Bookish Diversions: How Do You Shelve Your Books?

Chronological Shelving, History of the @ Sign, Why Lorem Ipsum Is Nonsense, Audiobooks, Bob Dylan, More

¶ Shelving books by timeline? My history books are mostly shelved chronologically. As it happens, so are Steve Williams’. Why? “I began to store them in chronological order by event,” he told Library Planet, “a little quirky, I know, but it works for me with my love of history and timelines, and enables me to . . . get an understanding of the passage of time and events.” What’s great about this method is you can slide distant voices alongside modern authors who provide them context. My Augustine, for example, enjoys the company of Peter Brown and Robin Lane Fox; the broader context provides better understanding of the saint’s words and opinions.

¶ The history of the @ symbol goes back much further than email. You can read about it here. Meanwhile, what do you call it? The Romance languages seem to have the closest original term: arroba (Portuguese and Spanish), arrova (Catalan), arobase (French). The word seems to point back to an amphora—a jar—used in Mediterranean shipping and refers to a certain unit of measurement. That’s still present in the “official” English term: “commercial at.” But once you get past the historical roots, the name seems to come down to what people think the symbol resembles. Here’s a roundup of what people around the world call that little a with a tail. I can’t vouch for the accuracy of any of these, but they seem plausible enough:

little lamb’s tail (Welsh)

monkey’s tail (Dutch)

elephant trunk a (Swedish, Danish)

curled a (Norwegian)

mouse’s tail or sleeping cat (Finnish)

clinging monkey (German)

little snail (Italian)

duckling (Greek)

worm (Hungarian)

rolled picked herring (Czech)

rolled a (Romanian)

monkey (Polish, Bulgarian)

little dog (Russian, Armenian)

strudel (Israeli Hebrew)

mouse (Chinese)

snail (Korean)

Pregnant O (Nahuatl)

¶ Rosetta Stone. Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs were deciphered thanks to the Rosetta Stone, which contained the same text in a few languages, including Greek. But what did it say? British Museum features a helpful essay here, and you can read a translation of the stone here. British Museum curator Ilona Regulski explains it in the video below.

¶ Greek to me. No, actually Latin. No, actually nonsense. Have you ever seen the copy that designers use when mocking up websites, ads, or anything else that require words? While working to get the visual elements just right, designers will often drop in filler copy known by its opening words, “lorem ipsum.” You’ve probably seen it before:

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Pretium nibh ipsum consequat nisl vel. Nulla porttitor massa id neque aliquam vestibulum morbi. Dignissim cras tincidunt lobortis feugiat vivamus at augue eget.

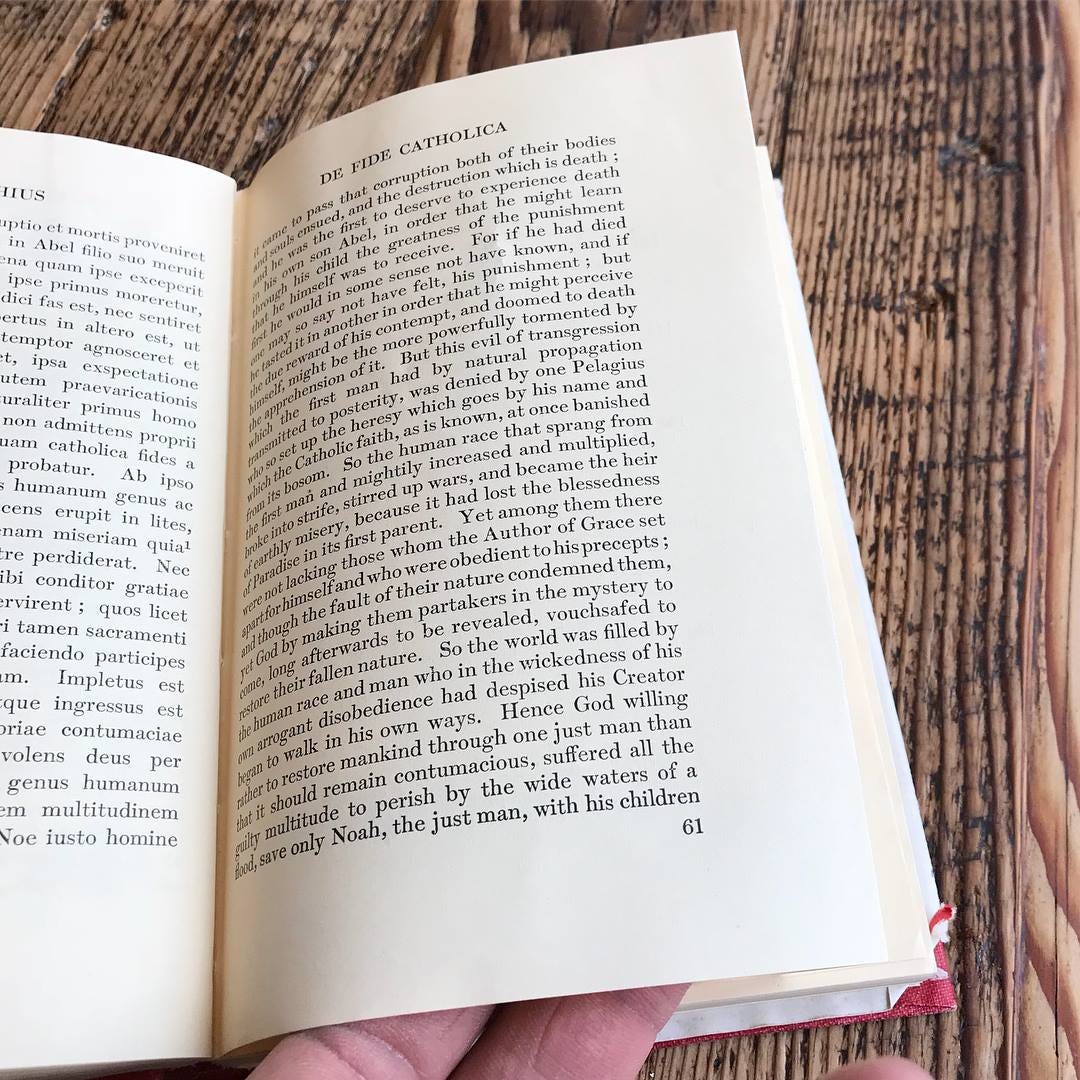

Designers began using it in the late 1960s. But where does it come from? It looks Latin. And it is, sort of. David Butterfield explains its curious origins, cribbed and crinkled from a 1914 Loeb edition of Cicero’s De Finibus. Butterfield shows how much the famed orator has been scrambled into unreadable mush.

“Lorem,” for instance, is part of “dolorem” (sorrow), the opening syllable lopped off because the page in the edition from which the copy was nicked begins midword. The Lorem Ipsum website also provides a history (going back a bit further) with a lorem ipsum generator that spews out untold paragraphs of the stuff.

And speaking of Loebs. . . .

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free, and I’ll send you fifteen of my favorite quotes about books and reading.

¶ Book anomalies. When a book is made, the paper is almost always folded multiple times in the process. Once the book is bound, the folds are cut to reveal each page. But every now and then a page dodges the blade. Notice that this little Loeb jumps from 61 to 64. What happened to 62 and 63? They’re hiding in the fold! This is an old copy of Boethius’ Tractates and Consolation. It’s been well read and annotated in places—but evidently not this section. I’ve had it for years and can’t bring myself to cut the pages open.

As if that weren’t bad enough, this book has additional problems. In modern bookmaking, each bundle of folded pages is called a signature, and each “sig” amounts to a number of pages divisible by eight (typically 8, 16, or 32 pages). One of the signatures in this book was never properly sewn in place and regularly falls out. I also can’t bring myself to replace it.

¶ When we think of apps, we tend to think of digital devices. But if you broaden the definition a bit to include interactive analog tools for accessing and applying important information, then the little volume pictured below qualifies as a “smart book”—especially once you factor it’s erasable note-taking function. Click the box to read the thread.

![A photo of my left hand holding the book. I am a 5'4 woman with small hands, and it fits comfortably in my hand and is roughly the length from my wrist to the tip of my middle finger. What we can see of the book here is the leather upper binding, which has been blind tooled with a centerpiece in the shape of a long lozenge. For information on the technique known as "blind tooling" [I'm conscious of the awkwardness of writing that here], consult this link: https://library.princeton.edu/visual_materials/hb/cases/blindtooling/index.html](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!qI9d!,w_600,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fpbs.substack.com%2Fmedia%2FFTDVRPyXoAAGJVC.jpg)

¶ Being read to. Audiobooks offer several advantages unique to the format, among them being the as-old-as-time experience of having someone tell you a story. Here’s James Parker on the format from this month’s edition of The Atlantic.

Being read to is ancient. I love a podcast—the chitchat, the colloquy—but this is deeper: the reading voice, the singular storytelling voice, thrums in the memory tunnels of the species. When I'm listening to an audiobook, I'm being entertained like a tired ploughman. I’m being lulled, bardically lulled, like a drunken baron at a long feast table, pork grease shining on my chin. I’m being quieted like a child. I’m being spellbound like a face caught in firelight.

When it comes to novels, I actually prefer audiobooks. Sometimes I wait for the audio to start a novel if print and audio aren’t released simultaneously.

¶ Blowin’ in the wind. Speaking of audiobooks, Bob Dylan’s newest, The Philosophy of Modern Song, comes out next month; naturally, there’s an audio version. The publisher has arranged a great cast of readers to cover Dylan’s essays on a range of popular songs. Helen Mirren, Sissy Spacek, John Goodman, Rita Moreno, and others all take turns. Jeff Bridges gets “Pancho and Lefty” and “Your Cheatin’ Heart.” Rene Zellweger takes “On the Road Again” and “Truckin’.” And Steve Buscemi has “Dirty Life and Times” and “Viva Las Vegas.” Here’s the full roster of readers and songs.

And what about the author? Dylan reads but only bits and pieces. “He will read short introductions or interstitial pieces that appear between chapters in the book,” according to Variety, “described by publisher Simon & Schuster as ‘a series of dream-like riffs that, taken together, resemble an epic poem and add to the work’s transcendence.’” I’m in. This is one I’ll be acquiring in physical and audio formats.

¶ In the bard’s own words. The New York Times has an excerpt of The Philosophy of Modern Song. This quote stood out:

Each generation seems to have the arrogance of ignorance, opting to throw out what has gone before instead of building on the past.

Read the whole thing here.

Thank you for reading! Please share Miller’s Book Review 📚 with a friend.

If you’re not a subscriber, take a moment and sign up. It’s free, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks, again!

My books are arranged chronologically as well, but fiction, biography, and Christian books, in addition to history.