Purple Rage? A Book to Offend Almost Everyone

Both Beloved and Banned: Reviewing Alice Walker’s ‘The Color Purple’

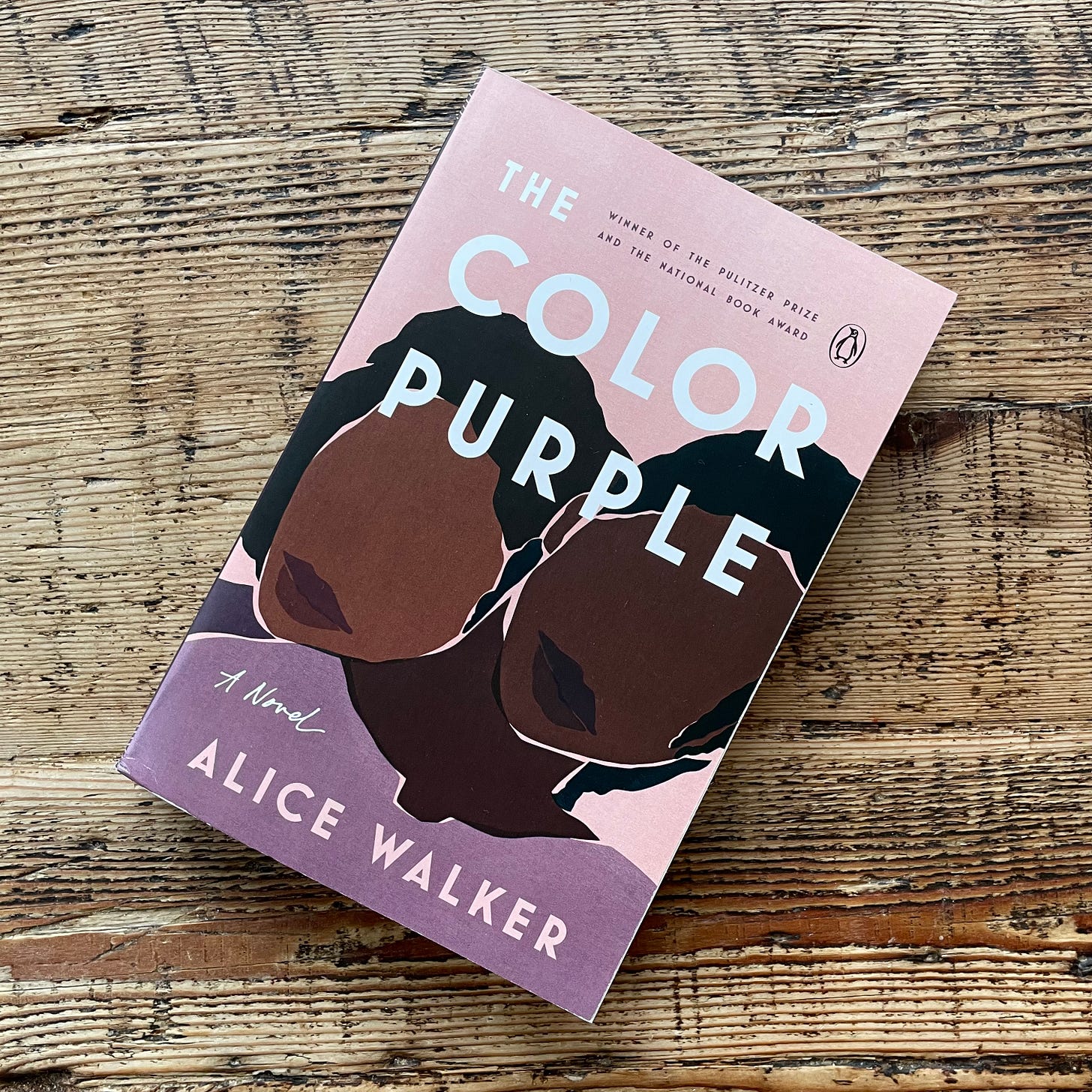

If you’re interested in book banning, take note of 1982. The year witnessed not only the inaugural Banned Books Week but also the Supreme Court ruling in Island Trees v. Pico, in which the high court sided with students who sued their school district for removing books from their library. Then, as if to provide an ideal case study, 1982 further saw the publication of Alice Walker’s The Color Purple, a book which won Walker the Pulitzer Prize, National Book Award, and status as one of America’s most banned authors.

Over the last thirty-odd years, the America Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom has compiled a list of the most-banned books by decade. The Color Purple charts on every list: 1990–1999, 2000–2009, and 2010–2019. The banning began in 1984 (ironically enough) when an Oakland, California, parent petitioned her tenth-grader’s school to remove the book as “garbage.” While the Oakland school board eventually relented and reinstated the book, The Color Purple has been targeted all over the country pretty much every year since.

Why? Complaints include everything from Walker’s dialect-infused narration to explicit language, drug use, sex—including sexual abuse and a same-sex relationship—physical abuse, and anti-religious sentiment. In the middle eighties the primary gripe actually came from African American men complaining that Walker’s depiction of domestic violence painted black males as dangerous aggressors—a claim that intensified following Steven Spielberg’s 1986 movie adaptation. Walker, it turned out, had something to offend almost everyone.

Of course, the book also won those coveted prizes and has also sold over five million copies, so it has its fans—often citing the same features that soured others. Oprah Winfrey, who acted in the movie, deeply identified with the book. “I opened the page and saw Dear God, fourteen years old, what's happening to me? Being a girl who at fourteen years old who had a baby, I was like, ‘There’s another human being with my story,’” she told Pulitzer-winning critic Salamishah Tillet. As an adolescent Oprah had been raped several times by male relatives and family friends—all of it hushed up and ignored, including the death of her premature baby.

Oprah discovered the book through a New York Times review while living in Baltimore, Maryland. Still in her pajamas, she left the house to purchase a copy from a nearby bookstore and read it in a single sitting. She then bought up every copy she could find and began handing them out to everyone she knew. It was, said Oprah, “the single most defining experience I’ve ever had. It opened me up in ways I didn’t even know.” Without stumbling onto that review, she said, “My life would have gone a completely different direction. . . .”

Tillet closely identifies with the book as well and for similar reasons. She first read the book at fifteen, but it took on new dimensions after she was raped as a college freshman and sexually assaulted during a study-abroad program. Walker’s story helped define Tillet’s trauma and encouraged her to become vocal about it. “I broke my silence because of The Color Purple,” she says in her exploration of the novel, In Search of The Color Purple. Now as a college professor, Tillet teaches the novel that enabled her recovery.

What’s in this story that moves people both for and against? Walker set her tale in rural Georgia in the decades between World War I and II. The narrative moves through a series of letters, first from the heroine Celie to God, unburdening her mind and heart about her life, beginning at fourteen years old with rape at the hands of her stepfather. Told to keep quiet, the young girl never betrays him, though she finds herself with child twice; her stepfather takes the children away—she assumes to kill them.

Eventually the man tires of Celie and marries her off to another. He goes by Albert, but Celie simply refers to him as “Mr. _____” in her letters. Similarly abusive, Albert beats Celie to keep her in line. What’s more, he invites his mistress, blues singer Shug Avery, to stay in their home. And, worst of all, he hides letters sent from Celie’s little sister Nettie, who attaches herself to a missionary couple en route to Africa and knows the true fate of Celie’s two children.

Exploited by men, perhaps it’s little surprise Celie feels no affection for them. The surprise? She forms a friendship with her husband’s mistress that eventually turns romantic. Shug still carries on with Albert and, after she leaves and marries a man named Grady, continues her relationship with Celie. In time she convinces Celie to leave Albert over his betrayal with the letters and come with her to Memphis to start a tailoring business.

Through these ordeals, Celie stops writing God, convinced he’s done nothing for her. But her tragic life does turn for the good. With Shug and Celie gone, Albert softens and even reforms; when years later Celie returns to inherit property stolen by her now-deceased stepfather, she finds herself able to befriend him. And it’s there she’s finally reunited with her sister Nettie and her two lost children.

It’s a brutal tale, and one that perhaps hits more panic buttons for readers than others. But need it? Take the claim about the book’s anti-religious message. Walker refers to herself as a “born-again pagan” and presents Celie’s early letters in the book as a sort of failed theodicy. But Nettie remains a faithful believer, is married to a missionary, and emerges as one of the book’s many uplifting features. What Celie explicitly denies is the idea that God is a disappointing, barefooted, graybearded white man in a robe. I suppose people could take offense at that, but why?

There is, of course, the violence and the sex. Though it’s essential to the story, it’s not gratuitous. It is provocative, intentionally so. Domestic abuse is real and rightfully disturbing when depicted. That’s the point. Should teenagers be required to think about such things? Perhaps not. Parents and school boards—and unfortunately, increasingly, depressingly, legislatures and courts—can decide that. But we’re fooling ourselves if we think we can shelter students from such realities when they already either live those experiences or sit two desks over from someone who does.

In the hands of a discerning student or thoughtful teacher such a book can, as happened for Oprah and Tillet, help make sense of suffering. Does that mean students must simply imbibe and adopt Walker’s answers to these problems? No. That’s what thinking is for. Books assist thinking; they don’t do it for us. Or have we forgotten that?

The Color Purple is book No. 2 in my classic novel goal for 2024:

January: F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

February: Alice Walker, The Color Purple

March: Thornton Wilder, The Bridge of San Luis Rey

April: Gwendolyn Brooks, Maud Martha

May: Chuang Hua, Crossings

June: Willa Cather, My Àntonia

July: Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse-Five

August: Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, A Grain of Wheat

September: Robert Penn Warren, All the King’s Men

October: Ray Bradbury, Something Wicked This Way Comes

November: George Eliot, Middlemarch

December: Ernest J. Gaines, A Lesson Before Dying

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Related posts:

I don't know if I have the courage to read it, but I understand the need for it to be written. As for the question of whether it should be read in schools, the vast majority of adolescents in history have had to grow up much faster than modern Western teens. My great grandmother was hired out as a domestic servant by age twelve. Twelve or thirteen was the age working class children entered servitude or were indentured as apprentices, which meant living away from home and working all day for six and a half days a week. They saw plenty of the grit of life. My great grandmother's friend and later sister-in-law, also a teen in domestic service, became pregnant out of wedlock, twice - we do not know who the fathers were but we do know her mother defended her when her father shunned her. The post-war Western cultural development of a leisurely and sheltered adolescence is a temporary and isolated socio-economic phenomena in the long history of the world.

"Banned" books are not actually banned, just for the record. Any book anyone chooses to read can be easily and cheaply found in public libraries, bookstores, Amazon, etc. I mention this only because it was brought up as part of the review and the discussion of the book.

When people argue that a book should be made available to children in school they aren't arguing that the book should be available to THEIR children (because they can easily acquire the book for their own child to read), they are arguing that the book should be made available to MY child and YOUR child.

I agree that these decisions should be made at the local level because they know and are answerable to the local population and parents.