Bookish Diversions: Why Read Shakespeare?

First Folio, Universal Appeal, Teaching Shakespeare in School, but Shakespeare Wasn’t Even Shakespeare, Right?

¶ Staying power. Shakespeare’s First Folio, a mammoth collection of his work compiled by friends and fellow players, has turned 400. Seven hundred and fifty copies were originally published in 1623, seven years after the playwright’s death in 1616. Two hundred and thirty five of these are still extant, mostly in institutional hands; the Folger Library, for instance, holds 82. Some private collectors do possess copies, and it’s thanks to the original private collectors that so many copies have survived the centuries. Shakespeare’s work lives in a category beyond beloved; for a certain kind of person, it’s beatific.

The First Folio laid the foundation for Shakespeare’s legacy. “If we didn't have this book,” says Emma Smith of Oxford University, “we wouldn’t care about Shakespeare at all. Half of the plays would have just been lost. We wouldn’t have Julius Caesar. We wouldn’t have The Tempest. We wouldn’t have Macbeth. And we wouldn’t have all the kind of cultural significance that they have got.”

¶ The Pananthropos. Marking the tercentenary of his death in 1916, Oxford University Press published a large commemoration of Shakespeare and his accomplishments: A Book of Homage to Shakespeare, recently reprinted at its 100th anniversary. It featured praise and observation from leading English scholars, as well as commentary by those far afield—French, Italian, Spanish, Finnish, Persian, Chinese, Armenian, and many others.

One of those commentators was the Serb Nikolai Velimirovich, an eventual hierarch of Orthodox Church, Nazi resister in WWII, and today a recognized saint. “I do not know Shakespeare,” he began. “Even I cannot know him. But he knows me; he described me, he painted all the secrets of my soul in such a way that in reading him I am finding myself in him.”

High praise—and echoed by countless readers of the plays who find the Bard somehow touching on every strand of human feeling and experience. One University of Pennsylvania professor, for instance, refers to Shakespeare’s plays as “enduringly human.” Where does this broad yet particular humanity come from? Despite some overt politics, Velimirovich knew.

In his praise, Velimiorovich casts the British colonial system in light more positive than we might support today. He does so to create a polarity between the English and the Germans during World War I. It’s there in his title, referring to Shakespeare as the Pananthropos, Greek for “All-Human.” Velimirovich pits this Pananthropos against Nietzsche’s Übermensch, the conquering “overman” who would transcend and discard all prior, lesser cultural forms.

Against this overman, as Velimirovich sees it, stands Shakespeare—the universal man, who embraces the entirety of humanity. How else to explain his astonishing ability to spin out sentences still read and cherished by people around the world who feel somehow seen and known, mirror-like, in all those lines and phrases?

It’s not that Shakespeare possesses universal appeal, but he makes a universal appeal: We should, he says by his own imperfect example through his plays, identify with and connect to the humanity of all people: their hopes and horrors, their thwarted plans and pain, their happiness and folly.

¶ Shakespeare in school. My dad teaches high-school English and has since before I attained the humble status of embryo. God only knows how many people in the greater Sacramento area can still recall random lines of Romeo and Juliet, thanks to my dad.

Some teachers—and many more students—nowadays bristle at the mention of Shakespeare. There’s active controversy about the ongoing relevance of his plays. Pedagogues fret about their supposed eurocentrism, colonialism, toxic masculinity, heteronormativity, and so . . . yawn . . . on. Most students, on the other hand, just find him impenetrable. For good reason, as John McWhorter argues.

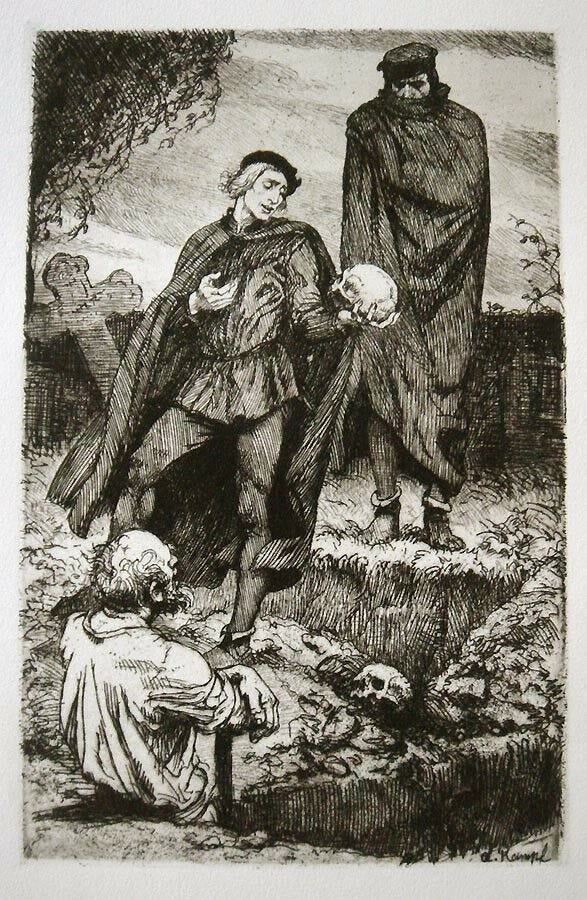

The language can be daunting, but there’s merit in the challenge. “My students were born a few years before the first iPhone-anvil crashed through our attention spans,” says Andrew Simmons, who teaches Hamlet every year to his high-school seniors.

A more merciful teacher might cut a word-drunk dinosaur like Hamlet, but I won’t. Not because I’m a canon-worshiper who thinks the mere presence of Shakespeare suggests rigor. With each passing year, I see my students struggle more and more to decipher Hamlet’s torrents of language, but they are also increasingly comfortable with Hamlet himself. As faith in the inevitably progressive trajectory of their world falters, they inevitably understand and identify with him.

Hamlet has always been a vehicle for our existential vibrations. . . .

Simmons goes onto explain how Hamlet speaks to the the confusion and chaos of our time, crises especially felt by teens with little historical context for societal turmoil and even less control over it. What Hamlet provides is way for a person to orient themselves amid all the angst. In other words, a good teacher of Hamlet can solve for all the problems troubling the pedagogues.

“Disinterested as they might be in royal succession drama,” says Simmons, “students find the play reveals, in Hamlet’s words, their ‘inmost part.’” Like Velimirovich, students can find themselves in Shakespeare.

¶ But what if Shakespeare didn’t write Shakespeare? People have agitated on this question since at least the mid-nineteenth century, most recently Elizabeth Winkler in her book Shakespeare Was a Woman and Other Heresies. Writing for Slate, Isaac Butler takes on Winkler’s book and the broader “Shakespeare Truther community” but does so gingerly, cautiously, gently. Why?

Tear it apart, and your vicious pan becomes yet another piece of evidence that Shakespeare Truthers must be on to something. Treat it calmly and even-handedly while still making clear what its problems are, and you risk legitimizing its claims as worth debating. Refuse the assignment and not only might you disappoint your editor, but you allow the book to have the last word.

The problem is that arguments against Shakespeare’s authorship, however interesting or occasionally persuasive, tend to rely on the same methods favored conspiracy mongers, especially when challenged:

Ask an escalating series of questions about the consensus view, shifting ground whenever you would lose the point being debated. Deploy shaky evidence that requires tendentious interpretation. Claim that evidence that disproves your theory in fact supports it. Needle those in power who refuse to engage with you. Use the contempt with which your position is treated as evidence that you must be on to something. Whenever possible, fall back on saying you’re just asking questions.

Trutherism abuses the liberal public sphere by using the values of liberal discourse—rational hearing of evidence, open-mindedness, fair-minded skepticism about one’s own certainties, etc.—against it. Once the opposition tires of this treatment and refuses to engage in debate any longer, the truther can then declare victory, and paint the opposition as religious fanatics who are closed-minded and scared of facing the truth.

In other words, it’s like arguing with a flat earther.

Meanwhile, the focus has lamentably shifted from the thing to the thing about the thing; instead of enjoying Shakespeare, we are (God help us) fixated on the pedantry and intricacies of Shakespeare scholarship. “Hell is empty,” we might say, following The Tempest, “and all the devils are here”—words we wouldn’t even have without the First Folio.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Victor Hugo, 1859: "Two exiles, father and son, are on a desert island serving a long sentence. In a morning, sitting in front of the house, the young man asks: 'What do you think of this exile?' 'It will be long... ", replied the father. 'And how occupy it?', continues the young son. The old serene man reply: 'I will look the ocean, and you?' It is a long silence before the son's answer: 'I will translate Shakespeare.' Shakespeare: the ocean

Thank you for this wonderful post! There truly is merit in the challenge of engaging with Shakespeare's language, and it may well help save students from the abyss of AI language processing tools. I recently wrote a post that dovetails with your article in relation to the Toronto District School Board's decision to drop Shakespeare from its curriculum. See "Tilling the Ground for chatGPT" https://schooloftheunconformed.substack.com/p/tilling-the-ground-for-chatgpt