Bookish Diversions: Book Robbers

Stolen Manuscript Returned after a Century, Store Shrinkage, Creative Theft, Book Borrowing, More

¶ Literary larceny. Bulgarian soldiers stole it from a Greek Orthodox monastery in 1917. It then traded hands over the decades until it ended up at the Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C. And what was it exactly? A medieval gospel manuscript with distinctive rubricated stars adorning the story of the woman caught in adultery.

Researchers used those unique markings to identify the book and return it last month to the Greek Orthodox Church. The New York Times covered the gospel’s restoration, and the Museum of the Bible published a lengthy and fascinating report detailing the manuscript’s long and winding history since it was first inked a thousand years ago.

This book isn’t alone in its status as stolen goods. Said His All-Holiness Patriarch Bartholomew back in 2020:

This Gospel manuscript was one of the 430 manuscripts and 470 religious objects stolen during this time that was unfortunately dispersed between various national and private collections through illegal proceedings and “legal” auctions.

If books such as these were subject to theft during World War I, it’s almost impossible to imagine the scale of theft and destruction in World War II—especially of Jewish books. I covered some of that in story in my review of The Library: A Fragile History. Another great book on the subject is Anders Rydell’s The Book Thieves, which details efforts to restore some of those books to their rightful owners.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free, and I’ll send you my top-ten quotes about books in your welcome email.

¶ Thou shalt not steal . . . unless it’s the Bible. Stealing Bibles is ironic on its face, given the Good Book’s many injunctions against filching, boosting, nicking, lifting, ripping, jacking, nabbing, heisting, and otherwise helping oneself to that which belongs to another. But it happens.

A couple decades back I worked as a clerk at Borders Books and Music in Roseville, California. Shoplifting was technically referred to as “shrinkage,” as in: inventory records say one thing but the count on the shelves reveals another. The real figure shrank compared to the paperwork, and the difference between the two figures was thus called shrinkage.

Bibles were by far our highest-shrink items. Every Bible was tagged with an alarm sticker and shrink-wrapped in clear plastic—a different use of the term that somehow seems doubly fitting. If a customer wanted to look at a Bible, a store employee had to remove the wrapping and stand there like an attentive mall cop until the browsing proved only browsing, instead of prelude to another tedious episode of CSI: Bookshop.

Precautions only worked so well, of course. As if to underscore various biblical messages about the fall, ancestral sin, and whatnot, I’d still find discarded cellophane wrapping bunched up and squirreled behind one of the larger art books, its former occupant gone . . . like a thief in the night, as it were.

¶ Growing up, I often heard that the medieval church used to chain up Bibles so average people couldn’t read it. It’s a common myth. The reality is that illiteracy was the norm, average people had better things to do than read, and books were only chained to keep clerics, monks, and visiting scholars from stealing valuable property—or reading in the latrine.

¶ Mental Floss has cataloged seven infamous book heists, including:

Hemingway’s early writing projects

Franz Kafka’s notebooks and letters

A copy of Shakespeare’s First Folio

An untitled Harry Potter prequel by J. K. Rowling

¶ If those incidents intrigue, here’s a quick rundown of some historical book thievery, including a medieval curse meant to ward off those with sticky fingers:

For him that stealeth a book from this library, let it change into a serpent in his hand and rend him. Let him be struck by palsy and all his members blasted. Let him languish in pain, crying aloud for mercy and let there be no surcease to his agony till he sink to dissolution. Let bookworms gnaw his entrails in token of the Worm that dieth not and when at last he goeth to his Final Punishment, let the flames of Hell consume him for ever and aye.

¶ Thieves get creative. Following a five year book-stealing spree, Geoffrey Talsma was sentenced in July to sixteen years in prison and ordered to pay Amazon $3,227,347.82 in restitution. How could someone possibly rob an online retailer of over $3 million in books?

“Talsma defrauded Amazon by using the internet to create numerous Amazon accounts and email accounts to rent textbooks and sell the textbooks for a profit when he should have returned the textbooks or paid the agreed upon buy-out price,” according to the U.S. Attorney’s Office.

To expand his reach and conceal the scheme, Talsma enlisted and paid “unwitting individuals” to receive stolen books on his behalf. Talsma eventually looped in some of these folks and began splitting the profits with his confederates. Part of the scheme involved ordering textbooks, claiming to have never received them, and then using the falsely acquired store credit to order more textbooks to sell. “The fraud scheme caused losses to Amazon well in excess of $3,000,000.00,” said the U.S. Attorney’s Office.

¶ Many possible motives. Talsma’s motive seems obvious enough: money. But you never really know, and some thieves are less conventional than others. The Italian Filippo Bernardini was arrested earlier this year in the U.S. He allegedly stole hundreds of unpublished manuscripts over the last five years using fake identities and phony email addresses. Why? No one really knows. But, says Stephanie Merritt,

I find myself hoping that Bernardini’s motive won’t be anything as banal as money. Ideally, he’ll turn out to be a rejected author seeking revenge or looking for a novel he can fillet and pass off as his own. . . . That’s what I’d go for if I were writing the inevitable film adaptation.

And we might have to wait for the movie because Bernardini may avoid trial in the U.S., according to one report. The case is on hold until later this week.

Update, March 24, 2023: After a bizarre court case in which the motive was never finally decided, Bernardini was found guilty. Though the judge ruled against jail time, Bernardini’s felony conviction would force him to leave the U.S.

¶ Some thieves don’t mean to steal. They just borrow. I have a book loaned to me about a decade ago by a man who has since died. Every time I look at it, I’m thrust into a moral conundrum. I take small comfort from the artist formally known as Eric Blair:

Book-giving, book-borrowing and book-stealing more or less even out. I possess books that do not strictly speaking belong to me, but many other people also have books of mine. . . .

—George Orwell

Indeed, I’ve loaned many books over the years that have failed to find their way home. How about you?

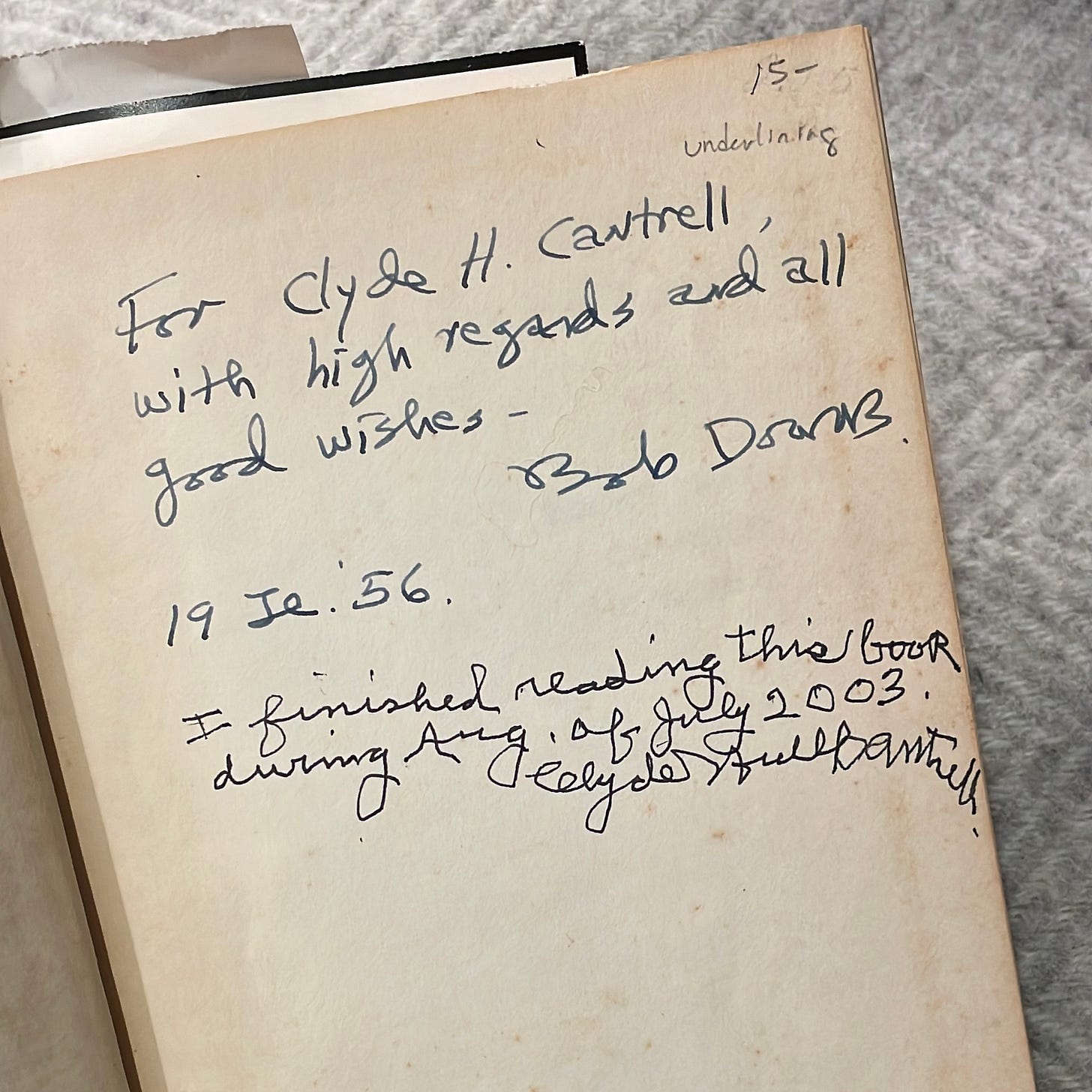

¶ Some readers steal time. If you ever worry about how long it takes you to finish a book, take heart. A couple years ago, I bought a copy of Robert Downs’ Books That Changed the World. The author gave this particular copy to a man named Clyde Cantrell and inscribed a note to him: “With high regard and all good wishes.” That was 1956.

Clyde took his time. Decades following the gift, he appended his own note to the inscription, stating he finished reading the book in 2003. That was almost fifty years after publication and receipt of the book and more than a decade since Downs had died.

¶ The struggle is, as they say, real. Click through for a great poem on watching cat videos instead of reading.

Thank you for reading! Please share Miller’s Book Review 📚 with a friend.

If you’re not a subscriber, take a moment and sign up. It’s free, and I’ll send you my top-ten quotes about books in your welcome email. They won’t improve your looks, but they’ll make you sound more interesting at parties. Thanks, again!