, with plenty of opportunity for innovation from publishers, particularly when we recognize that writer-artist collaboration is not necessarily bound to traditional format.

It’ll be fun to see what publishers, authors, and illustrators imagine next for their collaborations. I’d love to see more experimentation. Then again, one can also imagine a dystopian future. China’s government recently punished twenty-seven publishing employees, including editors and illustrators, for “tragically ugly” illustrations in math textbooks.

Some were fired and given demerits, which ding one’s standing in the Communist Party; others were ominously “dealt with accordingly.” Along with the penalties, Party officials said they would review all textbooks in circulation “to ensure that the textbooks adhere to the correct political direction and value orientation.”

Given how eager people are to censor whatever displeases them these days, this seems like a grim possibility here as well. Imagine how cramped and colorless the world would be if every image had to conform to a “correct political direction and value orientation,” whether right or left.

No thanks. Such criteria would drain the life from illustrators and the luster from their illustrations.

Thank you for reading! Please share Miller’s Book Review 📚 with a friend.

If you’re not a subscriber, take a moment and sign up. It’s free, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks, again!

I feel like Tenniel's illustrations for Alice in Wonderland must be mentioned. They created Alice as we know her today - and even Disney borrowed from Tenniel in their original animated film. I once read that Tenniel suffered from migraines with auras and that he drew many of the Alice illustrations the way he saw things during an episode. I just read Stephen King's Fairy Tale and the start of each chapter has a wonderful illustration of the characters on their adventures.

Ohhhh this is wonderful (and thanks for the links)! I've done a few drawings and I'm working on illustrating a poetry book right now. Illustration is difficult on two levels, one just the draughtsmanship skills no matter what medium one works in, but the harder is the creative/imagination side of it. To read a text and then come up with an image that captures its spirit, literal and metaphorical senses, and illuminates and frees the text rather than defines it is really difficult. I spend more time thinking about what the image "is" than I do drawing it, but even then, like writing, an image can take on a life of its own and demand its own life from the illustrator. Great post!