Bookish Diversions: The Bits We Usually Ignore

Dedications, Acknowledgements, Footnotes—and How I Handled Them In My New Book, ‘The Idea Machine’

When we think about a book, we usually focus on the primary text. But books have all sorts of ancillary stuff going on in the front, the back, and the margins. Sometimes we pay attention to it, other times not. But there are occasionally treasures in the bits we ignore.

¶ This one goes out to . . . Dedications typically follow the copyright page and sometimes even sit atop it when space is short. But author Jonathan Lethem says people are surprisingly incurious about them.

When it comes to his books, interviewers have asked Lethem about everything: the content, who endorsed it, the author photo, jacket design, and more. But not the dedication. Yet there are endless considerations in a dedication, he says. He offers some of the questions a dedication prompts in his mind, along with his own answers:

Why this person, how’d you decide, was it easy or hard? (Often hard. Sometimes easy.) Are you trying to apologize, or right a wrong? (There are better avenues for that.) Do you worry about fairness? (Hopeless to even begin.) Why dad, not mom? (I do love mom, but she’s gone, dad’s here. Dead-ications seem like wasted gestures.) Have you developed rules, as you go along dedicating books across the years? (The dedication should be to someone you could actually imagine enjoying the book in question.) . . . Is a book “to” or “for” someone, and why? (I prefer “for.” Nations dedicate themselves “to” causes or programs, scaring the s*** out of me. “For” feels more like the act of one person handing a book to another.)

Using very few words, dedications can speak many.

As it happens, I’ve dedicated my most recent book, The Idea Machine, to—not for, though I could gone that way just as easily—my daughter. “To Naomi,” it says, “our littlest reader.” Naomi is six and has begun reading on her own, which is a delight to see and a promise of so much to come.

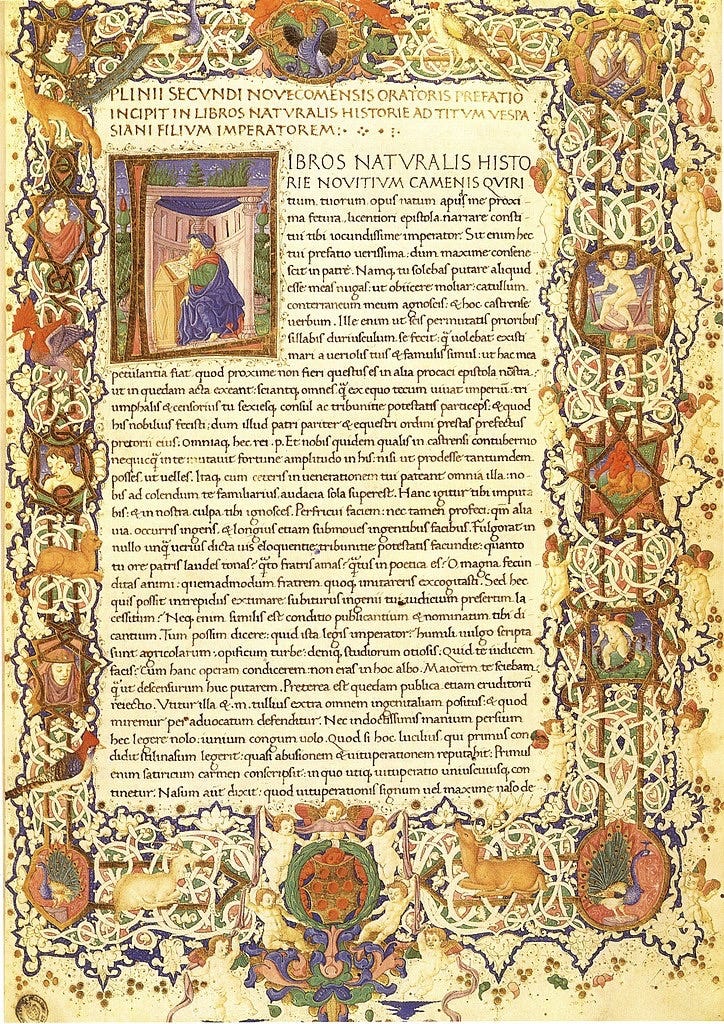

¶ A natural history of dedications. The practice of adding a dedication to a work goes back at least as far as the Romans. Pliny the Elder, for instance, dedicated his Natural History to Emperor Titus Vespasian. “This treatise on Natural History, a novel work in Roman literature, which I have just completed, I have taken the liberty to dedicate to you, most gracious Emperor,” he says before heaping line after line of obsequious praise on the emperor—which, I suppose, is the usual sort of praise one heaps upon an emperor.

Pliny wasn’t alone. Ancient and medieval authors dedicated books to patrons or potential patrons as a way either of publicly expressing gratitude for their support or boldly fishing for a job. Often these dedications took on the form of lengthy addresses. After all, one’s livelihood depended on the work’s reception—not by the public at large but, rather, by the the patron. Better smear it on thick.

By the time we get to the modern era, however, patronage was mostly out as means of support. Dedications hung on, but their meaning and length changed. Dedications mostly morphed into short expressions of gratitude or affection for one or more persons who contributed directly or indirectly to a work—good vibes or, as Ivan Doig says, quoted by Addison Rizer in a brief history of dedications, a “black and white valentine.”

¶ The pressure to get it right. Authors can feel a lot of pressure with a dedication. It may be “just some soppy, private transaction of the heart,” as novelist Tim Dowling says, but “a dedication is [also] meant to be a permanent memorial.”

There it is, isolated on its own page, singular, set apart, forever. But what if the author’s relationship to the dedicatee changes? I dedicated my first book to my first wife. The book had a better conclusion than the marriage; I now have mixed feelings whenever I see it. Likewise, Dowling mentions the case of Australian author Peter Carey, one of only five writers to win the Booker Prize twice, who caused a stir when he tried “to have all the dedications to his ex-wife expunged from future editions of his novels. . . .”

While I’ve only married one other woman, I have written several other books, and I’ve dedicated those to my love, my children, my parents, and my paternal grandparents. Why not my maternal grandparents? I might have subconsciously been following Lethem’s rule about the living and the dead.

Those choices are pretty typical, boringly so if we’re honest. “In a study . . . of 600 book dedications analyzed with 812 dedicatees,” says Rizer, “roughly 17% were parents, 8% were wives/husbands, followed by teachers, children, and friends.”

Philosopher Aaron James dedicated one of his books to his parents. The title? A**holes: A Theory. So, we’re left wondering, who was worse, Mom or Dad? Surely, that reading was unintentional. Then again, the joke is sometimes the entire point.

¶ Offered with a wink. For the clever, a dedication provides a place to express a bit of humor. For instance, Alan Stevens and James Lowe dedicate their rivetingly titled textbook Pathology

to the wine makers of Chateau Batailley (Bordeaux), Chateau Angludet (Bordeaux), Brown Bros Chardonnay (Australia), Robert Mondavi Cabernet Sauvignon (California) without whose help the preparation of this book could have been a real drag, and also to the Staff of the University Staff Club, University of Nottingham, who kept us cheerfully supplied with much of the above.

For their book, Nice Is Just a Place in France: How to Win at Basically Everything, the Betches comedy collective thanks “Xanax, for getting us through those anxiety-ridden meetings with publishers,” as well as “Adderall, without which we’d probably still be trying to figure out how to make a website.”

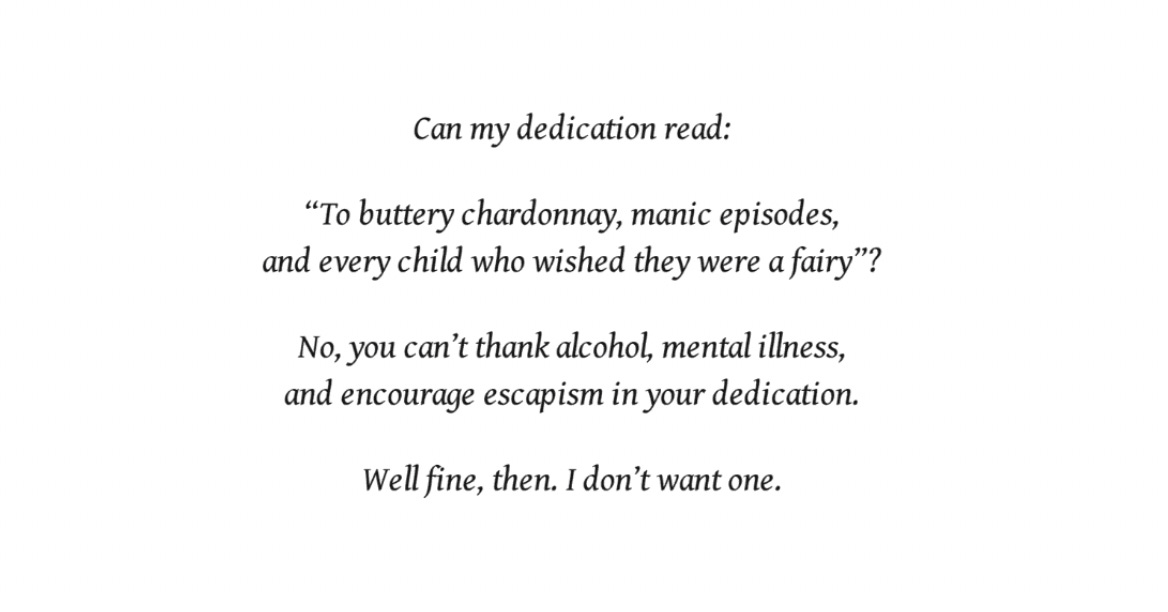

In place of a dedication, Piper CJ’s The Night and Its Moon features this possibly real, likely fake exchange between the author and . . . who? Maybe the editor:

Sometimes dedications subvert the form by undercutting the objects of their supposed affection with a passive-aggressive swipe. For his critically acclaimed memoir about his troubled youth, This Boy’s Life, Tobias Wolff offers a backhanded dedication: “My first stepfather used to say that what I didn’t know would fill a book. Well, here it is.”

Other times, the jab is more of a tease. P.G. Wodehouse dedicated Heart of a Goof “To my daughter Leonora without whose never-failing sympathy and encouragement this book would have been finished in half the time.”1 The same joke occurred to mathematician Joseph Rotman when dedicating An Introduction to Algebraic Topology:

To my wife Marganit

and my children Ella Rose and Daniel Adam

without whom this book would have

been completed two years earlier

Tim Dowling mentions Rupert Morgan’s playful dedication in Let There Be Lite. It’s similar to those by Wodehouse and Rotman but with a bit more bite: “Thanks to my adored wife, without whose unquestioning faith and support this book was nevertheless written.”

Actually, scratch that. Dowling says he falsely remembered it as a dedication; it was, in fact, part of the acknowledgements. What’s the difference?

¶ Credit and blame. Acknowledgements are designed to give credit where it’s due. No author writes a book utterly from scratch. Ideas come from other people, including other authors; as Cormac McCarthy told the New York Times, “The ugly fact is books are made out of books.” Acknowledgments give authors a chance to publicly state their dependence on the world beyond their favorite writing nook.

Sometimes expressions of gratitude are personal, such as Morgan’s. Other times they note the those individuals and institutions who supported the work. In this sense, we’re back to the classical and medieval period; we’ve just broken the dedicatory letter in two and placed some of it right after the copyright page in the form of the dedication and reserved some of it for later in the book in the form of the acknowledgments.

I had fun assembling the acknowledgements for The Idea Machine, though I tucked them under the more honest header of Thanks. Finishing a book brings a rush of gratitude for anyone who had a hand, however light, in the completion. I included people like my agent Andrew Wolgemuth, editor Jake Bonar, and friend Jeff Goins—all of whom believed in the book early on. I also included folks who reviewed chapters, others who provided atmospheric support, and my family. I was especially keen on including you, readers of Miller’s Book Review.

For me this concerns more than indebtedness; it’s about the joy of camaraderie in creation. As I conclude, “If I could have done it without you, I wouldn’t have wanted to.”

Acknowledgments can float; sometimes you’ll find them up front, other times in the back like mine. Whereever you might find them, I recommend reading them. Acknowledgments are a good way to understand more about where an author is coming from and the network of people and influences that helped birth the book. “Acknowledgments capture the real-life intimacies of the literary world and lay bare the backdrop of the writing process,” says Ayden Leroux.2

There’s also an art to well-done acknowledgements with perhaps even more pressure than a dedication. Writes Stuart Evers,

While I know the text is supposed to be the most important thing, and I’m well aware that the biographical details of a writer’s life should be incidental to the reading experience, the acknowledgement pages can have a subtle effect on the way I read a book. . . . I can’t help but slightly judge an author by the way they acknowledge their debts: too effusive and they seem a bit needy and try-hard; too brief—a list of names in alphabetical order—and you run the risk of appearing cold and dismissive. It’s probably the difficulty of treading such a fine line that makes me read long lists of names of people I have never met.

Writing is reading and researching, walking and thinking, speaking and silence, listening and questioning. Writing needs pleasure and relaxation, just as it requires the drudgery of the daily: emails, groceries, laundry, calendars. Writing needs the ache and élan of living that teaches us our own capacities and breaking points. Acknowledgments have the ability to expose that living.

I could rehearse several examples from authors I think have done it well—that capture the high-wire act of Evers or the elevated revelations of Leroux—but nah! Instead, let’s look at someone who breaks the form and delivers perhaps the greatest acknowledgments page of all time, B.M. Pietsch in Dispensational Modernism.

¶ Duly noted. Finally, let’s consider the footnote and their often-maligned siblings, endnotes. If acknowledgments give a reader a broad sense of how a book came together, footnotes and endnotes reveal the individual ingredients; they provide a peek into the source code. They also allow a writer to add observations or share details that warrant attention but don’t quite fit within the flow of the text.

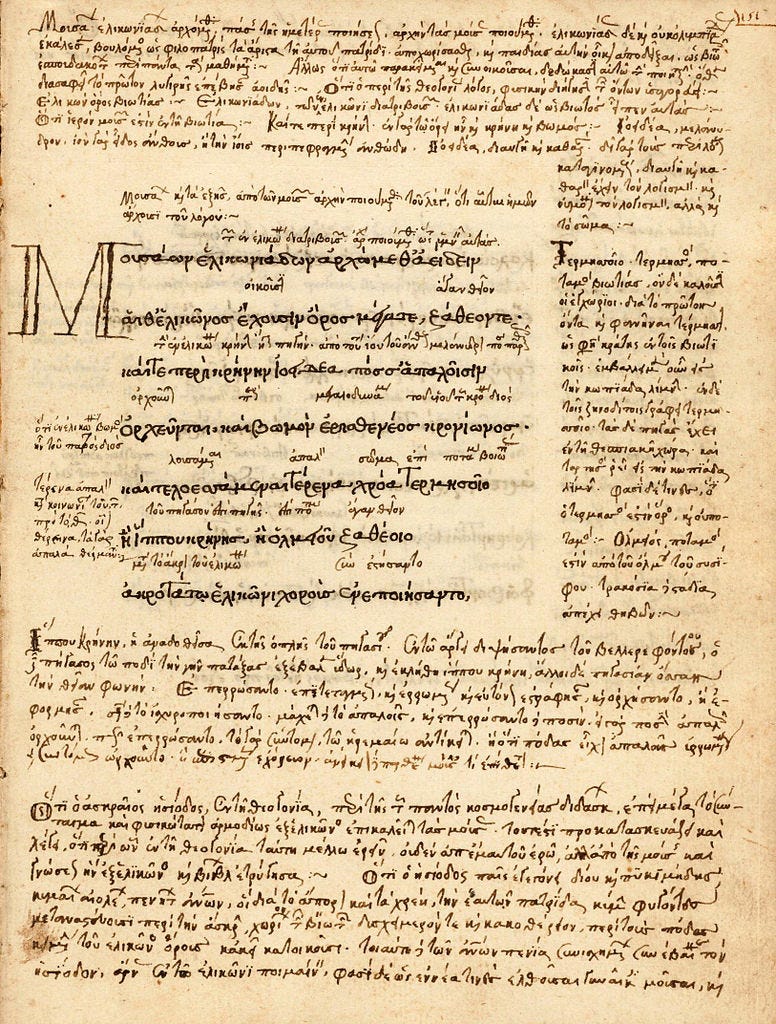

As with dedications, including supplemental notes alongside the main body of a text goes back a long way. We find in medieval manuscripts, for instance, scholia and other forms of commentary arranged in the margin around the main text—as with this sixteenth-century copy of Hesiod‘s Theogony, ringed with commentary by John Tzetzes.

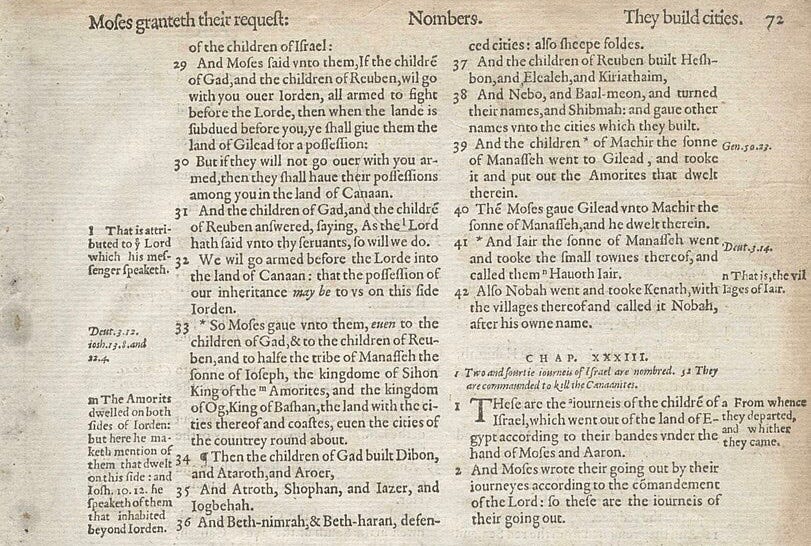

But it’s a stretch from surrounding a text with an invading army of opinions to the sort of ancillary sort of discrete observations and source acknowledgment we recognize today. You can see how we got there, however, by looking at transitional forms, such as this page from the Geneva Bible, an early English translation especially valued—and, depending on the audience, loathed—for its notes.

¶ At the bottom or the back? Taken individually, footnotes can shed light on a writer’s scholarship. Taken collectively, however, they help tell the history of scholarship itself and even that of the publishing business. For instance, what do we make of the shift from footnotes, which sit directly below the primary text and endnotes which shunt all that erudition to the rear of the book?

“The decline of the footnote has been linked to changes in the publishing business,” says Bruce Anderson, referring to the trend back in 1997.

College libraries, corseted by budget squeezes, are no longer the principal buyers for the books produced by some academic presses. These books are now packaged to attract a broader audience, the [New York] Times says, with ”catchier titles, snappier covers, more and better illustrations and fewer footnotes and bibliographies.”

Some books have dropped the annotations altogether and others have simply moved them from the bottom of the page to the end of chapters or the back of the book where they are properly called endnotes.

A certain kind of reader will howl at this move. I get it. Flipping to the back is particularly annoying when reading a text for which the notes are an essential part of the experience. Noel Coward complained that reading footnotes is like “having to go downstairs to answer the door while in the midst of making love.” With endnotes it’s more like walking to the end of the driveway.

Then again, excessive notation can clog the text and slow the reading experience. By relegating the noise to the back, endnotes permit a more fluid reading experience. Life is, alas, nothing but tradeoffs.

¶ Numbers, symbols, page references, what? Then there’s the question of how to indicate noted material. For footnotes, you can go with numbers or superscripted symbols—say, a dagger, dot, or asterisk.

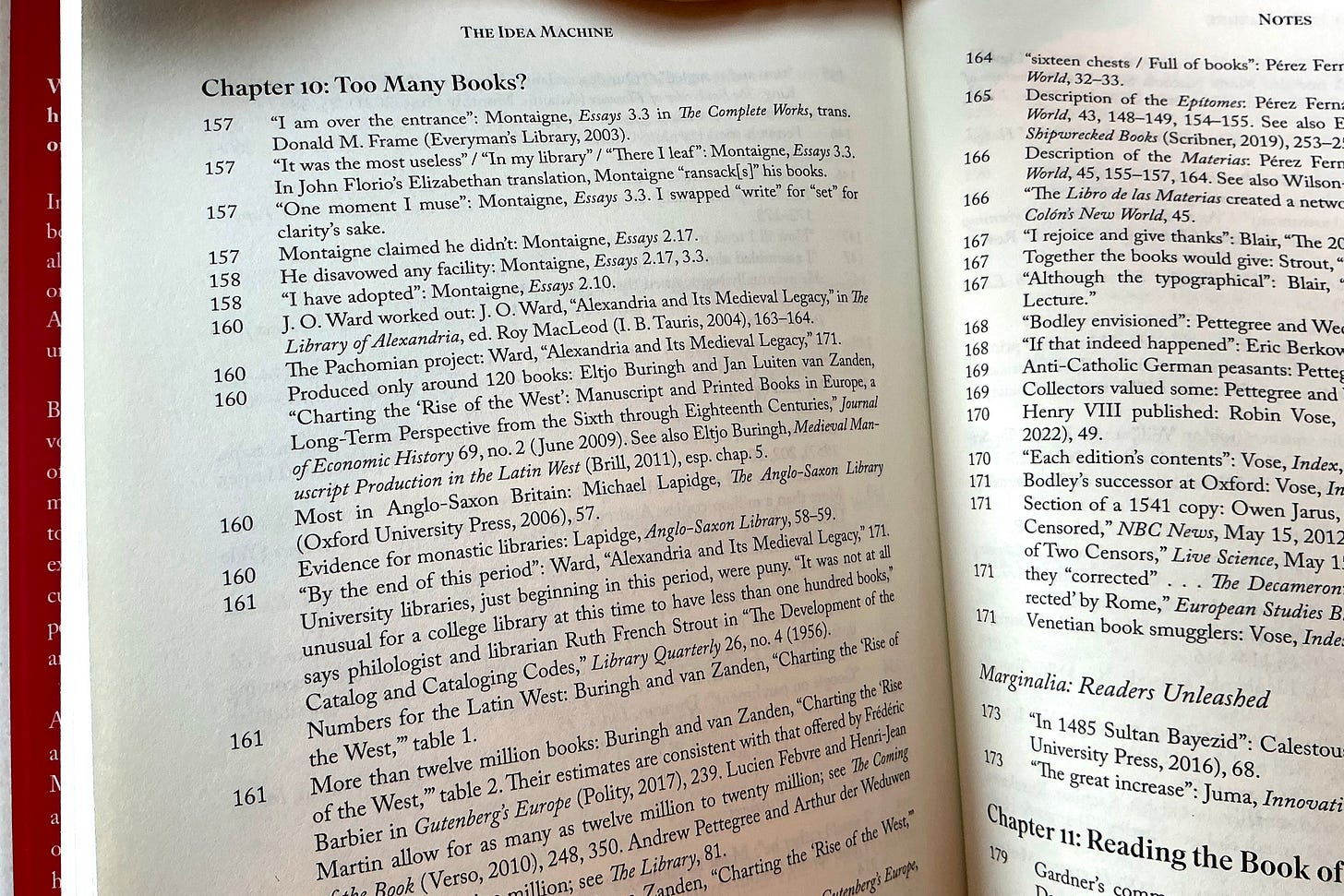

Endnotes tend to utilize numbers, but for The Idea Machine I opted to follow the advice of my editor; he suggested we use another format, echoing snippets of text in the back sortable by page number, like so:

I’ve seen countless other nonfiction books follow this method, but this is the first time I’ve used it myself.

¶ Make it count. I’ve written four books at this point. For kicks, I added up the number of endnotes in each. Here’s the breakdown:

Bad Trip (2004): 587 notes

Size Matters (2006): 322 notes

The Revolutionary Paul Revere (2010): 522 notes

Lifted by Angels (2012): 414 notes

The Idea Machine (2025): 569 notes

That’s a total of 2,414 notes with an average per book of 483. “The ugly fact is books are made out of books”; it’s helpful to say which ones.

¶ Snide aside. Footnotes also provide the perfect place for the snide aside. Take a famous example from Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. In the main text, Gibbon makes a winking, oblique reference to the claim Origen of Alexandria had castrated himself. “The primitive church was filled with a great number of persons of either sex, who had devoted themselves to the profession of perpetual chastity,” he says. “A few of these, among whom we may reckon the learned Origen, judged it the most prudent to disarm the tempter.”

Gibbon can’t resist a gibe, so to that last bit he appends a footnote both citing Eusebius as the source for the mutilative detail and to nudge the joke a bit further. “As it was his general practice to allegorize scripture,” he says, “it seems unfortunate that, in this instance only, he should have adopted the literal sense.” He trusts the reader knows the passage in question—Christ’s advice to pluck out one’s eye and lop off one’s hand if they lead an individual to sin.

In Flash Boys, journalist Michael Lewis offers another example, less snide than merely humorous.

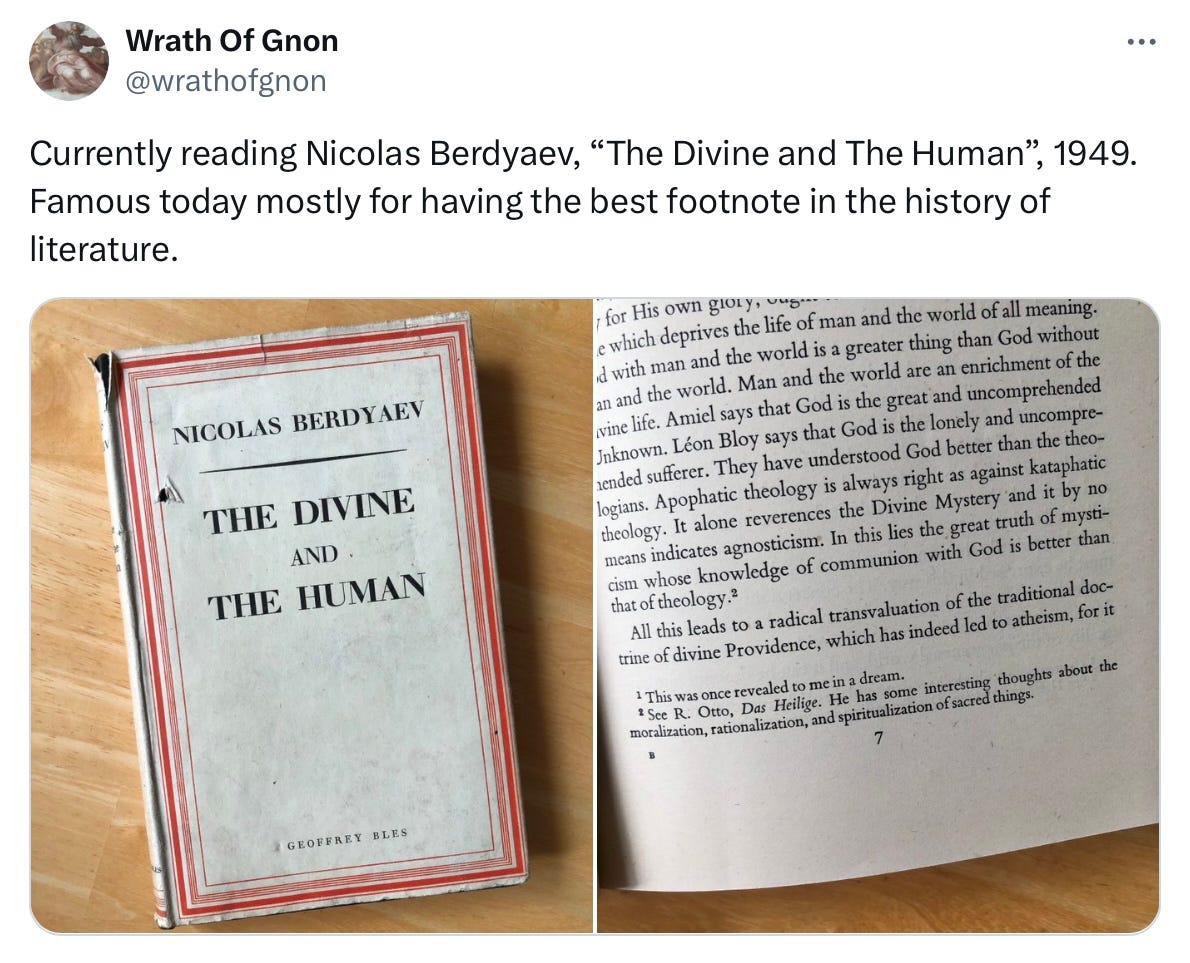

¶ Revealed in a dream? Normally, authors cite their sources to (a) let readers know where they got their ideas and (b) point us to those sources so we can check them ourselves. Sometimes (a) is frustrated by incompleteness; whereas (b) might be frustrated by the obscurity or inaccessibility of the sources.

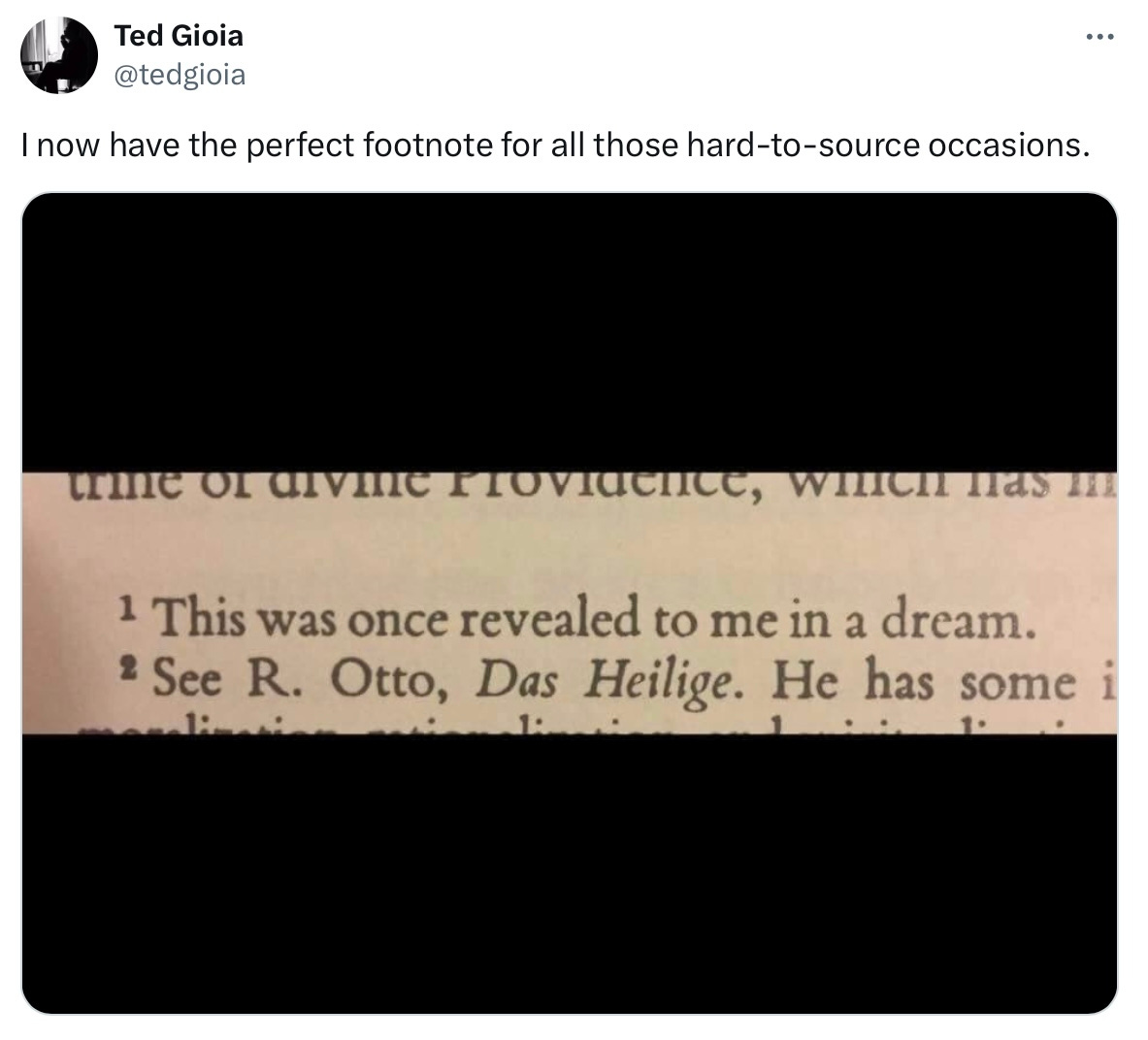

Nicolas Berdyaev gets the prize for frustrating both (a) and (b) while providing one of the most delightful footnotes in publishing history. See note 1 below from page 7 of his book The Divine and the Human: “This was once revealed to me in a dream.” Oh, was it now?

The quote lives on in a bizarre and nichey afterlife. I’ve heard of people hunting down copies of the 1949 book just for the footnote. You can find it on memes. And, should the mood strike, you can buy a sticker of the note to adorn whatever you desire.Ted Gioia approves.

Giles Slade offers a much less daring—though equally enjoyable—endnote of a hard-to-source tidbit in American Exodus: Climate Change and the Coming Flight for Survival. The best part? He mentions the keywords by which a person might find the elusive article while announcing he can’t be bothered to do so himself.

This figure is from a New York Times article of the period, and will probably show up if you search keywords for “Barge Captain,” “1258 dead horses,” or “Barren Island,” in ProQuest Historical Newspapers. I’ve lost the bloody reference, and am confessing my carelessness to the world instead of spending the day looking for the exact piece. Perhaps you could just trust me on this one. If you can, then I thank you.

For what it’s worth, I tried the New York Times archive and couldn’t turn up anything.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

While I usually rely on hyperlinks to note my sources, there wasn’t a good place to note I got the Wolff and Wodehouse examples from this enjoyable article by Sloane Tanen.

If you’re an author, acknowledgements are also a great way to find out which agents and editors are working on books like yours.

I have quite a few footnotes in my first published non-fiction book, but you have to have a lot to show that you did research and that you used it well.

A medieval author could also be simply fishing for money. Christine de Pisan is useful here as a datum, because most authors had other jobs. She just wrote. One book a year, and she was able to support herself, her mother, her sister, and her children, on the gifts from those she dedicated them to.