Bookish Diversions: Shhh! Happens

Younger Americans Love Libraries, Free(ish) for All, Unquiet Librarians, the Library of Mistakes, Tattoos, More

¶ Younger Americans love libraries. Millennials and Gen Zers spend time at their local library more frequently than their elders. “54% of Gen Zers and millennials trekk[ed] to their local library in 2022,” say Portland State University professors Kathi Inman Berens and Rachel Noorda, compared to 45 percent of Gen Xers and 43 percent of boomers.

One reason? While the younger generations spend a lot of time on digital devices engaging social media, they prefer print over digital or audio when it comes to books and, according to Berens and Noorda’s data, average about two print books a month. “Gen Zers and millennials still see libraries as a kind of oasis,” they say, “a place where doomscrolling and information overload can be quieted, if temporarily.“

¶ Changing role of libraries. Almost a quarter of millennial and Gen Z library visitors don’t count themselves as readers, according to Berens and Noorda, a reflection of the widened scope of libraries in recent decades. “Patrons can [also] record podcasts, make music, craft with friends or play video games,” they say. “There are also quiet spaces with free Wi-Fi, perfect for students or people who work remotely.”

All over the world libraries serve as valued third places. “It’s a shared office for students and workers stuck in overcrowded apartments,” writes Nicholas Hune-Brown at The Walrus. “It’s one of the last places you can go to warm up or use the washroom, where you won’t be hustled along by security or forced to buy something.”

¶ Free, but not really. Free seems to be a significant attractor for some. “Haven’t paid for Wi-Fi in three years,” says one woman in a viral TikTok video. “Why? My local library gives out Wi-Fi hotspots, not only that, they give out Roku sticks, so I haven’t paid for HBO Max and Netflix in God knows how long.”

Of course, “There ain’t no such thing as a free lunch,” as Robert Heinlein said in his classic sci-fi novel, The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress. Someone has to pay, and cities are forced to juggle competing financial demands while libraries busy themselves with new offerings to stay relevant. It’s a tricky tension.

¶ Unquiet librarians. Librarians do a lot these days, as Hune-Brown’s article in The Walrus shows. But they’ve always gone a bit above and beyond the standard job description. In the early twentieth century, for instance, literacy in impoverished eastern Kentucky was scant and finding books wasn’t easy. But, during the Great Depression, the federal government sponsored the Pack Horse Library Initiative, assuming improved literacy might ease the region’s poverty.

“The project, as implemented by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), distributed reading material to the people who lived in the craggy, 10,000-square-mile portion of eastern Kentucky,” writes Eliza McGraw in the Smithsonian Magazine. Paid less than the equivalent of $500 a month today, packhorse librarians, mostly women, covered 100 to 120 square mile routes, delivering books to some 50,000 Appalachian families and more than 150 schools.

Then there were the librarians who beat the Nazis. As WWII began, US intelligence gathering was minimal. To remedy the problem, the government established both the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), precursor of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and the Interdepartmental Committee for the Acquisition of Foreign Publications (IDC). The IDC’s role? To fan out through Europe, vacuuming up as much information as possible on the Nazis and the territories they controlled.

Of course, information requires efficient storage and effective retrieval to be useful—and that, as Katie McBride Moench explains, writing for JSTOR Daily—is where librarians came in. “Librarianship and spy craft are well-suited partners,” she says; “both revolve around the collection and dissemination of information. Librarians understand that information possession is not enough. It requires organization and analysis to make such information meaningful.”

Moench details one partnership in Lisbon, Portugal, between Manuel Sanchez of the Library of Congress and OSS agents Ralph Carruthers and Reuben Peiss:

Arriving in Portugal in early 1943, Sanchez spent his first few days shaking the undercover agents trailing him. Once he evaded them, he began buying printed matter he believed would be of value to the Library of Congress. He also cultivated a partnership with the Andrade brothers; they owned a bookstore and were Allied sympathizers. The three men habitually crossed into Franco-controlled Spain to elude suspicion during book-buying expeditions. Meanwhile, Carruthers, an expert on microfilm, photographed thousands of pages of text, and Peiss, a librarian, developed systems of information classification and retrieval for the mass of intel collected. So extensive was their work that staff members worked ’round-the-clock shifts to photograph obtained documents, using micro-cameras to create microfilms that would be shipped on a Pan Am Clipper.

¶ Upgrading the research desk. The microfilm used in spy work found parallel uses in libraries, universities, and other research institutions. I can recall in pre-internet days consulting old newspapers using a microfiche machine at my local library. Of course, all those articles had to be catalogued by someone. In casual conception, we might imagine librarians as custodians of books, and they are, but they’ve always been more than that. Preceding even Callimachus at the Library of Alexandria, librarians served as information technicians and data scientists.

Writing in Aeon, librarian Monica Westin offers a chapter of that pioneering work from the 1970s when librarians working at the Syracuse University School of Library Science conducted the first online searches between networked mainframe computers.

“While the popular history of the internet valorises Silicon Valley coders,” says Westin,

many of the original concepts for search emerged from library scientists focused on the accessibility of documents in time and space. . . . Their advances can be seen everywhere in the current online information landscape—from general approaches to ingesting and indexing full-text documents, to free-text searching and a sophisticated algorithm utilising previous saved searches of others, a foundational building block for contemporary query expansion and autocomplete.

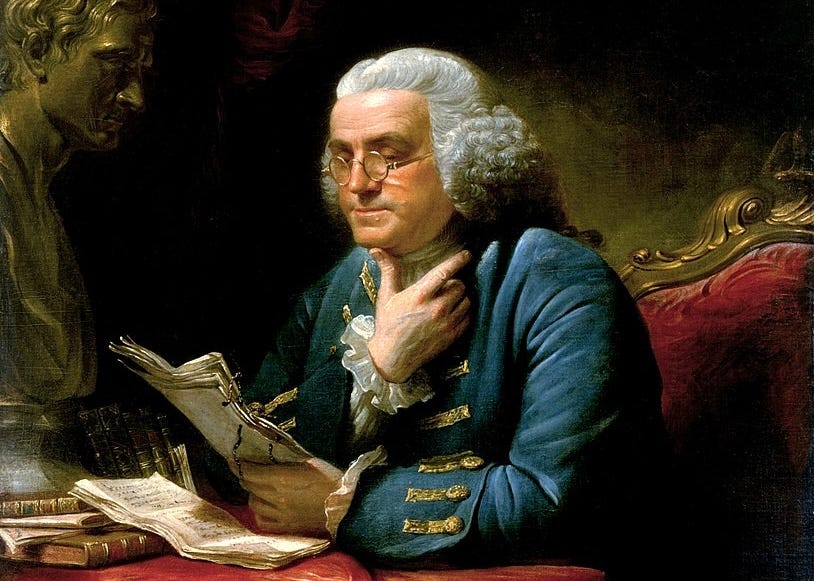

¶ Benjamin Franklin, librarian. The first book I read in my classic memoir goal for 2024 was The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin. Seeing books as essential for personal intellectual development and subsequent societal advances—but also seeing what difficulty books proved to procure—Franklin founded the first subscription library in North America, what became the Library Company of Philadelphia.

Lending books presented challenges. As these 1763 rules for the library attest, common problems included patrons damaging or not returning books, for which fines were levied. I thought of that when I read this contemporary story: “Man returns overdue library book 77 years later.” The more things change. . . .

¶ Library of Mistakes. Franklin’s library company was a private organization. There are still many independent libraries out there, some of which have remarkably narrow areas of focus. Britain’s Independent Libraries Association features an entire network of such organizations and one member looks particularly intriguing, The Library of Mistakes, which focuses on bad economic analysis and financial fraud. “We hold a selection of quirky curiosities and fine collection of books,” says the website, “all related to the ups and downs of financial markets and businesses throughout the years.”

¶ Growing up in the temple of knowledge. As a kid growing up in the 1940s, Ronald Clark lived in his local branch of the New York Public Library. That’s not hyperbole. I don’t mean he frequented the place so often you could say he lived there. Since Clark’s father served as custodian, Clark’s apartment was actually situated within the building itself. Free to roam the shelves whenever he wanted, even late at night, Clark assumed his family was rich. In a way they were. Decades later, Clark narrated this short video, telling his daughter all about it.

¶ If skin were a book. Some librarians take seriously Mike Roe’s injunction in the 77s song, “Tattoo”:

If you say I'm written on your soul

Then write me on your skin

In his Walrus article, Nicholas Hune-Brown mentions the ankle tattoo sported by Calgary Public Library CEO Sarah Meilleur: “the Dewey Decimal number for books about librarians.” And Fairfield Civic Center librarian Mychal Threets, profiled in the San Jose Mercury News, wears a tattoo of Arthur Read’s library card. Arthur is the adolescent aardvark character created by author Marc Brown and, as every parent knows, popularized by a PBS cartoon.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related posts:

Historical fiction I enjoyed regarding the Pack Horse Library: Kim Michele Richardson's The Bookwoman of Troublesom Creek and The Bookwoman's Daughter.

I didn't exactly grow up inside a library. But for a few years in my childhood, my mother worked part-time as an assistant librarian. She was a homemaker and homeschooler, so, when she worked, we came with her. We brought our workbooks, but I spent more time reading from the shelves than doing homework. Since then, libraries have felt like places of refuge. When I lived in the city as a poor student, my recreational outings were usually to go to the central branch of the public library.