Bookish Diversions: Thomas Jefferson, Bookworm

Jefferson’s Complex Character, His Bookishness, His Writing, Sources of Inspiration, More

¶ Divided president.

’s Thomas Jefferson: A Biography of Spirit and Flesh has garnered high praise ever since its publication in 2022. World magazine named it their Book of the Year.1 I endorse! I reviewed it when it came out, and it was one of my favorites that year.What makes his treatment unique? Kidd foregrounds the complexities of Jefferson’s character. Here’s how my review summarized those complexities:

Committed to belief in God, Jefferson held to a deity roughly as idiosyncratic as himself. An advocate for republican virtues, Jefferson lived embarrassingly deep in debt. A champion for individual liberty, Jefferson never dealt justly with the people he enslaved.

Nonetheless, Jefferson’s influence forms a deep undercurrent in American life.

In many ways Jefferson’s double-mindedness foreshadows our own era’s difficulty with racial justice. And the same might be said for our ongoing religious conflicts and refusal to live within our means. Thomas Jefferson provokes fascination to the present day because, for better and worse, we are Thomas Jefferson.

If you want to understand America’s third president—warts and all—the best entry point I know is Kidd’s Jefferson.

¶ Jefferson, bookworm. Jefferson was among the most bookish of the founders. Kidd spends a fair amount of time in his biography tracking Jefferson’s book purchases. Library building was, in fact, a major reason for Jefferson’s indebtedness, and selling his library to Congress was a significant source of debt relief. Not that he learned from the experience: After selling around 6,500 books to Congress, he started building another library and digging another hole.

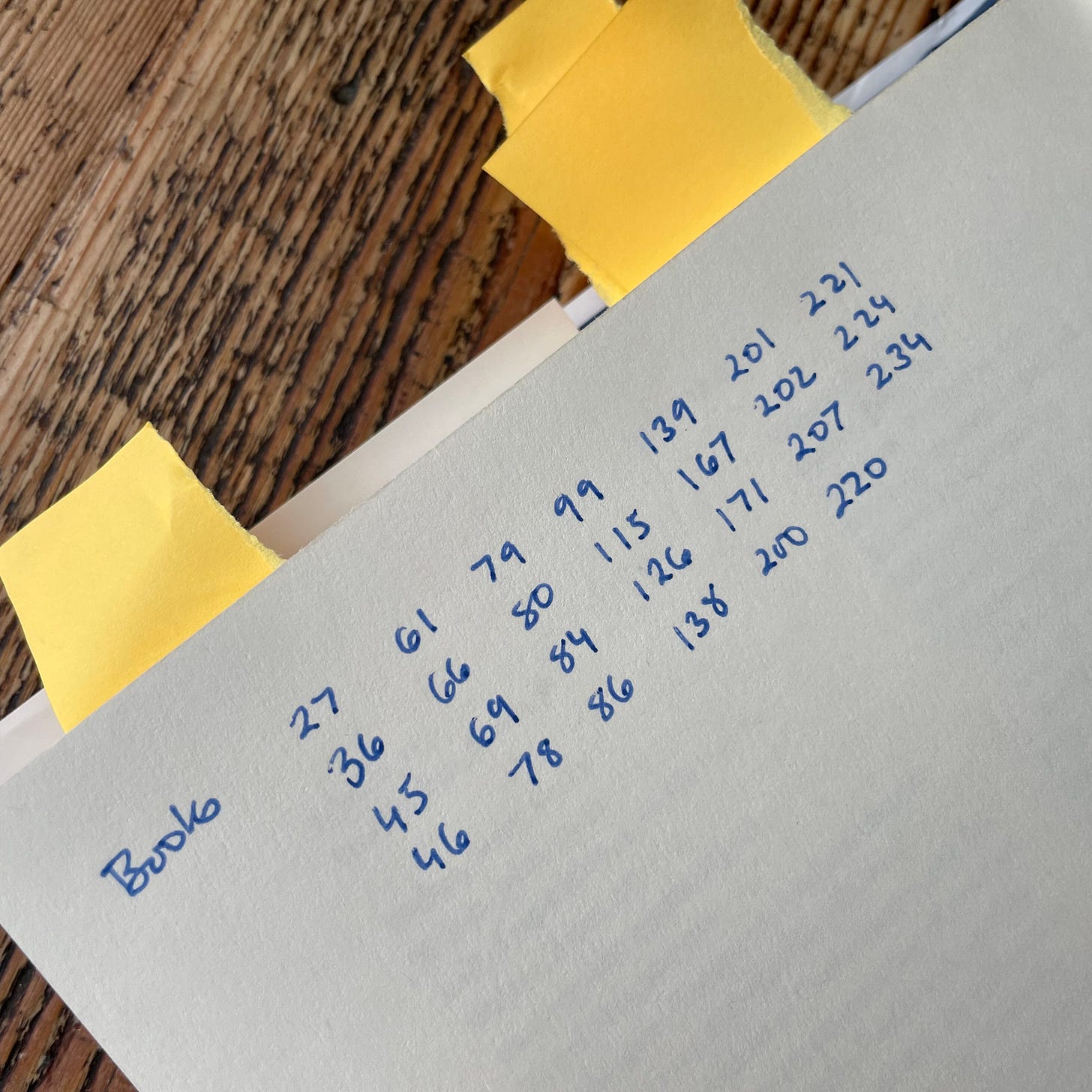

I sometimes keep an index of subjects that interest me in the back of my reading. I did that for references to books in my copy of Kidd’s Jefferson. Every time I ran across a mention, I added it to my index. As you can see, Kidd spends a considerable amount of space on the subject.

In my upcoming book, The Idea Machine (out this November!), I dedicate a chapter to Jefferson and James Madison’s bookishness. Jefferson went on a book-buying spree for Madison while in Paris and shipped two trunks full of books back to his friend. Madison used these very books to help construct and argue for his view of constitutionalism, giving us the form of government we have today.

Jefferson’s library also served him in similar ways. Called by George Washington to a cabinet meeting on negating French treaties, Jefferson prevailed in the debate over Alexander Hamilton because he possessed better command of the legal authorities; he read more—and more deeply—than his nemesis!

¶ Writing history. In its profile on Kidd, World mentions what

would call his “production function”:On a writing day, Kidd aims for a thousand words. He doesn’t write at home and rarely checks his email outside work hours. Despite his seemingly machinelike productivity, he sets boundaries around his work so he can enjoy time with family and church. Part of the secret to his productivity is what he calls his “writing pipeline.” Once he finishes a draft and sends it to his publisher for comments, he immediately begins working on the next project. “I feel adrift when I am not sure what I am supposed to be writing,” he says. At any given time, he might have as many as three unpublished books in various stages of completion.

¶ Jefferson the writer. Most of the founders knew their way around an inkwell, but Jefferson was especially eloquent and loquacious. He wrote only one book—Notes on the State of Virginia—but one edition of his collected works runs to 12 volumes. Others are longer. So, what’s inside all those covers?

Jefferson not only wrote the Declaration of Independence, but he penned many addresses, an autobiography, and 100,000 letters, give or take. A biography by Fred Kaplan, His Masterly Pen, explores Jefferson’s life and impact as a writer.

¶ Classical inspiration. Jefferson, and the rest of the founders, were deeply indebted to Greek, Latin, and other Mediterranean authorities. Classical words and ideas show up in their letters, speeches, books, and other writings. Epicureanism, for instance, winks through Jefferson’s reference to happiness in the Declaration. The historian Thomas Ricks explores those sorts of links and dependencies in his book First Principles.

There was something in the air; classical inspiration found expression throughout American life, well beyond the founders, and persisted for decades. “Vestiges of the founders’ fascination with the classics persisted into the early 19th century among many other Americans,” writes Virginia DeJohn Anderson. “New towns bore the names of ancient cities, public buildings followed Greek and Roman designs and politicians reviled their opponents as latter-day Catilines, likening them to one of the most notorious conspirators against the Roman Republic.”

Art historian Sean Burrus has studied the relationship. “For generations of Americans,” he writes,

the history and literature of Mediterranean antiquity was fertile ground for contemporary comparisons. It was universal enough to be brought into debates about the Constitution and founding principles of democracy, slavery and abolition, and women’s rights and suffrage. It was also of great individual significance for Americans of many different backgrounds—a past they were on intimate terms with, despite the millennia and miles separating the United States from the ancient Mediterranean.

Burrus focuses particularly on how classical inspiration shows up in portraiture and other arts.

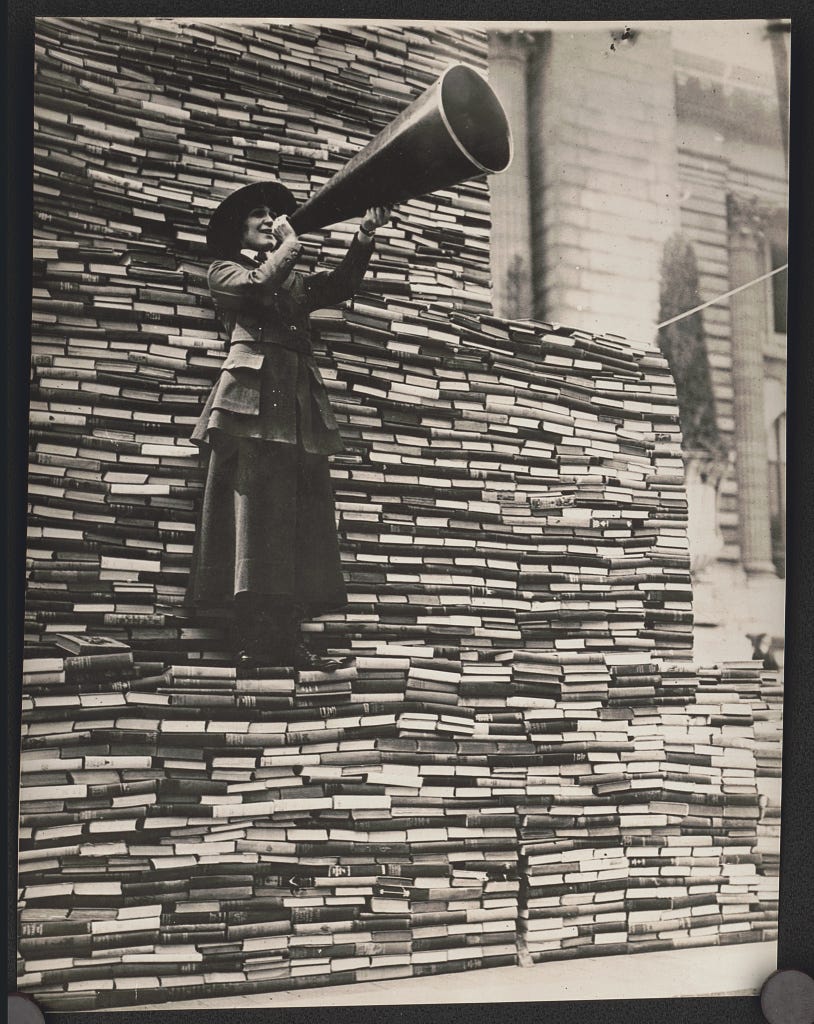

¶ Tools for culture. The pervasiveness of book culture depends on technological innovation. When books were all written by hand, they couldn’t spread far, and readership—along with literacy itself—was naturally low. Printing with moveable type began meeting growing demand and democratizing literature, but penetration was still halted by other hurdles.

In the nineteenth century American book culture saw a boom, thanks to several developments. One of those was steam-powered printing. I tell this story in The Idea Machine:

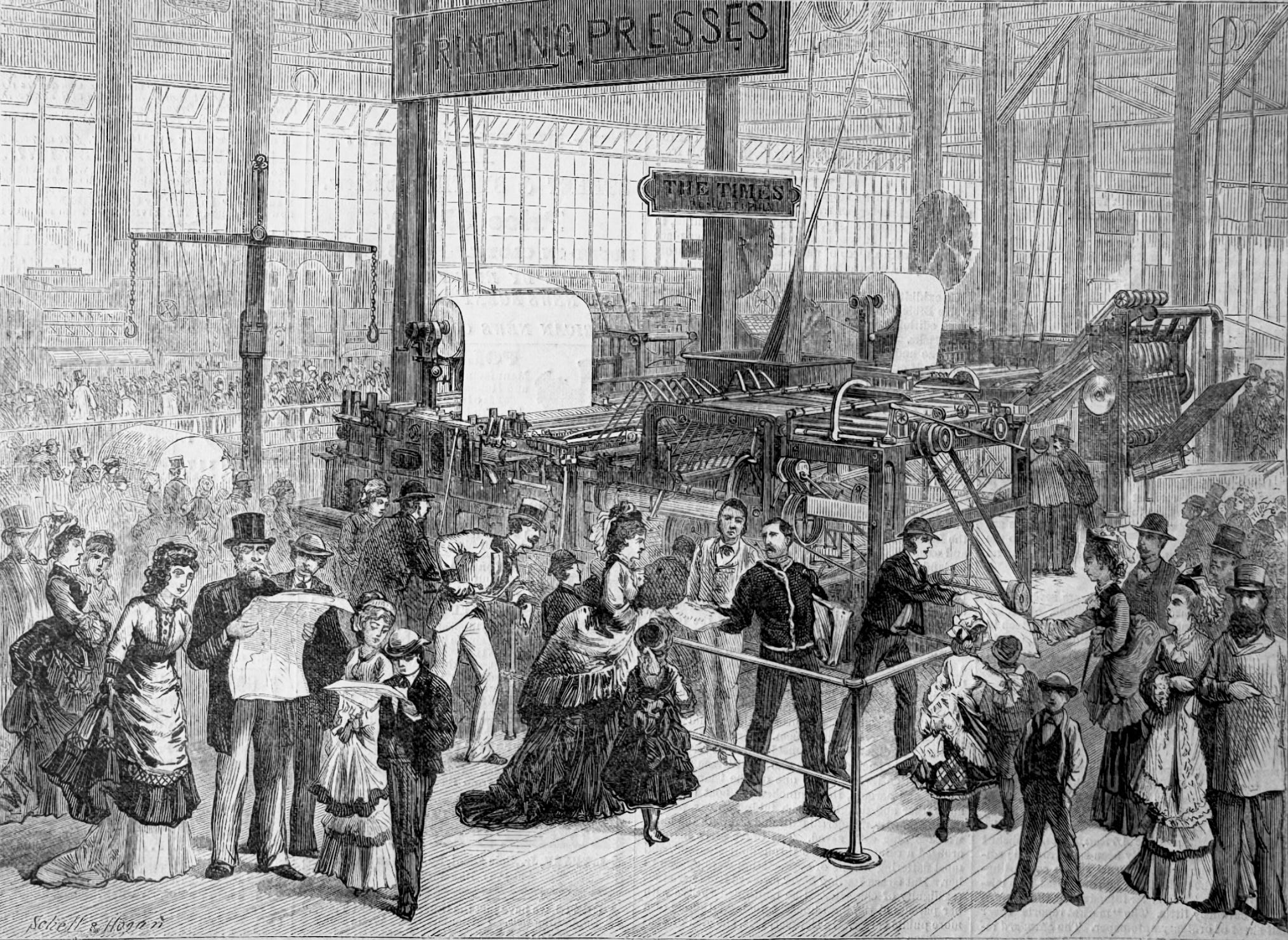

In July 1876 America marked its centennial with an exhibition in Philadelphia. Various technological marvels demonstrated the adolescent nation’s march of progress. Participants could, for instance, see a press owned by Benjamin Franklin capable of printing 150 sheets of paper in an hour. In Franklin’s day, as in Gutenberg’s, each sheet was fed into a flat press and cranked by hand. But a lot can happen in a century.

In the intervening years, innovators powered presses with steam, pressed type on paper with rolling cylinders, and fed paper through the rotors, not sheet by sheet, but in a continuous stream from giant rolls. Inventor Richard Hoe spearheaded many of these improvements; after observing Franklin’s humble press, exhibition participants in Philadelphia could turn and see one of Hoe’s machines in action, spitting out 32,000 complete copies of a newspaper in just sixty minutes.

Steam-powered printing drove market demand but was also responding to it. People wanted more material to read! Denise Gigante captures the spirit of the times in her study, Book Madness,

In New York in the 1840s, books and printed matter were everywhere. Up and down Broadway, boxes of used books cluttered the sidewalks. Newsstands stocked papers, literary journals, and magazines, while street vendors hawked the latest serialized novels by Dickens: “He-e-ere’s the New World—Dick’s new work. Here’s the New World—buy Master Humphrey, sir?”

From storefront windows, new books appealed to pedestrians with siren songs of entertainment and instruction at bargain prices, while literary annuals, gift books, and illustrated editions catered to an expanding American readership. New steam-powered rotary printing technology invented in New York in the mid-1840s revolutionized the print industry, rolling out thousands of pages per hour, while other innovations, such as stereotype printing, enabled a boom in cheap reading matter. By 1851 publisher George Palmer Putnam had begun stocking bookstalls at railway depots with paperback “Railway Classics,” light and entertaining reading for busy persons in transit. Mass-produced paper, machine-made from wood pulp rather than handmade from cotton, also stimulated growing networks of transcontinental and transatlantic correspondence.

¶ Jefferson’s long shadow. I mentioned up top that Jefferson continues to exert influence in our country and beyond. Here’s a striking example from just after World War II, 175 years after Jefferson penned the Declaration. The illustrator Arthur Szyk was a Jew born in Poland in 1894. He worked in Europe through the rise of Hitler, moving to Britain in 1937 and the U.S. in 1940.

Adopting the style of a medieval illumination (as he often did), Szyk created this statement using the memory, words, and visage of Jefferson. “I have sworn upon the altar of God eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man,” said Jefferson. Szyk supplied the rationale in small copy to the left: “The God who gave us life gave us liberty at the same time.”

This was one of Szyk’s very last illustrations. He died the same year he painted it, 1951.

Thomas Jefferson left us a complicated inheritance but one worth engaging; there are still potent remedies in his legacy that could help left and right alike negotiate our perilous present.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below, discuss it in the comments 💬, and share it with a friend!

More remarkable reading is on its way! Don’t miss out. Subscribe for free below.

My own book, Size Matters, a libertarian critique of government growth and market intervention, received a nice notice in World way back when it came out in 2006 (“lively advocacy of small government”).

Thanks for the Jefferson bio recommendation. Pre-ordered your book, but will I read it? I hope so. Is there anything better than a good book?

I visited Monticello this past spring. Had read Willard Sterne Randall's bio of Jefferson in my twenties, but the Monticello slavery tour exposed me to a new facet of Jefferson.

Questions about Jefferson's slave property taken from the Monticello website:

How many people did Thomas Jefferson own?

How could Jefferson write “all men are created equal” and still own human beings?

Did Jefferson free anyone he owned?

https://www.monticello.org/slavery/slavery-faqs/

In addition to the "Behind the Scenes Tour" I recommend the "From Slavery to Freedom Tour" at Monticello.

https://www.monticello.org/visit/tickets-tours/?utm_source=pnav&utm_medium=website

https://www.monticello.org/visit/tickets-tours/from-slavery-to-freedom/

Jefferson Tinder: books and black booty 🌝