Bookish Diversions: What’s Bono Reading?

Bestseller Confusion, Brains on Books, Cheap Grace, Kurt Vonnegut Turns 100, More

¶ What Bono’s reading. U2 frontman and activist Bono is out promoting his memoir, Surrender. While he’s busy pushing his own book, the New York Times asked him about others: what’s on his nightstand, and so on. Bono reads pretty broadly; he mentions all sorts of poetry, fiction, and nonfiction. Not that he reads everything. “I avoid the self-help genre,” he admits, “though to learn why I’d probably have to read more of them.” I swept through the interview and pulled out a few examples.

On his nightstand: Anne Enright’s novel, The Pleasure of Eliza Lynch and Eugene Peterson’s paraphrase of the Bible, The Message (“Some days I read it, other days it reads me”).

Curiosity-slaking nonfiction: J. Storrs Hall’s Where Is My Flying Car? (“A recent find on how some unstoppable ideas get stopped”).

Favorite book few others know of: Martin Wroe’s collection of poems and prayers, Julian of Norwich’s Teabag (“I’m dipping into it every few days”).

Book he often gives as a gifts: Seamus Heaney’s final collection of poems, Human Chain.

Favorite literary villain: The arch tempter Screwtape from C.S. Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters.

Great books recently read: Colum McCann’s novel, Apeirogon, and Kevin Barry’s short-story collection, Dark Lies the Island, among others.

Classics recently read: Chaim Potok’s My Name Is Asher Lev.

Classics left unread to his embarrassment: Tolstoy’s War and Peace.

Also: News to me but Bono has glaucoma, hence his tinted glasses. As a result he often reads on tablet and listens to audiobooks.

¶ What counts as a bestseller? Bestseller lists “shape the public’s perception of what it is reading and what it should consider reading next,” says Jordan Pruett, but what most folks don’t know is that those lists are somewhat arbitrary.

In 1983, William Blatty—author of The Exorcist—sued the New York Times. His lawsuit alleged that the Times had incorrectly excluded his latest novel, Legion (a sequel to The Exorcist), from its bestseller list—the coveted ranking that purports to show the books that have sold the most copies that week in the United States. According to Blatty’s lawyers, Legion had sold enough copies to warrant a spot on the list, so its absence was due to negligence or fraud, for which Blatty was entitled to compensation. The Times countered with what might sound like a surprising admission: the bestseller list is not mathematically objective; it is editorial content, which is protected by the First Amendment. The court ruled in favor of the New York Times.

Bestseller lists “are not a neutral window into what the public is really reading. Rather,” says Pruett, “they reflect editorial decisions about how and what to count.” Pruett covers ninety years of the New York Times’s famous list to explore the intersection of those editorial decisions and changing public taste.

¶ This is your brain on books. Bestseller lists affect culture; so do books themselves—as evidenced in our very brains. Let’s say you read a book this weekend. Safe bet, no? What kind of effect did it have on you? According to Gregory Berns, professor of psychology at Emory University, fMRI scans show that lasting effects might show up in you “sensorimotor strip . . . where tactile impulses enter the cortex and motor impulses leave.” Here’s his theory as to why: When we read an exciting narrative, we can enter the story, creating memories that fuse our self-concept with the actions of the characters. The sensorimotor strip retains those impressions and helps fold the described actions and what they meant into our identities—identities from which we act in the real world after reading.

¶ More than words. When someone fails or disappoints, it’s usually not enough to come clean and express regret. At some level we know that’s too easy, and the stories we tell in literature and history reveal we’re unsatisfied by cheap grace. James Broughel, who runs the Literary Economist here on Substack, tackles this dynamic by comparing the idea of repentance with what economists call “revealed preference.” “When repenting, as with revealed preference, actions speak louder than words,” he says.

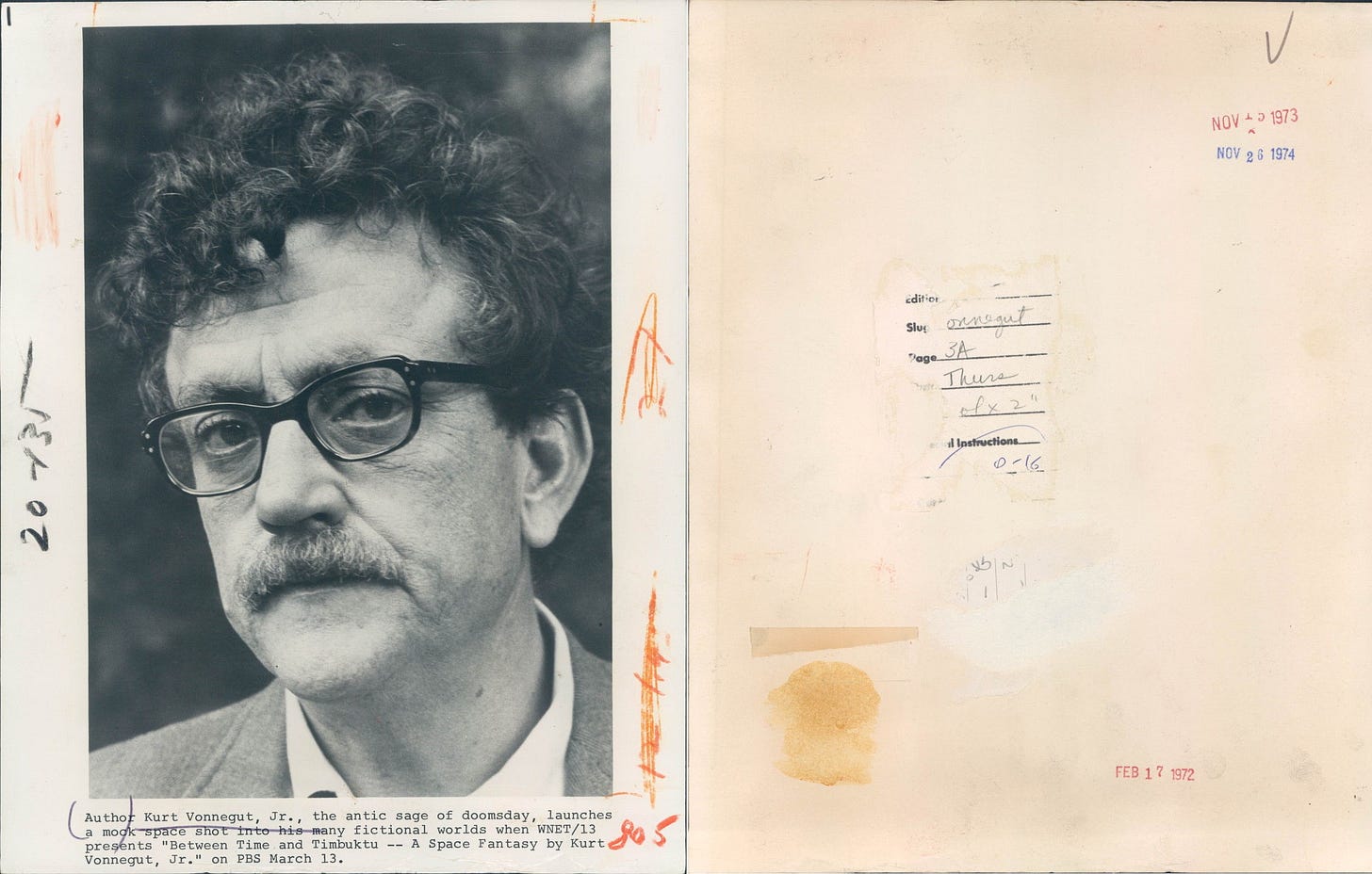

¶ Guess who’s turning 100? He’s famous for disliking semicolons, among more notable achievements. While Kurt Vonnegut’s semicolon aversion has been exaggerated, his legacy has not. (He died in 2007.) When you grow up in a baffling world, mayhem and death manifesting at random and sometimes at scale, you might as well crack jokes. Writing novels of “empty heroics, low comedy and pointless death” was how Vonnegut processed his mom’s suicide (committed the day before Mother’s Day, 1944), the horrors he witnessed in World War II (he lived through Dresden), and the Cold War’s existential threat of nuclear annihilation (three words: Cuban Missile Crisis). Gallows have a way of inspiring levity; somehow, facing death also made Vonnegut lovable. When someone drops pretense and draws the crazy world as it is—or as close as he can manage—he’s bound to earn some loyalty from people who appreciate the honesty.

¶ It’s Greek to me. Actually, no. “Why do billions speak languages with large Latin heritage while less than 14 million speak languages derived from Ancient Greek?” To answer that question, economist Rafael R. Guthmann unspools some fascinating history.

¶ Parting thought.

How many times have I wandered through the stacks of a library, beset by exhaustion and daydreams, only to pull out a random book and find that this text has been waiting to find me? Libraries, a kind of zoo for texts, can feel magnetized this way. All of those words, pressed tightly together, hoping to be opened, to be witnessed.

—Peter Rock, “Why Do Found Texts Fascinate Us So Much?”

Thank you for reading! Please share Miller’s Book Review 📚 with a friend.

If you’re not a subscriber, take a moment and sign up. It’s free, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks, again!