Declaration of an Independent

Self-Made Man? Reviewing the ‘Autobiography’ of Benjamin Franklin

As a young man, Benjamin Franklin grew up surrounded by words. He worked in a print shop, and his father made books available in his home—though not always the selections young Ben desired. Despite this literary foundation, however, learning to write proved just as accidental for Franklin as its example proves telling for his readers.

As Franklin recounts in his Autobiography, circumstances interrupted an adolescent debate with a friend and the two were forced to resume the discussion by letter. Franklin’s father chanced upon the missives, read them, and told his son he showed real promise, even if his style was a bit crude.

Encouraged by the praise and determined to remedy the deficiency, Franklin, the consummate autodidact, acquired a copy of Addison and Steele’s Spectator and learned to imitate its more elevated style by various self-concocted exercises, including rewriting the essays from memory:

I took some of the Papers, & making short Hints of the Sentiment in each Sentence, laid them by a few Days, and then without looking at the Book, try'd to complete the Papers again, by expressing each hinted Sentiment at length & as fully as it had been express'd before, in any suitable Words, that should come to hand.

Franklin then compared his version against the first, critiquing his effort. One detectable gap? He lacked a large “Stock of Words.” But no worries. He figured he could improve his vocabulary by rendering the prose into poetry, a move which would force him to learn a diverse array of new terms.

Franklin not only turned the stories into poems, he next let his memory of the original fade before turning the poems back into prose. The gold produced through this literary alchemy was the improvement of his style and mastery of expression. Nor were these his only tricks.

I also sometimes jumbled my Collections of Hints into Confusion, and after some Weeks, endeavor’d to reduce them into the best Order, before I began to form the full Sentences, & complete the Paper. This was to teach me Method in the Arrangement of Thoughts. By comparing my work afterwards with the original, I discovered many faults and amended them; but I sometimes had the pleasure of Fancying that in certain Particulars of small Import, I had been lucky enough to improve the Method or the Language and this encourag’d me to think I might possibly in time come to be a tolerable English Writer, of which I was extremely ambitious.

Of course, his hunch proved true. Through the subsequent decades Franklin emerged as one of the most prolific among the American founders. What’s more, he remains among the most colorful and quotable. We might stumble over the now-archaic spelling and grammatical conventions, but Franklin’s readability not only impressed his contemporaries, it persists to the present.

What stands out most of all in this account, however? Franklin’s self–determination and self-directedness.

Self-Read Man

Franklin is often credited with the appellation of the first self-made man. The reason owes almost entirely to his Autobiography and its routine depictions of his independent streak and idiosyncratic approach to life.

Reading played a large role in his development. Coming upon a book praising the virtues of vegetarianism, Franklin decided as a teen to forswear animal products, much to the bafflement of his family and associates. Unshaken, Franklin pocketed the money saved by the practice. “This was an additional Fund for buying Books,” he said, also benefitting from the time saved trudging back and forth from a boarding house with his coworkers for lengthy meals. He used the found time for additional reading.

Raised Presbyterian, Franklin abandoned the tradition when given books arguing against deism; spread out on the page, the deist arguments struck him as more compelling than the orthodox. While Franklin held a belief in God and his providential concern for his creatures, he otherwise shed any allegiance to the usual creeds. Amid clamorous sects asserting the rightness of their belief, Franklin fashioned his own creed, something that transcended the squabbles and harmonized what he deemed beneficial among their competing claims.

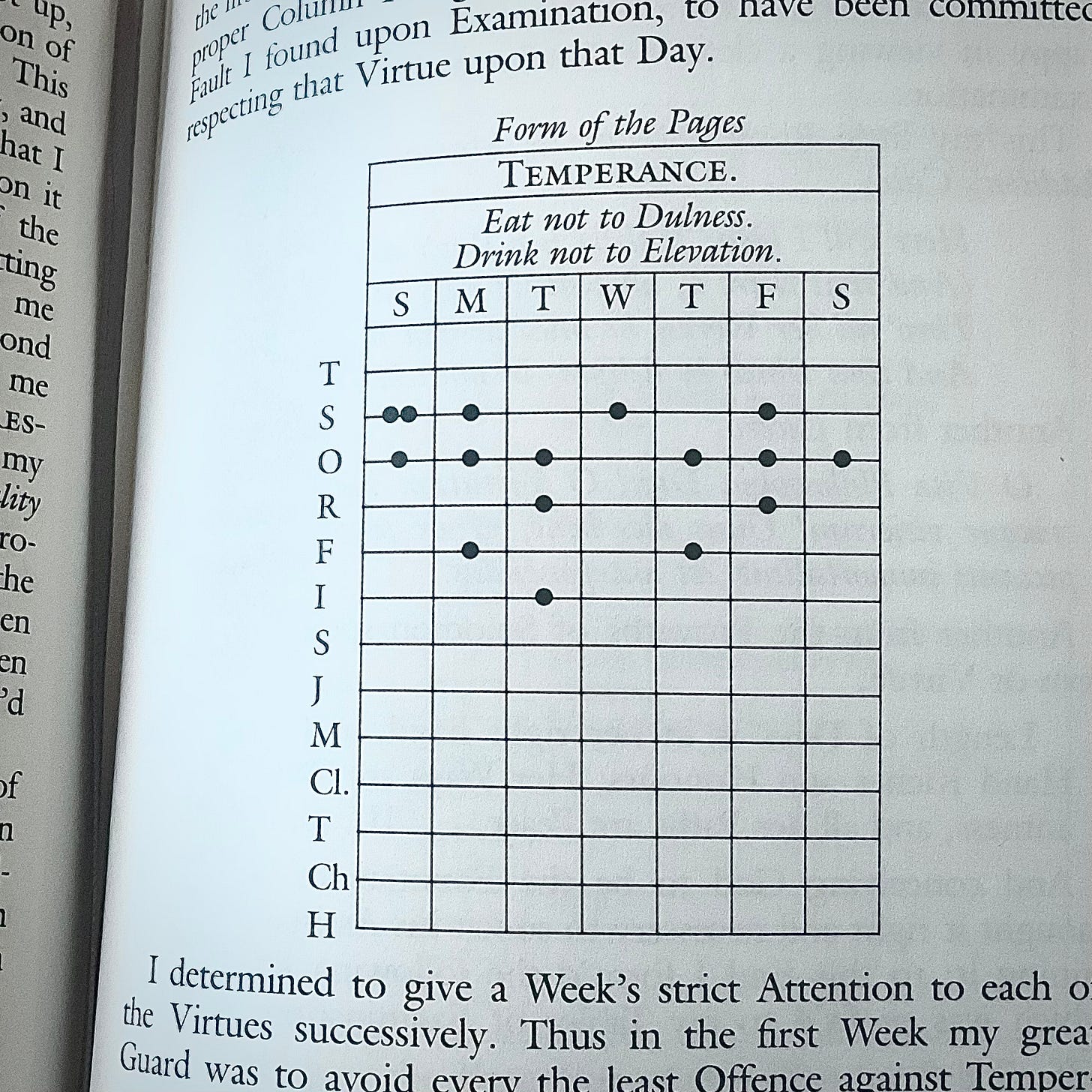

Franklin’s bent toward self-determination also emerges in his famous scheme for moral improvement, what he calls his “bold and arduous Project” for “moral Perfection.” In true self-fashioning style, Franklin developed his own list of a dozen virtues—temperance, industry, justice, tranquility, and so on—along with a working definition for each. He then created a set of tables to track his daily progress toward their attainment.

Somewhat humorously, a Quaker friend pointed out that Franklin seemed to struggle with pride. Naturally, Franklin stretched his list to embrace a thirteenth virtue, adding humility with the injunction to “Imitate Jesus and Socrates.”

Despite the Quaker’s critique, daily observing his behavior engendered a remarkable level of self-awareness. “I was surpris’d to find myself so much fuller of Faults than I had imagined,” he admitted, confessing particular trouble with the virtue of Order—that is, the proper prioritization of time and other resources. Attempting to tackle this virtue led him to create a detailed, hour-by-hour daily schedule, thus securing his status as the godfather of planning and productivity (something for which I’m personally grateful as the chief product officer of Full Focus, creator of the Full Focus Planner).

His Own Man, of Use to Others

Such episodes track with the general thrust of the narrative. For the entire reach of his life, Franklin was intent on living life by his own lights and for his own reasons. Apprenticed to his brother, James, the printer, Franklin smuggled essays into James’s newspaper using a pseudonym. He then used a loophole in their arrangement to quit his indenture early and leave for better opportunities elsewhere.

He traveled to New York and then Philadelphia looking for work in a printing house. Eventually he made his way to London, all the while he stood out from his peers either by his excellence or his eccentricity; his vegetarianism and abstention from drink put him at odds with his coworkers who sometimes teased him by playing havoc with his workstation.

But however independent and individualist his bent, Franklin likewise found a powerful motivation in public service. The two are not mutually exclusive. Back in Philadelphia, while he labored to establish his printing business, he concocted a fire-prevention scheme for the city, built a subscription library, established a school, served in several public offices, and more.

In the early 1740s, he designed an open stove “for the better warming of Rooms, and at the same time saving Fuel. . . .” Franklin’s design, eventually named after him, proved a significant innovation, but surprisingly he declined a patent when offered one by the governor:

I declin’d it from a Principle which has ever weighed with me on such Occasions, viz. That, as we enjoy great Advantages from the Inventions of others, we should be glad of an Opportunity to serve others by any Invention of ours, and this we should do freely and generously.

Similarly, public service played a role in Franklin’s famous experiments with electricity. Curiosity drove him at the start. In 1746 he witnessed electrical experiments in Boston, and shortly thereafter his library in Philadelphia received a glass tube with documentation for making experiments of his own, which Franklin conducted over the next several years. During this period, Franklin determined lightning was a form of electricity and famously attracted lighting in a storm by flying a key from a kite.

Part of the burgeoning Enlightenment, Franklin saw experimental science as advancing human knowledge. But it could have immediate practical application as well—as when Franklin realized lightning rods could prevent homes from catching fire in storms. Still, there were tradeoffs.

When another scientist disputed his electrical theory, Franklin decided to let his published papers speak for themselves, along with whoever might replicate his findings and take up his cause.

I concluded to let my Papers shift for themselves; believing it was better to spend what time could spare from public Business in making new Experiments, than in Disputing about those already made.

Scientific research is fundamentally speculative and its findings uncertain. So if Franklin was going to spend time away from more immediate public service, he would spend his scarce time on research, not disputes. Sounds as though he mastered the virtue of Order after all.

No one is truly self-made. But some people are more conscious than others of the personal determinations we make in shaping our decisions, character, and contribution to the world around us. From the outside that awareness manifests as independence and sometimes arrogance, especially when it runs counter to norms and expectations. But Franklin’s Autobiography reminds us that the world is—and we as individuals are—generally better for it.

The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin was the first book in my classic memoir goal for 2024. Here’s what’s in store for the rest of the year:

January: Benjamin Franklin, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin

February: Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass

March: Richard Wright, Black Boy

April: Maya Angelou, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings

May: Tété-Michel Kpomassie, Michel the Giant: An African in Greenland

June: John Steinbeck, Travels with Charley

July: Stephen King, On Writing

August: Zora Neale Hurston, Dust Tracks on a Road

September: Ernest Hemingway, A Moveable Feast

October: John Stuart Mill, Autobiography

November: C.S. Lewis, Surprised by Joy

December: Beryl Markham, West with the Night

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related posts:

Great review Joel. I have not read this one. I did read the biography of Franklin written by Walter Isaacson which was excellent and I found Franklin to be a fascinating individual. He certainly did not conform to the mold or expectations of his era.

I found it interesting to read what you wrote of Franklin‘s account of leaving Boston by virtue of a loophole in his contract with his brother. I had heard that his brother resented Franklin’s success with his Silence Dogood letters, and so his brother began mistreating him. Franklin fled and lied to a ship boat captain that he had gotten a girl pregnant and needed to flee the city. Maybe all of this harmonizes, I had just never heard about the loophole. Wonderful summary of this book, Joel. It’s amazing how rationalism took such deep root that it led greater support to the error of deism. Such misdirection by such brilliant men makes me often wonder where we are off today.