Bookish Diversions: Do Audiobooks Count?

A Tale of Two Devices, Task Stacking, But Is It Really Reading? Plus: The Cigar Rollers’ Favorite Pastime

¶ A tale of two devices. Two digital devices debuted in 2007. One promised to revolutionize publishing but didn’t; the other made no such promises but still could.

When Jeff Bezos launched Amazon’s Kindle ebook reader, publishing pundits said it would completely upend the industry as digital distribution had done for music. Publishing would surely follow suit. Print would be reduced to a relic.

Ebooks began to gobble up market share almost immediately, growing by leaps and bounds. Initially. But then the trend hit a ceiling. While I was at Thomas Nelson I don’t recall ebooks ever exceeding a quarter of sales. The total probably stood lower.

Ebook sales actually peaked industry wide the year I left Nelson (2013) and have, according to stats compiled by WordsRated, been on the decline more or less ever since. 2020 saw a spike in sales, likely because of pandemic retail restrictions, but numbers are now back below where they were in 2018.

In terms of dollars, ebooks represent less than 7 percent of the entire U.S. book trade. Ebooks have their uses and their fans but hardly represent the publishing shakeup once forecasted.

But what about the other digital device that debuted in 2007? That’s the year Steve Jobs first held the iPhone aloft for the world to see. Not only have the iPhone and other smartphones bolstered the distribution of ebooks, thanks to a range of ebook apps, but they’ve also led to the explosion of audiobook sales.

When I first started listening to audiobooks in the 1990s, they were on cassettes, and I listened in my car. I can recall listening to Monty Python funnyman John Cleese narrating C.S. Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters. I also remember an audio recording of Lewis’s The Four Loves—in Lewis’s own voice. The real fun for me back then, however, was P.J. O’Rourke’s Parliament of Whores and Bachelor Home Companion.

I also listened to Hemingway, Tom Wolfe, and Bernard Cornwell on tape, but it was always catch-as-catch-can. Relatively few books ended up on tape or (later) CD. It was meh for consumers: The packaging was bulky, recordings often abridged, and the means to listen limited. And it was bad for publishers: The market was small, production costs high, and distribution difficult.

Then Steve Jobs put audiobook players in our pockets, solving both the consumer and publisher problems simultaneously. Through services like Audible, Apple Books, Scribd (now Everand) and others, audiobooks became a major format. With Spotify now joining the market, it looks to grow even more.

The audiobook shift took longer to come into its own but seems to have caught up to ebooks. The numbers cited by WordsRated don’t exactly add up. Audiobook sales in 2022, they say, topped $1.81 billion, while ebooks sat just a smidge ahead at $1.95 billion. The confusion? WordsRated also says audiobook sales represented 9 percent of all U.S. book sales that year, while ebooks represented just under 7 percent.

Let’s just say they’re about tied right now.

What’s important is only one of those formats shows any real sign of growth. Ebook sales are flat at best (they’re actually down over 16 percent in the last five years), while audiobooks are still on the upswing; projections anticipate audiobooks taking more than 20 percent of the market by 2030. Already, the New York Times reports, “For certain genres, like self-help and celebrity memoirs, audio sales can match or exceed print sales.”

Will this change upset the industry like digital music? Probably not. Will it be significant? It already is. And back in 2007 no one saw it coming, certainly not Jeff Bezos and Steve Jobs.

¶ Task stacking. One reason audio books have upward growth potential while ebooks don’t? The mode of engagement itself offers more opportunity. Roughy 70 percent of users report listening to audiobooks while undertaking other activities, such as driving (65 percent) and household chores (45 percent).

I listen while doing both, along with walking and exercising. It’s much harder to stack tasks when one’s eyes are glued to a page or screen. But with audiobooks you can do pretty much anything. “I listen while cleaning, showering, online shopping, exercising, getting acupuncture, sitting on long flights, and trying to fall asleep,” says Sangeeta Singh-Kurtz, writing in The Cut. “When I am alone—unless I am working, deep in REM sleep, or reading—I am almost always listening to an audiobook.”

Singh-Kurtz provides the perfect upside case of what audiobooks permit. Because listeners can stack tasks, they can read more. “I listen for hours and hours a day,” she says: “at a minimum, three; at maximum, 15. My average daily listening time is around four hours on weekdays and six hours on weekends.”

Of course, this is also where the tradeoffs of visual vs. audio engagement emerge at their sharpest. Task stacking divides our focus and can result in lower comprehension, especially for complicated texts. I cover the issue and the relative research here in depth. And cognitive scientist and reading expert Daniel Willingham weighs in with some helpful insights here and here as well.

But now we really come to it, don’t we? Up until that last bit, the operative verb I used to describe consuming audiobooks was listen. That’s what Singh-Kurtz used, too. Then I employed read and some of you probably winced.

Should you?

¶ Does consuming audiobooks count as reading? Some people firmly register no to this question. In The Gutenberg Elegies, for instance, Sven Birkerts says it’s more like passively watching television. “Our ear, and with it our whole imaginative apparatus, marches in lockstep to the speaker’s baton,” he says, utilizing another metaphor. “With the audio book, everything—pace, timbre, inflection—is determined for the captive listener. The collaborative component is gone; one simply receives.”

Daily Egyptian arts and entertainment editor Jeremy Brown is more forceful on the point:

If you say listening to an audiobook is “reading”—you may as well say watching someone else play a video game is playing it. You are not the one in the driver’s seat—you were there when the action happened but you didn’t do any of it—don’t take credit for it.

The form in which you absorb entertainment isn’t interchangeable between media, which is why listening to an audiobook, while having its own merits, is not the same as reading the book it’s based on.

That’s an interesting distinction, maybe even useful, no? For Brown the audiobook isn’t the book. It’s “based on” the book; it’s derivative. But that’s where I differ. As someone who has written, edited, and published books for over twenty years now, I would say the printed book and the audiobook are both the book—merely different forms of the same thing.

For what it’s worth, the royalties department would back me up. So would

. “Listening to a book counts as reading it,” she says,because it is a book. . . . A written text that is read or listened to is still a written text which uses language differently from language produced by oral speech. Think of conversation or even podcasts. No one says they “read” a podcast they listened to because a recorded informal conversation is not the same kind of text as a book or poem that is crafted by first putting words on a page or slate or screen.

A book is composed as a book. The fact that one listens to it is incidental to what it is; ergo, says Prior, using the verb read is perfectly acceptable, while she also admits it’s a mistake to equate reading with the ears and eyes.

English teacher and founder of the Twitter book club #CanonChat Matt Ryan agrees. “I say listening to audio books counts as reading,” he says but adds this qualification: “I strongly disagree with the philosophy that ‘all reading is reading’ if the implication is that all reading is equal.”

My reading of the research on audiobooks would back up Prior and Ryan. We engage texts differently through the ears than the eyes, but we’re still engaging a book—not, say, a podcast—and that’s why we can say we’re reading while listening to a narrator intone the sentences.

But now to argue against myself . . .

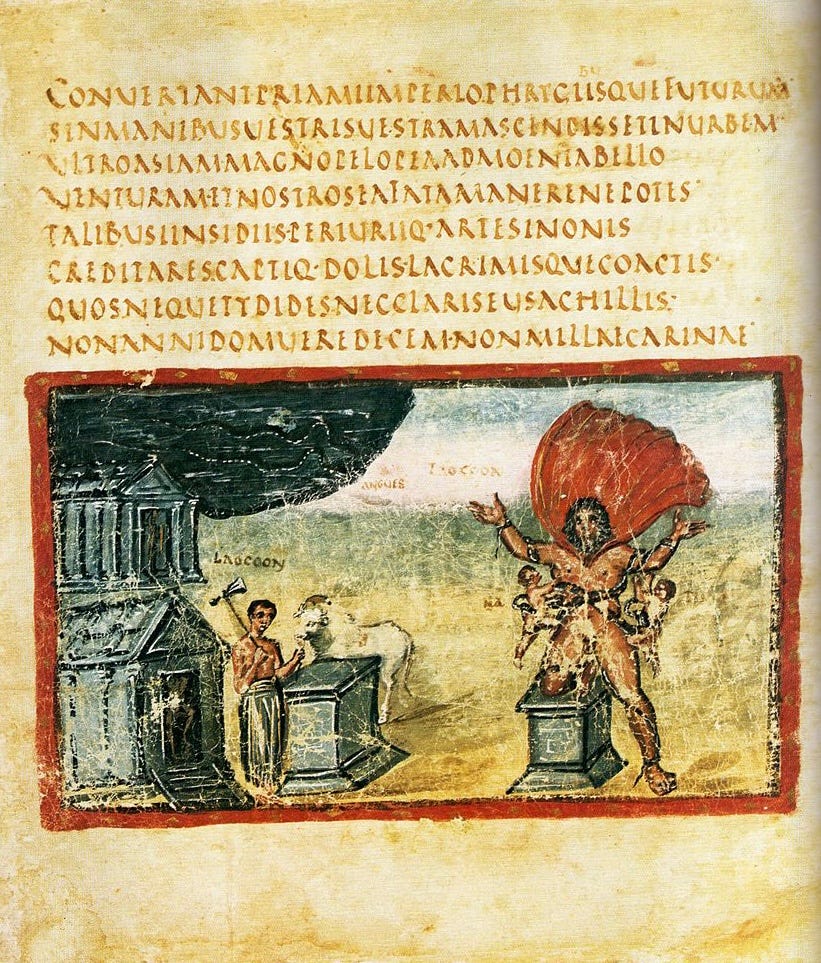

¶ Not all verbs are created equal. If you venture into the brightly lit corners of book history, you find that all books were once audiobooks. When, for instance, a Roman poet published a book, he’d so so by reading it aloud to an audience at an event called a recitatio—a recitation.

The practice went back to the Greeks. Herodotus recited his entire Histories at the Olympian Games and, according to Lucian, “bewitched” the audience and won universal acclaim. Herodotus had better luck than ninety-year-old Sophocles who supposedly died while attempting “to recite a fatally long sentence in a single breath” to a crowd gathered to hear his Antigone.

In a world before mass literacy and widespread distribution of books, most reading was an auditory event. This was true even for literate individuals reading on their own, though for another reason. The practice among ancient copyists, Greek as well as Roman, was to run all the letters INATEXTTOGETHERLIKETHIS. The style was called scripta continua and meant readers usually vocalized the syllables as they teased out the words.

Here’s precisely where I can say something positive for those who insist on distinguishing between listening to audio and reading print.

When silent reading came into vogue in the Middle Ages following the new practice of adding spaces between words, readers began to use different verbs to describe their activity. To read in the old mode was legere in Latin, which shares a root with our words legible and also select; it implied the act of reading meant picking out the syllables from a continuous river of letters.

But as Paul Saenger, the curator of rare books at the Newberry Library, points out in his history Spaces Between Words, word separation changed the act of reading enough that the verbs used to describe the activity followed suit. Instead of legere, readers were now said to videre or inspicere, to “see” or to “gaze.”

Word separation meant readers no longer had to vocalize the syllables to decode a sentence. Instead, they could simply see the distinct words and silently register them in their mind. And contra the point raised by Prior and affirmed by myself, this distinction emerged when there was no confusion about the format. A book was a book. The verbs depended not on the thing but the activity, a choice that would seem to parallel our distinction between listening and reading.

So, now that I’ve successfully backed myself into a corner, allow me to change the subject while simultaneously bringing all these threads together.

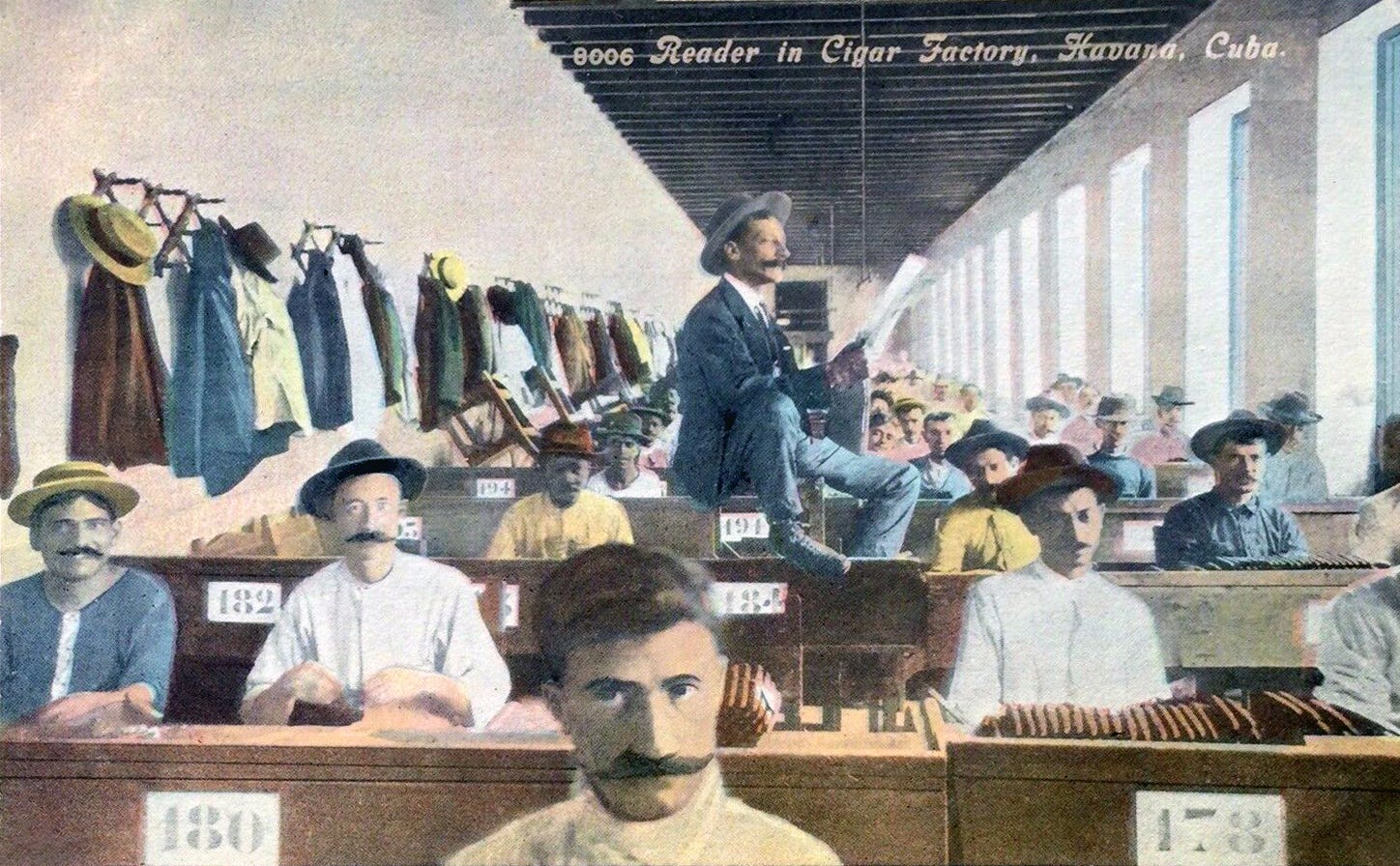

¶ Cigar-factory readers. Imagine sitting in a hot, humid room filled with smoke, monotonously rolling cigars all day long. Sound tedious, possibly terrible? Cuban cigar rollers—torcedores—agreed. So, beginning in the middle of the nineteenth century, they began pooling their money to pay for one of their numbers to stop rolling and start reading.

The role of el lector—and there’s that Latin word we already encountered, now serving as a noun, peeking through the Spanish—was to hold back the crushing waves of boredom by entertaining the rest of the crew with books, magazines, and newspapers. The practice caught on and became ubiquitous, migrating along with the trade to other locales, including Tampa Bay, Florida. It’s still a vital part of cigar manufacturing in Cuba.

Fifty-five-year-old Lara Reyes reads aloud to La Corona cigar rollers every day. She’s been at the job nearly thirty years. During the pandemic she mostly read news, but her preference is for novels by Victor Hugo and Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Torcedores prefer classic literature as well.

“By legend, at least,” reports the Associated Press, “cigars like the Montecristos and Romeo y Julietas owe their very names to books being read”—The Count of Monte Cristo, Romeo and Juliet—“as they were being rolled.”

In the story of the cigar factor lector we have the seemingly modern task-stacking benefits of audiobooks combined with the ancient practice of the recitatio. And I would imagine that the torcedores aren’t much concerned with whether it counts as listening or reading; they’re probably just grateful for a passage of The Last of the Mohicans while sorting and rolling some of the world’s most famous leaves.

What about you: Do audiobooks count as reading?

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Yes! And No! It doesn’t have to be absolute — just the same way as all reading isn’t the same in value. I don’t read the back of a cereal box at the breakfast table the same way I read an Eliot poem — but I use the same word to describe the action.

As I get more into audiobooks (my usage quadrupled last year), I am learning to distinguish between the books I want to habit-stack with, and the books I want to immerse myself in. The more complex fictional narratives are often ones I want to sit down, sit still, and simply listen to, or even, sometimes, read along in the physical book while listening — which is quite a marvelous experience!

But more than that: Audiobooks can be a true positive add for the reading experience. I’ve read Pride and Prejudice probably 15 times, but I’ve also seen the BBC miniseries, which came out when I was a teenager, 30 or 40 times. So whenever I read the book, I had those particular characterizations and actors and intonations in my head. Fine as the are, they aren’t Austen herself. The only way I broke the cycle and started to hear the author again was when I listened to an excellent audiobook production. It was unabridged, and voiced by one actor, but she did such a fine job inhabiting the voice of the narrator, that I could finally find Austen again.

I simply do not see the reason to be dogmatic about this. It’s a good thing. It may not be the very best thing, but it doesn’t take away from reading in any meaningful way, and can add to the experience and enjoyment of life as a whole.

(I *love* the cigar rolling lector story! Thank you for sharing!)

A perceptive article (as usual), Joel. My first response was to solidify the distinction between silent reading of a book, which of course is a fairly new phenomenon, and the passive listening to a book being read. The experiences seemed so different. But it's worth remembering as well that books serve purposes other than being read. They are more plastic tools than we think sometimes.

The purpose of the book read to children at bedtime surpasses words in the book, building bonds and love and helping a little one fall asleep (and letting mom or dad have some time of their own). I recall weeks of reading The Lord of the Rings to my three kids as we sat together on the sofa. I read with voices -- I do a pretty good hobbit and a wizard. Yes, a book was read. But the effect of the words resonated well beyond the story.

Such a fine post to read this morning!