Bookish Diversions: The Reason for Libraries

Edge Cases Reveal Deeper Purpose: Mosul, Ukraine, Jerusalem, Baghdad, Syria, and Afghanistan

Libraries represent an attempt to transcend death and dissolution. All our learning disintegrates unless otherwise integrated into a system for storage and retrieval. Orderly shelves of books stand athwart entropy and decay. And while dust is the inevitable end state, a library can buy us decades, sometimes centuries.

But don’t limit this observation to books alone. Learning lives within communities, which means libraries facilitate human connection and cultural longevity. Nothing makes this clearer than observing people’s behavior at the extremes.

Erasing Memory

As aggressors, ISIS and the Russian military have both targeted libraries as a means of erasing cultural memory. In 2014 ISIS torched the central library at Mosul University; a year later they burned the Mosul city library. In all, the terrorist organization destroyed some 100,000 titles in Western Iraq, according to local officials, targeting books of poetry, science, philosophy, and law.

“This destruction marks a new phase in the cultural cleansing perpetrated in regions controlled by armed extremists in Iraq,” said Irina Bokova, director-general of UNESCO. “Burning books is an attack on the culture, knowledge and memory. . . . Such violence is evidence of a fanatical project, targeting both human lives and intellectual creation.”

In its war on Ukraine, Russia intentionally opened a cultural front in the struggle, bombing libraries and archives. “Russians have destroyed more than 300 state and university libraries since the start of the war,” reported Stephen Marche in the December 4 Guardian.

In May, the National Library conducted an online survey on the state of its system. By then, 19 libraries were already completely destroyed, 115 partially destroyed and 124 permanently damaged. The Russians have destroyed libraries in Mariupol, Volnovakha, Chernihiv, Sievierodonetsk, Bucha, Hostomel, Irpin and Borodianka, along with the cities they served. They have destroyed several thousand school libraries at least.

Some of the destruction has been surgical and strategic, representing intentional efforts at erasing specific memories.

In the initial invasion, Russian forces demolished the state archives in Chernihiv, a target containing sensitive NKVD and KGB information about Soviet-era repressions that the Russians wanted erased from the historical record.

Other times the erasures are more general. “They gutted the archival department in Ivankiv for no good reason,” said Marche.

Preserving the Community

The Ukrainians are actively resisting the effort to erase their history. “The destruction of archives can be seen as part of cultural genocide,” said the head of the Ukrainian State Archives, Anatolii Khromov. Local librarians and international Samaritans have been pitching in to secure books and records, protecting collections in armored bookcases and digitizing assets.

But a library is more than a repository. It’s also a network of knowing, feeling, and learning as books pass from hand to hand, mind to mind. For Ukrainians, that’s just as true in wartime as peacetime. In Kharkiv, where Russian bombs have destroyed more than 11,000 buildings, librarians bring books to people still living below ground in bomb shelters. “The library isn’t a building,” said Oksana Bruy, president of the Ukrainian Library Association. “The library is a community.”

These stories underscore the real purpose of libraries: to preserve human memory and community against the acid of time. It’s why aggressors destroy the libraries of their enemies, and why people fight so valiantly to protect their cultural collections.

This dynamic has a long history. According to 2 Maccabees, Judaean governor Nehemiah built a library in Jerusalem, later restored by Judah Maccabee after Antiochus destroyed it in his attempt to wipe out Jewish worship:

The same things are reported in the records and in the memoirs of Nehemiah and also that he founded a library and collected the books about the kings and prophets and the writings of David and letters of kings about votive offerings. In the same way Judas also collected all the books that had been lost on account of the war that had come upon us, and they are in our possession. So if you have need of them, send people to get them for you. (2 Maccabees 2.13–15)

While in Babylonian captivity, Jews turned to their books to provide ideological, historical, and liturgical scaffolding for their community; that reliance enabled them to endure the final loss of their temple at the hands of the Romans in AD 70.

More than a thousand years later when Genghis Khan’s grandson overran Baghdad, the invaders ransacked Muslim libraries. “When the Mongols came here in 1258,” said librarian Abdulsalem Abdulkareem, “they burned the libraries and threw so many books into the River Tigris that the water ran black from the ink.” Only a few books could be rescued, he said, pointing to one famous survivor: a thirteenth-century Quran commentary and theological work, now housed in al-Qadiriyya library in Baghdad.

The origins of the al-Qadiriyya library go back to the eleventh-century founder of a Shia Muslim sect. As a religious shrine, the library has also drawn heat in recent decades. In the 2003 invasion of Iraq the head librarian bricked up the most valuable books in the basement to keep them safe. Ten other local libraries were destroyed, but al-Qadiriyya emerged unscathed. A 2007 car-bombing likewise failed to inflict much damage. And later threats from ISIS—a fundamentalist Sunni organization at odds with the Shia community—also fizzled.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about reading and books.

Rebuilding after Catastrophe

Even when collections are destroyed, books have helped communities rebuild after the disaster. During the Syrian civil war, students in the Damascus suburb of Daraya made news for rescuing books from bombed-out structures and building a new, secret library with the survivors.

“We saw that it was vital to create a new library so that we could continue our education,” said Anas Ahmad, one of the founders. “We put it in the basement to help stop it being destroyed by shells and bombs like so many other buildings here.” Ahmad and his team scoured rubble, sometimes under sniper fire, to salvage volumes. By 2016, they’d amassed 14,000 books.

They kept the location secret to prevent government forces from bombing the site, relying on word of mouth for visitors. Those in the know have put the books to good use. “At first glance the idea of people risking life and limb to collect books for a library seems bizarre,” says Mike Thomson, who covered the story for the BBC.

But Anas says it helps the community in all sorts of ways. Volunteers working at the hospital use the library’s books to advise them on how to treat patients; untrained teachers use them to help them prepare classes; and aspiring dentists raid the shelves for advice on doing fillings and extracting teeth.

Resumed education and medical aid testify to the library’s unique contribution in helping the community reconstitute itself. Thomson has since published a book on Syria’s secret library, as has French-Iranian journalist Delphine Minoui. Here’s an interview PBS did with Thomson:

An inspiring effort in Afghanistan also demonstrates the reconstitutive power of libraries. After securing scholarships to study abroad, Freshta Karim left Afghanistan for Oxford. “War,” she said, “has robbed us of many little pleasures of childhood, including having access to libraries.”

After returning to Kabul, Karim determined to address that wrong. In 2018 she converted a used bus into a mobile library. “I wanted it to be different for our next generation,” she said. “I wanted them to have a space to read, to think, to ask questions and to feel empowered and heard.”

As Olivia Cuthbert reports for Ideas Beyond Borders, “Karim’s organization Charmaghz has [since] grown to include 16 mobile libraries and a staff of 55 people.“ While Afghani children face many challenges, Karim’s mobile libraries provide a place where they can, in her words, “improve their critical thinking skills, ask questions and as a result imagine a world beyond war, then hopefully create it when they grow up.”

That’s the reason for libraries: To safeguard stories and ideas of the past, enabling communities to put them to new and helpful uses in the present and thereby—hopefully—secure a better future.

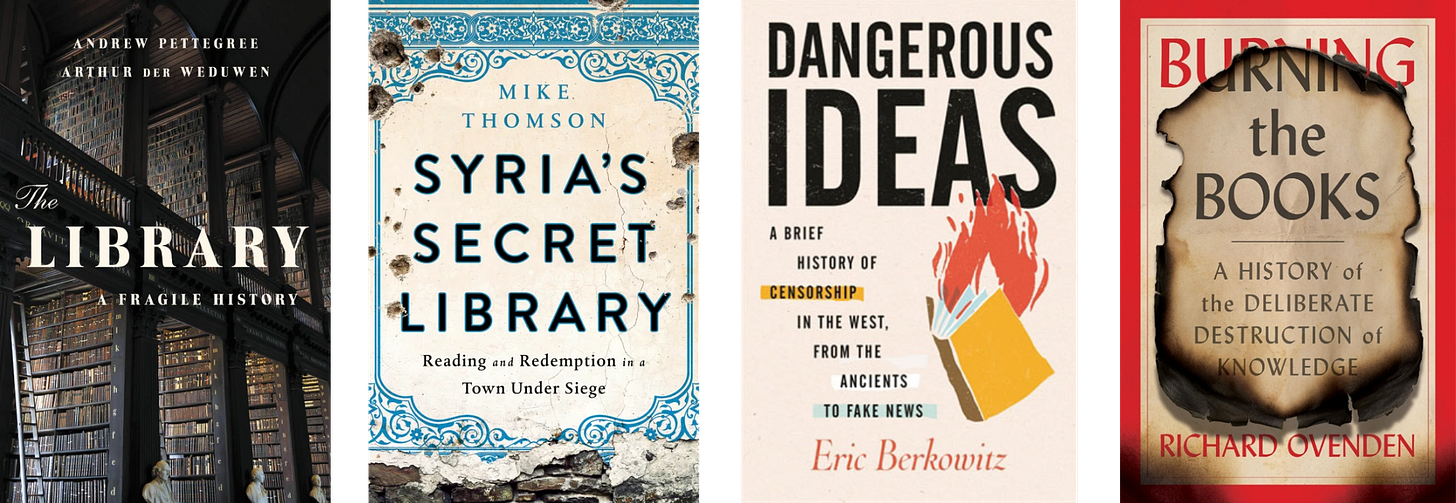

To accompany this reflection on libraries, their intentional destruction, and their community value, I recommend Andrew Pettegree and Arthur der Weduwen’s The Library: A Fragile History, Mike Thomson’s Syria’s Secret Library, Eric Berkowitz’s Dangerous Ideas, and Richard Ovenden’s Burning the Books. I’ve reviewed all but Thomson’s here so far.

Thanks for reading and shaping the community here at Miller’s Book Review 📚! If you enjoyed this review, please share it with a friend.

More remarkable reading is on its way. Don’t miss out. Subscribe for free below.