Thinking Is a Group Sport

A Guide to Clear Thinking in a Confusing World: Alan Jacobs’s ‘How to Think’

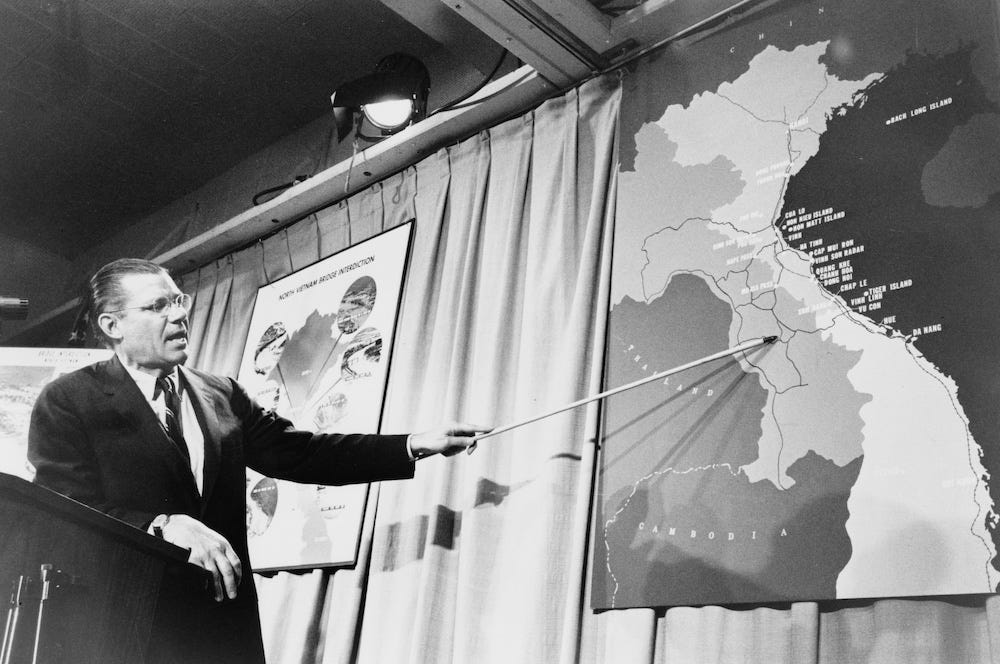

During the early days of the Vietnam War, U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara wanted to know if American military efforts were effective. He charted the numbers of weapons lost, enemies killed, and so on. McNamara’s accounting was exhaustive and exacting, but he overlooked something.

A critical colleague told McNamara he’d failed to count “the feelings of the Vietnamese people.” It proved a fatal miss. While experts in Saigon and Washington insisted America would win the war in no time, alienating the South Vietnamese spoiled any chance of American victory.

It’s easy to spot the failures at this distance, but the truth is we’re all prone to similar miscalculations and oversights—though usually less disastrous. “We are good,” as philosopher Karl Popper said, “but we are also a little stupid; and it is this mixture of goodness and stupidity which lies at the root of our troubles.”

Smart people think, say, and do stupid stuff all the time. One explanation? We’re sometimes more intelligent than critical. Researchers who’ve studied the phenomenon of intelligent people making stupid decisions note that critical thinkers experience fewer negative events in life, even when compared to highly intelligent people, because their critical lens helps them avoid mistakes the rest of us blindly stumble into.

The good news, researchers say, is we can all learn how to think more critically. But to do so takes more than just thinking. It requires thinking about our thinking. And for that there are few guides better than Baylor professor Alan Jacobs’s book How to Think: A Survival Guide for a World at Odds.

A Process, Not a Product

We often mistake thought for a product. After all, it’s what our brain produces. But thought is really a process. Since we usually focus on what—and not how—we think, we’re liable to goof. Thankfully, Jacobs illumines our path.

He starts by explaining most of our thinking isn’t really thinking. It’s more like mental shortcutting. If we had to dissect the world at every turn, we’d never get anywhere. We all develop habits of mind that help us compress and even sidestep most of the thinking we might otherwise have to do (which is good news because we’ve got mortgages to pay). The problem is that some of that shortcutting fails us, and we fall for traps set by our own false assumptions or hasty conclusions.

There’s an entire literature on biases, heuristics, and fallacies that lead individual thinkers astray. But that literature mostly overlooks something essential for how individuals think: It’s a mistake to think we do it alone.

Yes, we cook up some of these shortcuts on our own. But plenty—probably most—are given to us by others. We never think in a vacuum. “Thinking is necessarily, thoroughly, and wonderfully social,” says Jacobs. “Everything you think is a response to what someone else has thought and said.”

But it goes well beyond reaction. Jacobs’s deeper point concerns formation. Our thinking is heavily influenced by our social circles: “To dwell habitually with people is inevitably to adopt their ways of approaching the world.”

Ideas and assumptions circulate in our various communities. To save the time and trouble of deliberative thought, we pick up these prefab notions. Such shortcuts are necessary but necessarily fraught. Consider what can go wrong when a single hashtag substitutes for an entire train of thought.

Our People, Other People

Hashtags exemplify what Jacobs calls “keywords,” by which he means terms any given community takes for granted. If you’re in the group, you know what they mean (more or less) and use them accordingly. Political conversations and business writing, as two examples, are full of keywords.

The problem is that keywords often replace actual, deliberative thinking. “They will construct your sentences for you—even think your thoughts for you, to a certain extent,” Jacobs quotes George Orwell as saying. “They will perform the important service of partially concealing your meaning even from yourself.” The truth of those words can be easily seen in the last contentious Twitter exchange you read.

If we’re not critical enough in our thinking to recognize how the process works, we default to unhelpful attitudes, ideas, and practices. They’re like an autopilot system steering us toward some truths, while skirting others. Occasionally, they send us into a ditch.

“We come to rely on keywords, and then metaphors, and then myths,” says Jacobs, “and at every stage habits become more deeply ingrained in us, habits that inhibit our ability to think.” The more invested we are in our myths, the less likely we are to change our minds or value those who hold differing views.

Our allegiances play into other thought traps, as well, including:

in-other-wordsing (when we recast someone’s claims in distorting or dismissive language) or

lumping (when we collapse disparate people or ideas under one header for easy management).

We’re most susceptible to these traps when we—consciously or not—position ourselves and ideas against those people and their ideas, which we usually assume we understand far better than they do.

Avoiding the Traps

Once we see how and why we fall for various thought traps, we have choices to make. Though Jacobs starts the book by saying “diagnosis is the treatment” and summarizes key points in a “Thinking Person’s Checklist,” mere awareness is not enough.

Nor is it sufficient to simply decide to think for ourselves, which Jacobs argues is impossible. Thinking is, after all, a group sport. If thought is a process, and that process is substantially affected by the people we allow to influence our lives, then part of the answer lies in becoming more critical of how we think with others and who those others are.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

AI is not going to enhance deliberative thinking.

I read this book a few years ago and have thought of it many times since. It is clear and insightful. I hope more people read it!