Russian Roulette: The Woman Who Bet on Dostoevsky

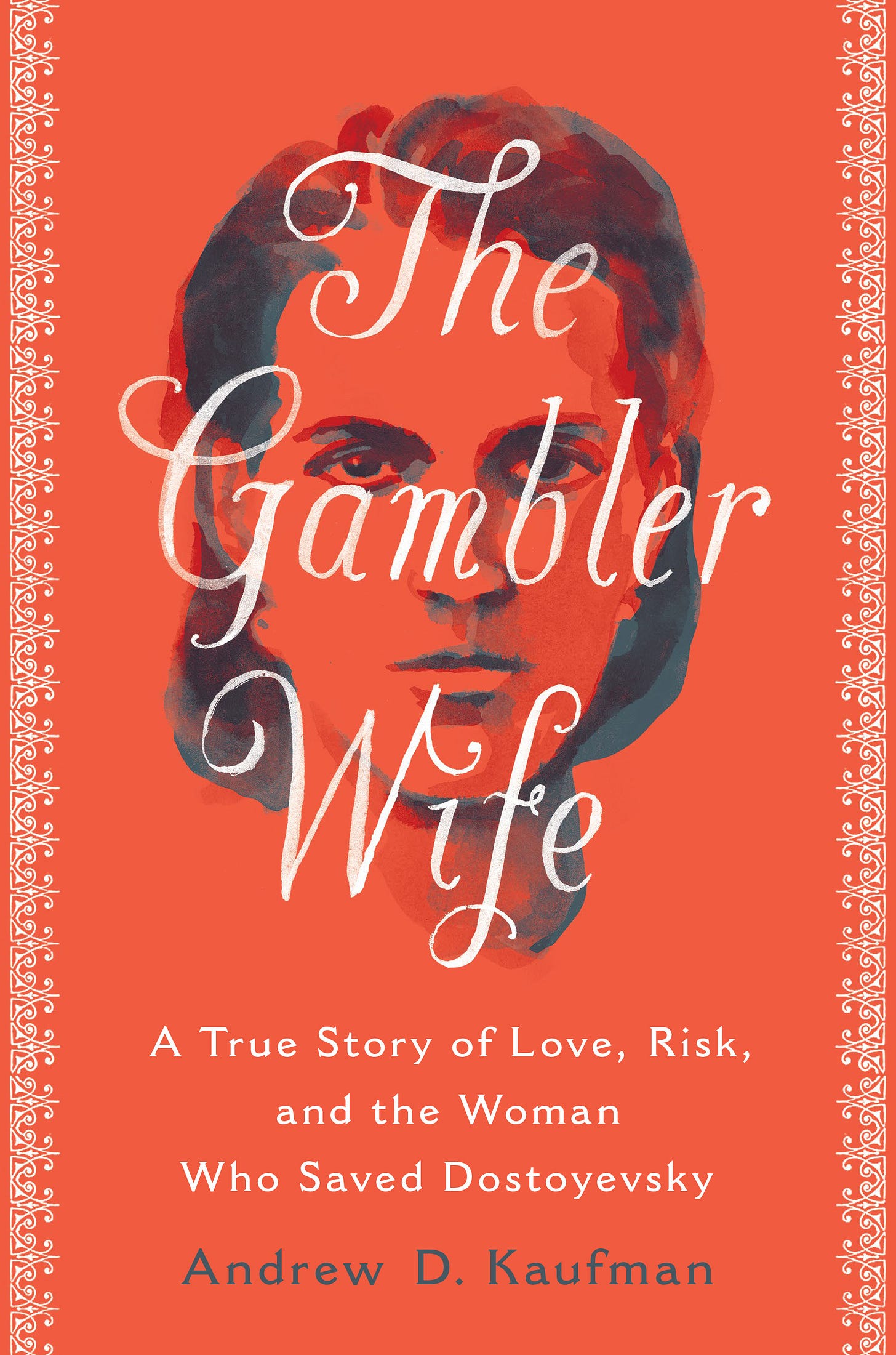

The Novelist’s Life and Business Partner. Reviewing ‘The Gambler Wife’ by Andrew D. Kaufman

In September 1875, Fyodor Dostoevsky, his wife Anna, and their three children, including a one-month-old baby, traveled to St. Petersburg. The luggage contained the final installment of his new novel, The Adolescent, along with all his notebooks for the complete project. Desperately needed money awaited his publisher’s reception.

After disembarking from a ferry, the family took a coach to the train station for the final leg of the journey. But when Anna went to retrieve her husband’s treasure-laden trunk, it was missing!

What to do? In a flash, Anna determined it must have been left at the dock. Night was falling, and the neighborhood was rough with hoodlums lurking about. No matter: She bolted to the road and hired a cab to whisk her back to the ferry.

When she arrived, she pounded on an office window. “Guard,” she shouted, “open up—open up right this minute!” It took a moment for the groggy man to respond, but, to Anna’s relief, he had the trunk.

Unhelpfully, the guard refused to haul it to the cab. The cabbie refused as well, worried someone might steal his rig if he stepped down from his seat. Oh, well. Anna dragged it to the cab herself and sat atop her spoils the whole ride back to the train station.

Dostoevsky met her at the station, flustered. Where had she gone? What was she thinking? “Anya,” he said. “Your rashness will lead you to no good!” After eight years of marriage, you might think he would have known better.

What Dostoevsky considered rashness was actually Anna’s well-calibrated intuition—intuition that, when paired with intelligence and diligence, made her Russia’s most notable nineteenth-century female entrepreneur and the only reason Dostoevsky’s career amounted to anything. What’s more, she’s probably the only reason people read Dostoevsky today.

However, as Andrew Kaufman shows in his biography of Anna Dostoevskaya, The Gambler Wife, their relationship didn’t start out so promising.

An Unlikely Marriage

Anna Grigoryevna Snitkina didn’t much like the novelist at their first encounter. Their relationship began long before they ever met, through his early fiction. Anna’s father read and admired Dostoevsky. So did she—so much, in fact, she garnered a family nickname from one of his unfinished novels. But meeting him in person was another matter.

Anna came from a loving and devout Orthodox Christian household, though she was somewhat progressive for the time. She pursued a career in stenography to look after her own needs and eagerly took a job to help Dostoevsky with a rush project, a short novel called The Gambler. But Dostoevsky was nervy and dour. “He made me feel depressed,” she said.

Still, the pair stuck it out and delivered the rush manuscript on time. Importantly, they kept working together thereafter. In The Sinner and the Saint (reviewed here) Kevin Birmingham tells the Dostoevsky story up to the completion of Crime and Punishment with Anna’s help as his stenographer. But there is no Dostoevsky story after Crime and Punishment that doesn’t involve Anna—as stenographer and also as wife, enabler, business partner, publisher, manager, and more.

In many ways Kaufman’s biography of Anna is the second half of Birmingham’s tale, picking up almost exactly where the other left off. But now with room for her own story, Anna comes into her own.

Anna’s initial impression softened, and she came to find her famous client interesting, even captivating, enough so that when he offered a sheepish and somewhat strained marriage proposal, Anna actually agreed—despite the fact that he was forty-five, she just twenty.

Anna had no idea what she was getting herself into. Not only was Dostoevsky given to debilitating epileptic fits, he had a mountain of debts and an impossibly difficult family who ate up whatever money he couldn’t first channel to his impatient creditors. He was in the habit of pawning everything of value—including his own winter coat.

Reality dropped with all its unhappy gravity immediately after the two were married.

Gambling in Exile

Anna could hardly believe how serious was her husband’s illness, needy and manipulative her in-laws, and grabby their creditors. The last were especially troubling. However backward debtors’ prison might strike us today, it stood as genuine threat to Anna’s newly-wedded bliss. So before long, the couple absconded to Germany for a three-month honeymoon that last four years.

Why so long? Dostoevsky had to write their way out of debt someplace where he wouldn’t get jailed before he was finished or his family chiseled away the gains. But the unseen hitch was own disastrous penchant for roulette, which he believed would save them financially.

If he followed a strict system of staying cool and riding out the losses, he believed he’d eventually win big. And sometimes he did—before losing it all. Time and again he lost everything they’d accumulated. Once he came home triumphantly with a bag of gold. It was all gone again in hours. He could never quit when he was ahead.

The couple was forced to pawn their valuables—and then pretty much everything else. Dostoevsky pawned Anna’s wedding ring, reclaimed it, and lost it again. At one point Anna was reduced to pawning her underwear. They were able to secure some loans, but Dostoevsky squandered most of those funds as well.

As their situation worsened, writing was the only answer. Perversely, their dire straits provided a crucible for his creativity.

Dostoevsky’s work has long been criticized for its hurried and chaotic style. It’s directly attributable to writing under brutal deadlines after squandering more leisurely options. The pressure formed the only conditions in which he could sit down and write. Anna actually put this to her advantage from time to time, sending her antsy husband to the roulette tables knowing he’d be able to finally focus when he was finished.

She tried the wheel herself once, earning her the sobriquet Kaufman entitled her story. But her gamble was bigger than mere roulette. Anna eventually took control of the family purse, a first step toward becoming Dostoevsky’s business manager. She gambled on her husband, on his talent, and her own resilience amid the tumultuous ups and downs of those early years—including the death of their first child.

In Business for Herself

The pair craved Russia and in 1871 were finally willing to face the risks of return. Once back, Anna triaged their debts, negotiated with creditors, and fended off the wolves.

“Troubles don’t come singly,” runs a Russian proverb. Anna quoted the line in her journal during this period, commenting: “That is when you see that a merciful God in sending us ordeals grants us the strength to endure them!”

Thankfully, Dostoevsky had finally shaken his gambling bug. Now the pair just needed one of his novels to hit big—a gamble all its own. He’d been working on a new project, The Possessed, before leaving Germany. Published serially between 1871 and 1872, the book was a massive success.

Anna realized Dostoevsky could rely on literary journals to publish his novels in their initial installments but then self-publish the final book themselves. She began researching the trade, visiting bookshops and making inquiries. She eventually worked out the entire business model: typesetting, paper buying, printing, binding, selling, and the rest.

The couple had lived book advance to book advance. Anna finally figured how to leapfrog the old cycle and surge ahead financially. Dostoevsky went along with the venture but doubted it would amount to much; perhaps he didn’t want to hold out hope.

An ad for Anna’s exclusive edition of The Possessed hit a St. Petersburg newspaper the morning of January 22, 1873. Bookshops responded immediately, ordering copies for their clientele. When they tried negotiating her discount, Anna confidently held her ground. She even turned away a buyer who nonetheless consented later that same morning; if his competitors had the book, he certainly needed it too—even on Anna’s terms.

When Dostoevsky finally emerged from his room several hours later, Anna was eager to share the news. “Well, Anyechka, how’s our business going?” he asked. He figured she might have sold a single copy. But no. By then she’d sold well over a hundred! He realized she wasn’t joking when she pulled three hundred rubles from her pocket.

It was a promise of things to come. Anna—“Russia’s first solo woman publisher,” as Kaufman says—successfully published Dostoevsky’s future novels, The Adolescent and The Brothers Karamazov, along with the rest of his back catalog. The couple also launched a periodical that garnered over seven thousand subscribers at its height. Beyond those ventures, Anna started a book service, distributing books to the hinterlands.

She settled with hungry creditors and created financial security for their family for the first time ever. “For Dostoyevsky,” writes Kaufman,

the psychological benefits of Annas publishing success were every bit as important as the financial rewards. At last he was able to free himself from the humiliating ranks of what he considered the ‘literary proletariat,’ ending his subservience to the whims of powerful editors and publishers to seize the kind of independence experienced by wealthier aristocratic contemporaries. . . .

Anna’s Enduring Legacy

Anna’s business acumen only sharpened over time, rarely failing her. After emphysema claimed Dostoevsky’s life in 1881 she issued several editions of his collected works. She compiled a massive bibliographic index of his work. She funded a museum. All of this secured fame and attention outstripping any he experienced in life.

Along with those efforts, Anna sent free copies of his work to libraries and used her own money to open new libraries. She also started a school and helped secure funding for its operation, ensuring that girls would receive equal education to boys; by 1917, the school had graduated over a thousand girls. In 1911, she sold the copyrights to her husband’s work for 150,000 rubles and plowed the funds into more legacy building.

Anna lived into the Russian Revolution, dying in June 1918. Her legacy persists to this day in the ongoing interest and enthusiasm shared for Dostoevsky’s work. Without Anna’s influence and management of her husband’s creative output, he would have little legacy of his own—certainly nothing with the reach he attained. She binds every page.

Says Kaufman,

Not only had she made Dostoyevsky’s creations possible; in a way, Anna was the ideal behind his creations. She was the living embodiment of the principles of Russian courage, moral integrity, and active love that had become central to his worldview. . . .

What’s more, as Kaufman shows, she forged a path of her own, betting everything on her artist husband and her own hard-won abilities to manage his career and secure his name. “In so doing,” he says, “she created a model of female agency that still has the power to inspire those of us—women and men alike—who seek meaning and fulfillment in our own troubled times.”

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Combine Anna Dostoevskaya’s story with the backstory of Crime and Punishment and a review of the latest Brothers Karamazov translation.

Fascinating post and perfect timing as we will be visiting the Kunstmuseum Basel this afternoon where Dostoevsky had a near seizure in 1867 as related in Anna's memoirs:

“On our way to Geneva, we stopped for a day in Basel to see a painting in the museum there that my husband had heard about. This painting by Hans Holbein depicts Christ who has endured inhuman torment, already taken down from the cross and decaying. His bloated face is covered with bloody wounds and his appearance is terrible. The painting had a crushing impact on Fyodor Mikhailovich. He stood before it as if stunned. And I did not have the strength to look at it – it was too painful for me, particularly in my sickly [pregnant] condition – and I went into the other rooms. When I came back after fifteen or twenty minutes, I found him still riveted to the same spot in front of the painting. His agitated face had a kind of dread in it, something I had noticed more than once during the first moments of an epileptic seizure. Quietly I took my husband by the arm, led him into another room and sat him down on a bench, expecting the attack from one minute to the next. Luckily this did not happen. He calmed down little by little and left the museum, but insisted on returning once again to view this painting which had struck him so powerfully.”

What a fascinating account! The people (often women) behind great writers are a subject worthy of study