Gag Order: The Limits of Free Speech

Reviewing Eric Berkowitz’s ‘Dangerous Ideas’ and Richard Ovenden’s ‘Burning the Books’

The aphorist tells us knowledge is power. So what happens when powers conflict? Novelist Salman Rushdie now bears one of many possible answers to that question in knife wounds suffered last week during a public appearance. More than thirty years ago, Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini ordered Muslims worldwide to kill Rushdie for blasphemous material in The Satanic Verses, a novel the cleric had probably never read.

Thankfully, Rushdie’s attacker failed, and the writer is recovering. Others have fared as bad or worse since the ayatollah’s fatwa; those connected to the book worked with targets on their heads. “The book’s translators were stabbed, shot, or killed in Japan, Italy, and Norway,” according to journalist and lawyer Eric Berkowitz. The fatwa has led to “nearly two dozen deaths, scores of injuries, and the firebombing of bookshops.”

Much of the western world has rallied behind Rushdie, now as well as when the fatwa was originally issued. To the extent that seems like an obvious choice shows how thoroughly the value of free speech has burrowed itself into western thinking—and in relatively little time, as Berkowitz shows in his fascinating history of censorship, Dangerous Ideas.

Berkowitz takes his narrative all the way back to the Hebrew injunction against graven images of the divine and moves quickly through subsequent attitudes about speech: ancient Greek and Roman, medieval and modern European, and American.

In the ancient world, nobody had qualms about destroying books. The Sophist philosopher Protagoras doubted humans could know whether the gods existed and said as much in his book, On the Gods. He was hauled before a tribunal in Athens and convicted of impiety in 430 BCE. Protagoras either fled before the trial or was exiled. Either way, Athens wanted him gone and supposedly burned his books to expunge any trace. “If that indeed happened,” says Berkowitz, “it was likely the first book burning in Western history.”

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free, and I’ll send you my top-ten quotes about books in your welcome email.

When the power of knowledge conflicted with the power of the state or its religious prerogatives, authorities tried snuffing the knowledge out. While Julius Caesar gave critics wide berth, his successor Augustus was brutally repressive to dissenting views and those who held them. He burned thousands of books by freelance astrologers and soothsayers. He also targeted critical writers and historians. Titus Labienus watched all his books go up in flames before he committed suicide. One orator who bragged about memorizing Labienus’s books had his own books burned before being exiled—twice.

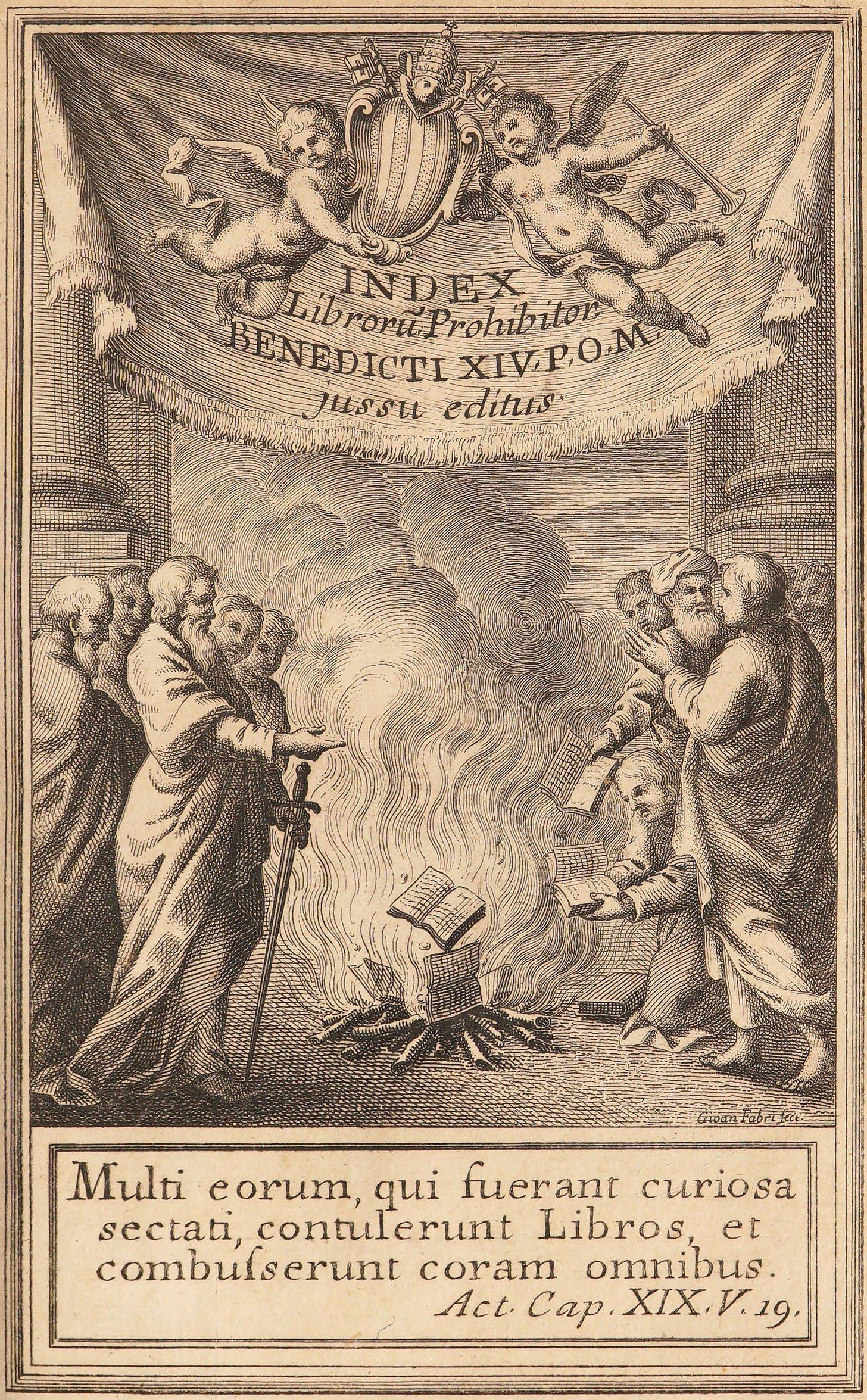

Emperor Diocletian’s Great Persecution of 303 targeted Christian books for destruction. Christianity undercut adherence to Roman rituals. Authorities believed those rituals safeguarded the community. As Christian numbers grew, they became a threat to societal stability. Officials recognized the reliance of Christians on their books and considered destroying church libraries a prime tactic in curbing the faith. It didn’t work.

Regrettably, Christians turned to repression themselves when it suited. “There is an unjust persecution which the wicked inflict on the Church of Christ,” said Augustine, rationalizing the move, “and there is a just persecution which the church of Christ and inflicts on the wicked.” Berkowitz follows this unhappy trajectory through the Middle Ages, a period that deviated little from prior centuries.

Change eventually came in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in response to what Berkowitz calls the “printquakes” of the time. If knowledge is power, printing represented a massive expansion and redistribution of it. Suddenly, political and religious authorities found themselves unable to fully suppress dissident voices.

The religious realignments of the Reformation gave birth to limited conceptions of the liberty of conscience and expression. While the Catholic Church attempted to regulate publishing and prohibit offending books, and Protestants destroyed monastic libraries, using breviaries and service books in latrines, select voices began calling for freedom of speech. Berkowitz points to the Levellers, who opposed censorship, and John Milton’s 1644 defense of free speech, Areopagitica.

Many of these pro-speech advocates, however, argued against extending the right universally. Berkowitz cautions about our judging them too harshly. “There was no tradition in the seventeenth century of supporting total freedom of expression,” he writes. The rules guiding and regulating technology normally come along gradually as the technology is deployed and use-cases multiply. It’s the same with free speech.

For those unfamiliar with the record of the American tradition, this might surprise. Many of the same founders that approved the First Amendment to the Constitution, guaranteeing free speech, also supported the 1798 Sedition Act which criminalized dissent. And the same thing happened in France, where freedom of speech was enshrined in 1789 before being overturned in 1792, when dissenting books were burned and their authors killed.

The nineteenth century was every bit as baffling, as the U.S. post was employed to squelch abolitionist literature, preserve the fragile self-image of slaveholders, and prevent civil unrest. Hot-and-cold attitudes persisted into the twentieth century as censors found all sorts of reasons to snub this or that book. The case of James Joyce’s Ulysses is famous, but what about Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland? Censors banned Lewis Carrol’s children’s book for its supposed promotion of masturbation and substance abuse. Wouldn’t every child want a hookah after encountering the smoking caterpillar?

“Unless a right is absolute, its reliability ceases,” says Berkowitz. Universally free speech never obtained until the second half of the twentieth century, and even then it’s experienced some shaky moments. The brutal totalitarian overreach of the Nazis and Soviets probably did more to cement the sacredness of free speech than anything. Their actions, so starkly contrasting with western notions of liberty, helped define and absolutize western appreciation of the right.

That postwar commitment, however, seems vulnerable these days. Berkowitz points out one key change among many:

Who, after all, would have imagined even a decade ago that a private tribunal assembled and financed by a thirty-six-year-old billionaire's company, Facebook, would have the power to pass judgment—on a transnational basis—on some of the day’s most important speech issues?

The rise of private platforms playing host to public speech is our century’s version of the “printquake” and raises issues our norms and laws did not evolve to address. This is a different sort of power conflict, one which doesn’t involve force so much as potentially misaligned interests between the involved parties.

Richard Ovenden, director of Oxford’s Bodleian Libraries, finds this change troubling and addresses it in his historical study of the destruction of knowledge, Burning the Books.

Ovenden takes a wide view, going back to ancient Nineveh and the destruction of Ashurbanipal’s massive library. From there he moves to Alexandria’s famed lost libraries. And yes, that’s plural; there were two of them. Readers may find overlap with Andrew Pettegree and Arthur der Weudwen’s exhaustive and valuable book, The Library: A Fragile History. Ovenden’s unique eye for telling details and the brevity of his treatment warrant attention nonetheless—especially when turned to a key question of his study: If knowledge is power, what responsibility do individuals and societies have to steward it?

Archives and libraries form the memory of civilizations. If records and their subsequent interpretations are lost, we move through the world like amnesiacs who can’t remember our last breakfast or what we’re doing moment to moment and why.

The intentional destruction of archives and libraries have long played a part in decapitating communities, even whole societies. When the Seleucids wanted to lord it over Jerusalem, they desecrated the temple and destroyed the library the governor Nehemiah established centuries before. When Judah Maccabee regained control, he cleansed the temple and rebuilt the library (2 Maccabees 2.13–15). By then the books were nearly as important as the altar; eventually, they would surpass it.

Sometimes individual authors and other historical figures want their work and papers destroyed; other times people in their circle desire the destruction. Novelist Franz Kafka insisted that his papers be burned. His final request was denied after he was no longer around to argue, as Ovenden recounts. Others, however, succeeded in sending legacies up in smoke. Cromwell’s staff incinerated his papers to eliminate incriminating evidence after his fall from grace in 1540. Lord Byron’s memoirs were burned because people close to him found them scandalous.

Libraries and archives today house incredible amounts of data, but space constraints persist and curators must make decisions on what to keep and what to let go. Ovenden describes the (usually) careful way such decisions are made. But singular information sometimes slips through the cracks, lost forever. Digitization efforts prevent some of this loss but open up other questions—not least, who owns the digital record and how reliable is it?

As information originates on digital platforms, how should that be preserved? Public officials live on Twitter; shouldn’t their feeds be archived? How? By whom? Available to whom? The ownership question raises its head again here as well. As with Berkowitz’s concerns over censorship, our norms and practices around preservation lag behind our technology.

Ovenden highlights five key functions of libraries and archives worth pondering. Libraries and archives:

assist mass and special education;

protect diversity of knowledge;

advance an open society and protect citizen rights;

provide a fixed reference point to verify truth claims; and

establish cultural and historical identity.

The world’s a better place when there’s a record to check. If societies attack that knowledge, whatever its nature, through censorship; lose it through neglect; or, worse, expunge it on purpose, we lose something of inestimable worth. Given how recently our commitment to free speech emerged, it’s probably more precarious than any of us want to admit.

Thanks for reading. If you’re enjoying Miller’s Book Review 📚 please spread the love and share it with a friend!

And if you’re not a subscriber, take care of that now. You’ll be glad you did.