3 Ways to Make New Stuff Happen

Lessons in Innovation from Buckminster Fuller, Martin Luther King Jr., Milton Friedman, and Sonny Rollins

One of the fascinating experiences afforded by reading biographies comes when noticing similarities between the lives of wildly disparate people. Think geodesic domes, protest marches, supply-demand charts, and saxophone solos in smoky New York nightclubs: Buckminster Fuller, Martin Luther King Jr., Milton Friedman, and Sonny Rollins wouldn’t seem to share many commonalities on the surface. But they’re more alike than you might imagine.

All four were innovators in their respective fields, and their life stories contain remarkably similar chapters, evident in several recent biographies:

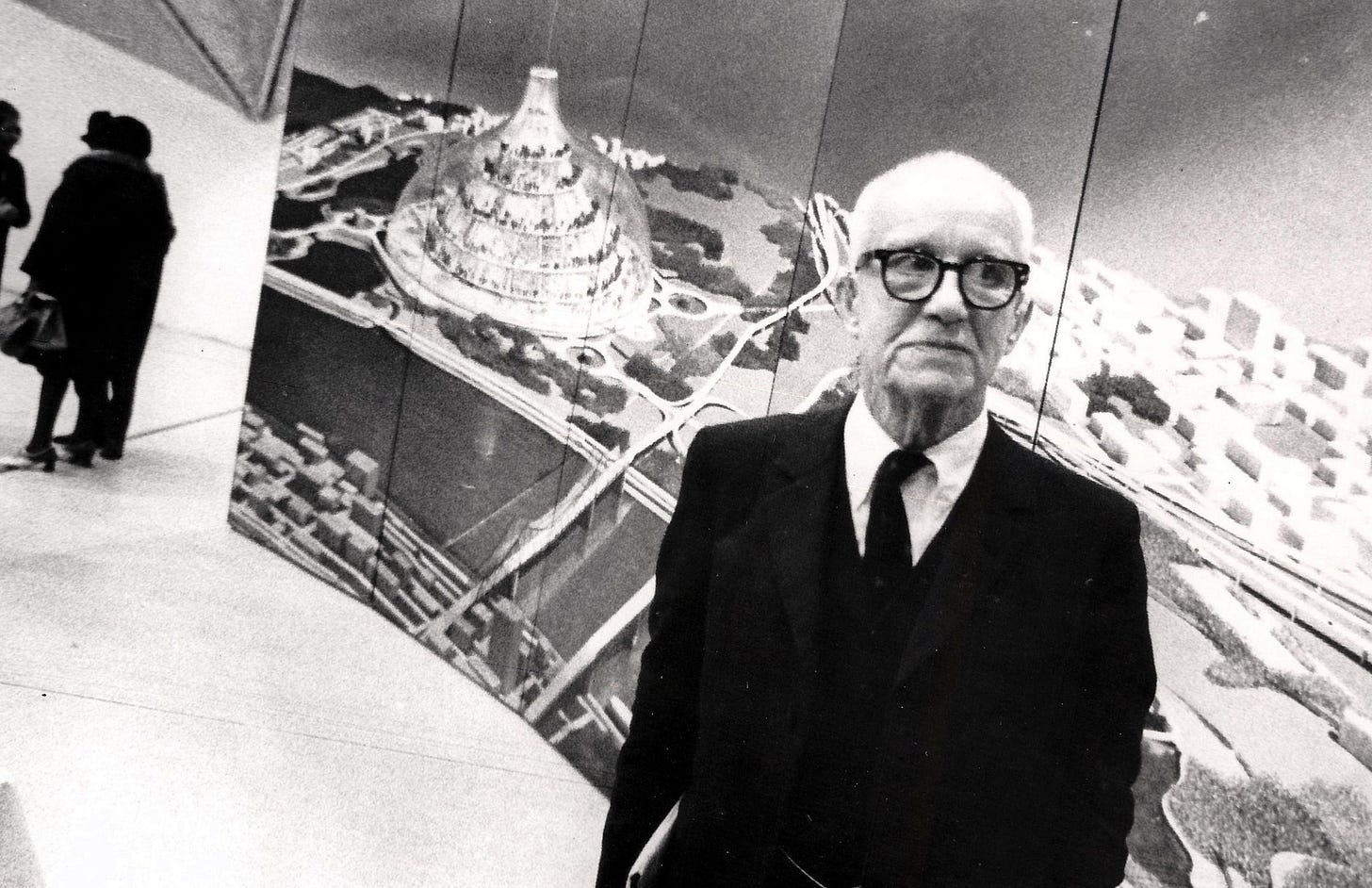

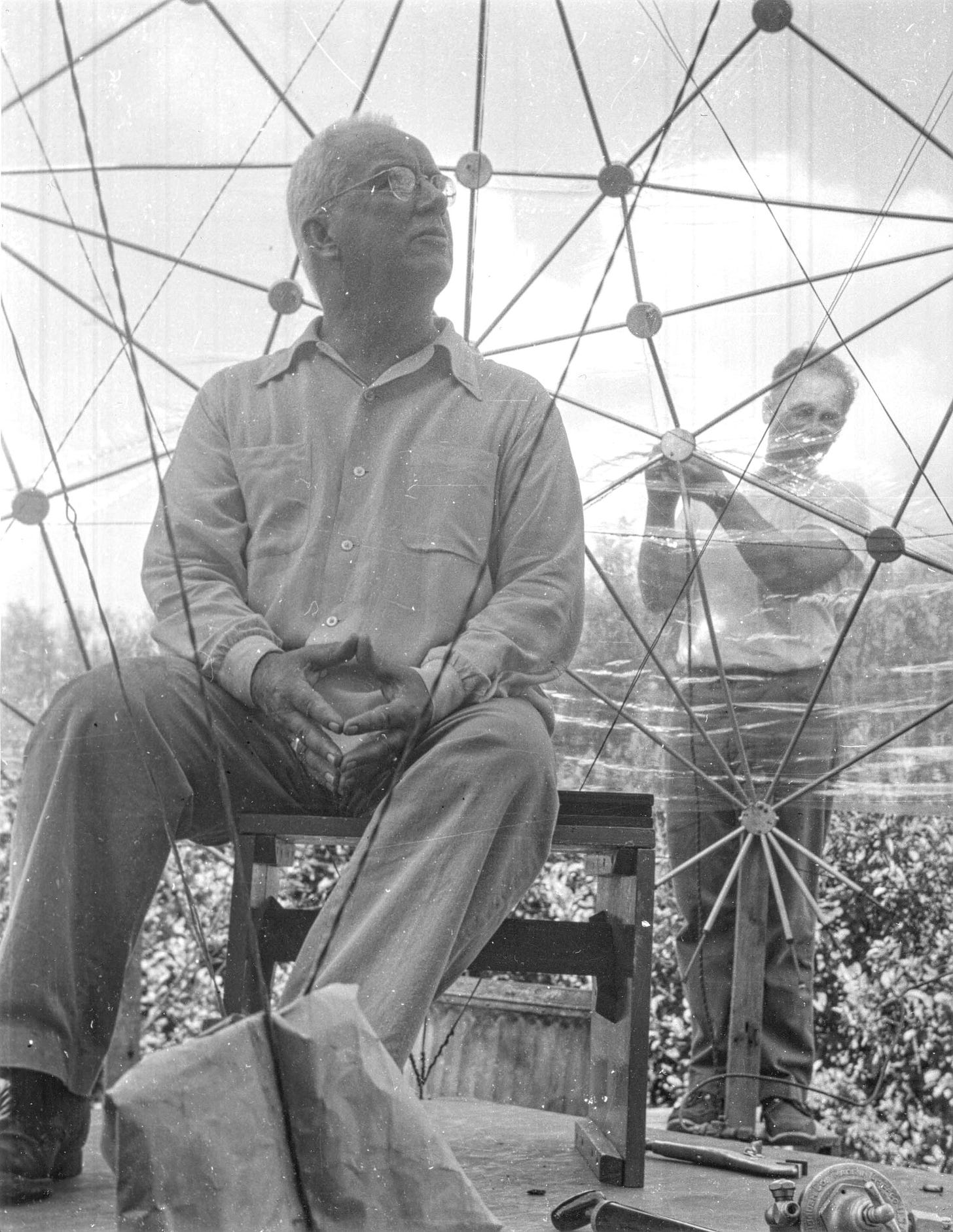

Inventor of the Future: The Visionary Life of Buckminster Fuller by Alec Nevala-Lee (2022);

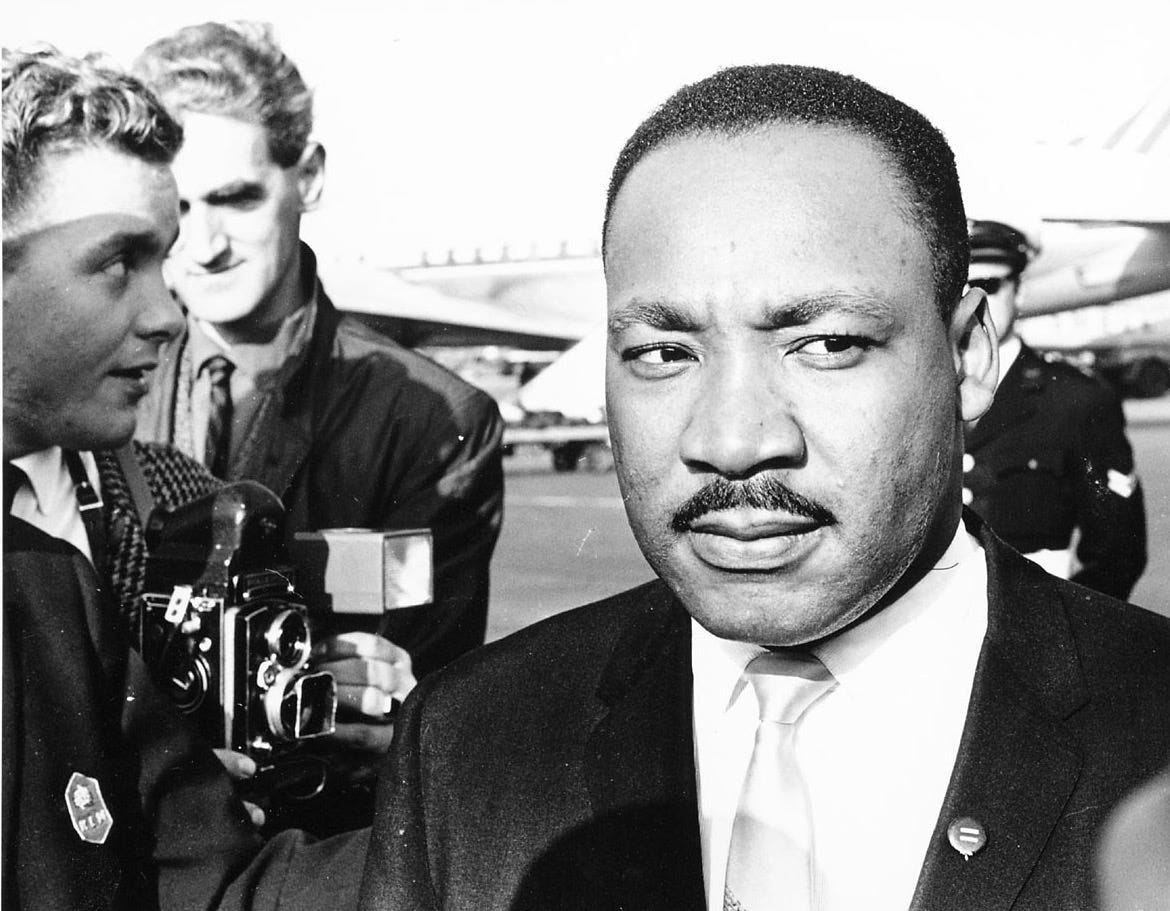

King: A Life by Jonathan Eig (2023), winner of the Pulitzer;

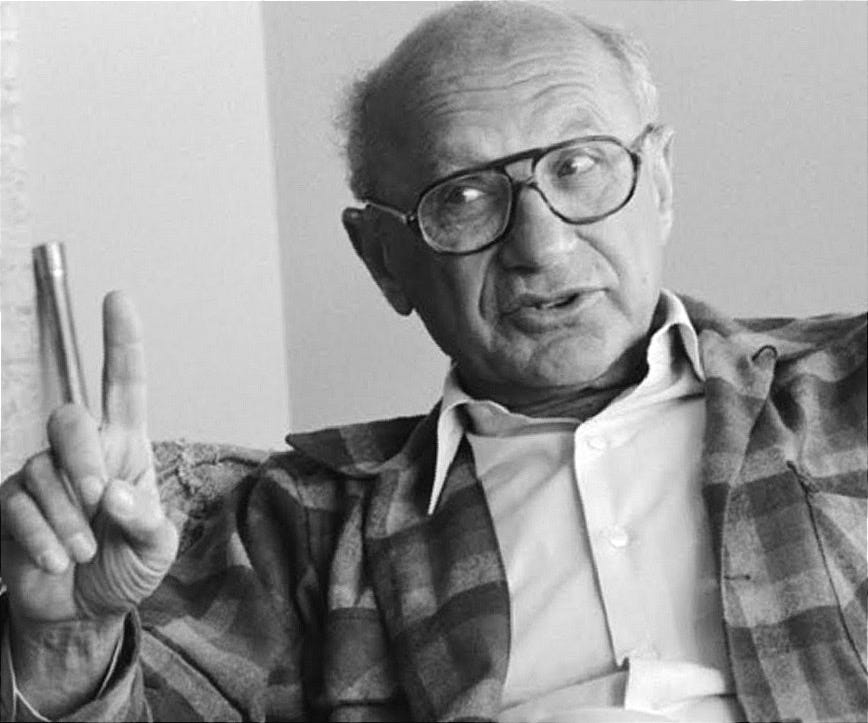

Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative by Jennifer Burns (2023);

Saxophone Colossus: The Life and Music of Sonny Rollins by Aidan Levy (2022), winner of the American Book Award.

Each story stands on its own, but what intrigues me are the overlaps and convergences. There are many, but I want to zero in on just three. They’re not so surprising the moment you frame their lives as innovators, but the patterns are pronounced and warrant deeper attention.

Beyond their common humanity, American citizenship, and (mostly) twentieth-century lifespans, what else do an architect and philosopher, preacher and activist, economist and policy wonk, and musician and composer share in common? If you’re looking to make new stuff happen, here’s how these four did it.

1. Develop an Irrepressible Vision

If you’ve been to Disney’s EPCOT or seen pictures of its gargantuan sphere, you know the influence of architect and philosopher Buckminster Fuller. Born in 1895, he thrived so far ahead of the curve he was always three steps ahead of the culture, the counterculture, and everyone else. He didn’t always make sense to those who tried to follow his trains of thought in lectures, demonstrations, and books, but he seemed to anticipate and advocate for a future that left even sci-fi novelists in the dust and the envious and anxious Soviet Union guessing what magic the Americans were up to.

Fuller—“Bucky” to intimates and enemies alike, not always fixed or mutually exclusive categories—imagined a comprehensive design language, a full-blown science, based in geometry that could unlock the secrets of the natural world and complex systems, allowing humans to optimize our resources and solve perplexing social and ecological problems. “My objective,” he said,

is to discover nature’s principles governing universe and to employ those principles in designing tools, instruments and systems capable of anticipatorily solving the problems now threatening man and extinguishing all life aboard our Spaceship Earth.

Oh, is that all, Bucky?

The perplexing problem that seized hold of Martin Luther King Jr. was racism and the plight of his fellow black Americans. Born in 1929, the Christian minister and civil-rights leader saw racism as a cancer in American society and wished to eradicate it. King advocated tirelessly for what he called the Beloved Community—a vision marked by societal justice, equality, and harmony for all people. “Now,” he said,

is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood.

King enrolled untold millions of Americans in this dream, though not without substantial conflict. Through it all, he stayed committed to nonviolence, recognizing that aggressive means would undermine his peaceful ends.

Economist Milton Friedman was possessed by a commitment to individual freedom and the concomitant need for free markets and limited government. Born in 1912, Friedman lived through the Great Depression and witnessed how New Deal government growth and intervention not only worsened the Depression’s societal impact but undermined individual freedom as well.

As an advocate for public policy grounded in this vision, he looked for ways to reduce the presence of government in individual lives and expand personal choice. On the one hand, he opposed tariffs, wage-and-price controls, and other forms of economic regulation and, on the other, promoted:

School choice, specifically vouchers;

an all-volunteer army, ending conscription;

direct cash payments to low-income individuals—as a simplification of complex welfare programs;

drug legalization, ending police interference in citizens’ lives;

controlling inflation through simple monetary rules, rather than legislative programs; and

floating exchange rates, which allow national currencies to compete on the open market.

These and other initiatives reflected Friedman’s preference for the outcomes of individual choice and free markets over those of government intervention.

While these first three men—Fuller, King, and Friedman—were occupying a growing share of the popular discourse, saxophone virtuoso Sonny Rollins was staging a revolution of his own. Born a year after King, he’s the youngest of the group. Though he lived through decades of dehumanizing discrimination, his jazz compositions and improvisations embodied the same sort of self-determination, freedom, and dynamism championed by Fuller, King, and Friedman.

Like all true originals, Rollins began by copying everyone who had come before. He mastered his instrument, the language and style of bebop jazz, the vast American songbook, and more far-flung forms such as calypso. He distilled it all into a new vision of American music. “When I heard Sonny,” said fellow saxophonist Jimmy Heath, “that was startling, because his rhythmic concept was so strong. . . . His rhythmic concept, the way he put his lines together rhythmically, was attractive to everybody that heard it.” As Levy says in his biography, “Sonny was speaking the language his own way, not like Bird, Hawkins, Byas, or Pres, but a synthesis that was sui generis—like Sonny.”

Several threads composed Rollins’s unique vision for his art: perfectionism and a relentless push for personal growth and technical mastery, experimentation, unconventional arrangements, surprising melodies and winking musical quotation, spiritual sensitivity, self-determination, and (paradoxically) a willingness to embrace near total self-abnegation.

That meant Rollins—same as Fuller, King, and Friedman—encountered opposition from people at the center of their respective worlds, and they had to battle for influence and legitimacy from the periphery.

2. Embrace the Margins, Work Toward the Center

Despite a privileged upbringing, Fuller represents the perpetual outsider. Conventual design, architecture, technology, societal structures, even math: He consistently questioned it all, and plank after plank of his vision undermined them in one way or another. As a result, he was regarded as a crank by stakeholders in the disciplines he challenged. He found it hard to raise money, to keep an office, to retain his supporters—all of which was made harder by personal quirks and character defects (such as repeatedly taking credit for other people’s work).

Even some of his grandest ideas, including his advocacy of geodesic domes and housing inspired by grain silos, were based in part on his theories and his lack of financial resources. He emphasized “ephemeralization,” using fewer resources to build bigger, better structures based in his principle of tensegrity (his coinage for the idea that structural tensions can amplify structural integrity).

The idea worked in practice, which proved a gift because it was all he could afford. “Although he emphasized its structural efficiencies,” says biographer Nevala-Lee, “its first real benefit was that it could be prototyped for almost nothing, and its triangulated framework evoked the technology of tomorrow, as much for its aesthetic qualities as for its actual strengths.”

Coupled with his reputation for pushing boundaries and championing revolutionary ideas, Fuller pushed inward from the margin and won converts near the center. So did King.

King’s power stemmed from the fact that he represented a historically marginalized group denied their legitimate claim to human dignity, civil rights, political power, economic freedom, and social mobility. He was forced to work from the outside because that was the only position allotted to him by the entrenched white establishment. “The point of the movement,” said King, “was to take a crowbar and stick it into the cracks of the system.”

Nonviolence proved central to the strategy. When those in power began using force and coercion against people standing up for little more than the right to be heard, it engendered both sympathy for, and outrage on behalf of, the violated. Sit-ins and marches challenged the conscience of the country, especially when met by force; firehose and truncheon-wielding law enforcement might have possessed legal authority, but King and his movement possessed all the moral authority.

By working from the margins and maintaining the moral high ground, King built a coalition across racial lines that carried his demands to the center. Says biographer Eig,

King and the other leaders of the twentieth-century civil rights movement, along with millions of ordinary protesters, demanded that America live up to its stated ideals. They fought without muskets, without money, and without political power. They built their revolution on Christian love, on nonviolence, and on faith in humankind.

When Milton Friedman began his intellectual insurgency, he was completely on the outs. He possessed neither political power nor much academic support. Though he used the accepted tools of his trade, especially data and empirical research, he turned them against the prevailing view of his discipline, which advocated government management of the economy, tinkering with taxes and federal spending to smooth out bumps in the market, reduce inflation, increase employment, and avoid recessions (and worse).

Friedman thought all of that was rubbish. Instead of using tax-and-spend fiscal policy to fix the economy, he advocated for the outsider view of monetary policy. “Inflation is always and everywhere,” he said unceasingly, “a monetary phenomenon,” by which he meant a function of the total amount of money in the system. This, he thought, should be governed by a few simple rules, free of manipulation. In practice this dramatically reduced the power of the federal government, part of Friedman’s overall vision of a small state with limited interference in the lives of its citizens.

To advance his views, he found allies outside the traditional centers of influence, including the Mont Pelerin Society and later the Hoover Institution, and cultivated a public voice to communicate his views directly to the American people (more on that in a moment.)

Where Friedman leaned into public attention, Rollins leaned out—in more ways than one. First, his approach was unorthodox. He learned all the bebop basics but wanted to transcend its limits and structures. He experimented tonally, melodically, harmonically, rhythmically. Constantly looking for the right sound, he was rarely satisfied with his performances, especially those on his records. Critics didn’t quite know what to do with him, and his albums were sometimes savagely reviewed.

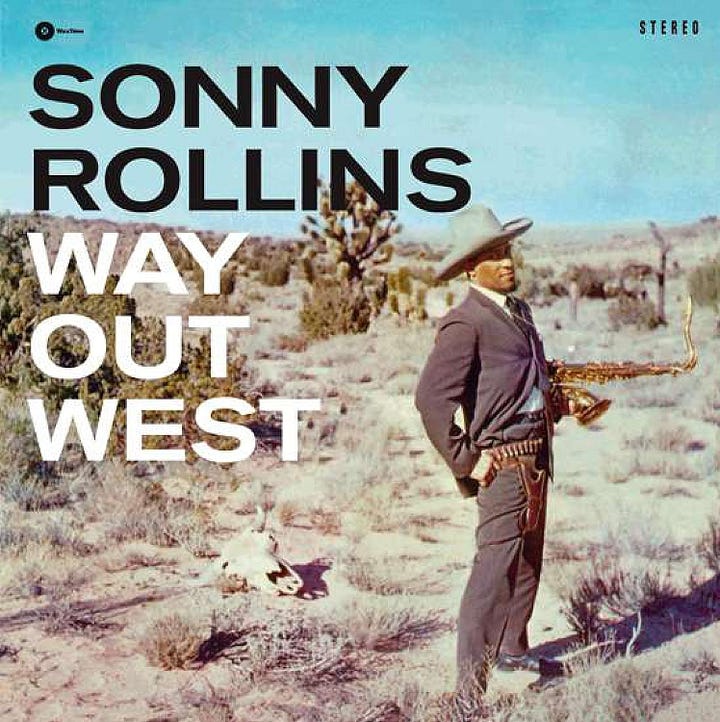

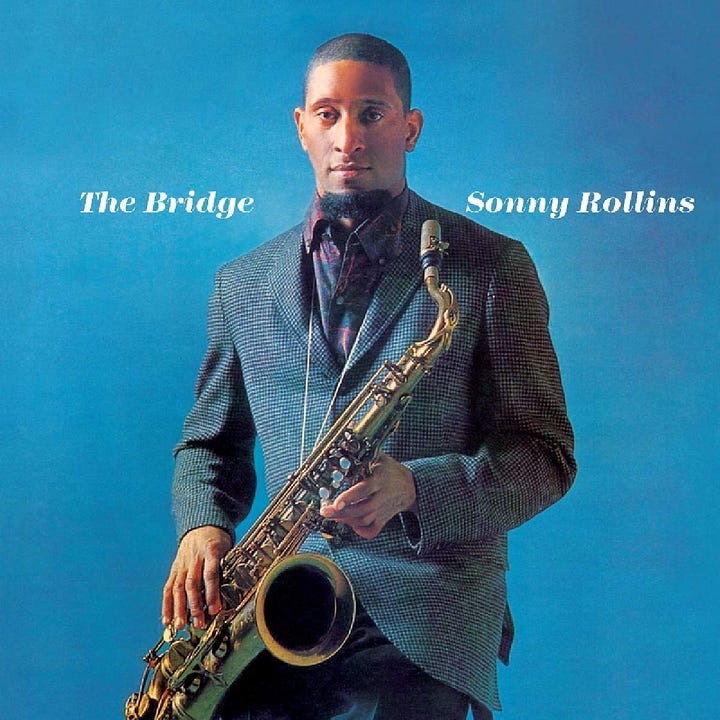

It never interfered with his innovating. A drummer, bassist, and pianist filled the usual seats in a standard jazz rhythm section. But what might happen if you dropped the piano? Rollins tried it and gave the world his first major hit, Way out West (1957). What if you left out the piano again but added a guitarist? The result was The Bridge (1962), which can still both enthrall and blast the hair off your head.

But while Rollins worked from the outside in, he always took solace and sustenance from the outside. Not only did he occasionally abandon public performance altogether, sneaking off for long periods of time to practice and develop something new, something fresh, he also launched his own record label and assumed near total creative control over his business. He might play to the center, but he would never let it swallow him.

For all four men, these outlandish bets paid off. While it cost them all, and in King’s case the ultimate price, they kept pushing for the realization of their respective visions and saw them come to fruition. But not without a final shared ingredient.

3. Sell the Vision Until It’s Sold

Fuller’s vision was so grandiose he would never see it fully embodied, but he dedicated himself to pushing it as far as he humanly could. He really never stopped inventing, patenting, writing, lecturing, modeling, and enrolling acolytes and students. On the lecture circuit, he was an awkward but spellbinding speaker, and in intimate settings he could sway nearly anyone.

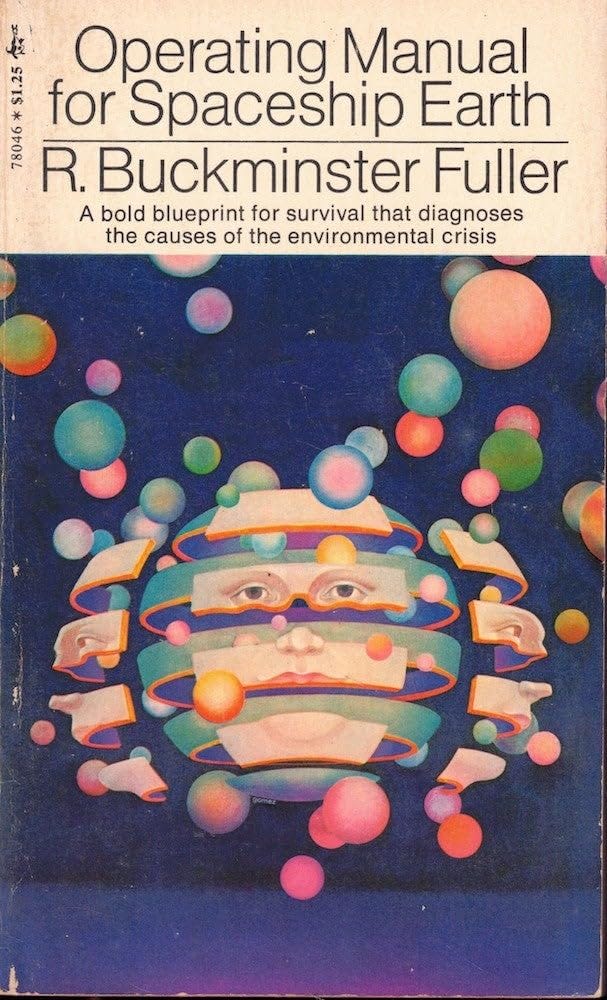

Books formed a core of his public outreach, communicating his complex vision and sometimes baffling point of view on the state of the world: Synergetics, Nine Chains to the Moon, Grunch of the Giants, Utopia or Oblivion, Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth, I Seem to Be a Verb, and others allowed both critical and mass engagement with his ideas. Some of these titles were even released as mass market paperbacks meant for a general audience.

King was no different in his relentless advocacy for his vision. Like Fuller, he published, but King’s special gifts were oratory and public protest. The March on Washington capped by his “I Have a Dream” speech galvanized the nation. No less important were the Selma-to-Montgomery marches, which elevated local voting rights to a national concern and helped set the stage for legislative reform.

Friedman was every bit as dedicated to selling his vision, using popular books like Capitalism and Freedom and Free to Choose, cowritten with his wife Rose, and other vehicles for mass influence. He secured a regular column in Newsweek, appeared frequently on television to debate and present—most famously in his hugely popular 1980 TV series Free to Choose. He also stayed engaged on the academic side of his work, lecturing and writing, developing and defending theories that still influence economists today.

And then there’s Sonny Rollins. He earned the nickname Saxophone Colossus early in his career and its significance only grew in the following decades. His recorded music, both studio albums and live in-the-moment performances, leave a crumb trail of his creative search, always hunting for the next expression. He was rarely satisfied because he never quite found it, but the critics eventually turned his way and audiences flocked to hear him.

In one way or another, we’re living in the world these four men shaped. Working from the margins, they refashioned the center.

The World They Built

People took from Fuller what they could—rarely the full package—but it was enough to create a lasting impact on the wider culture. His relentless push for innovation and alternative models for inventing, building, and thinking found eager adherents in the human potential movement and eventually Silicon Valley, where he was seen as a model for startup founders and a font of radical new ideas. Stewart Brand credited Fuller for his techno-optimistic influence on the Whole Earth Catalog, and Steve Jobs intentionally brought his limitless thinking into Apple. Fuller passed in 1983 at the age of 87.

Despite virulent opposition by state and local authorities, constant harassment from the FBI, and danger at every turn, King and the movement he led ultimately prevailed, not only in the form of legislation like the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, but most especially in the moral and cultural victory that has edged racism to the margins. King might have accomplished much more, but his life was cut short by an assassin on April 4, 1968. He was only 39.

Friedman’s views shaped economic and political discourse for decades, such that his vision was taken as normative in conservative circles and held significant sway on the center-left as well, only recently being challenged by the rejections of the MAGA movement on the right. He remains a revered figure among classical liberals, libertarians, and many conservatives. He died in 2006 at the age of 94.

Still living, though now retired and unable to play for health reasons, Rollins represents a towering figure in the history of jazz, improvisational music more broadly, and the saxophone in particular. Many of his compositions are now jazz standards and his name invokes both awe in his legions of fans and permission to experiment among musicians. Beyond that, his decision to handle his own tour-and-concert booking and record production foreshadowed the contemporary trend of artists controlling more and more aspects of their creative careers.

Incidentally, three of the four received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, King (posthumously) from Jimmy Carter in 1977, Fuller in 1983 from Ronald Reagan, and Friedman in 1988 by Reagan. And Barack Obama publicly praised Sonny Rollins during his reception of Kennedy Center honors.

But whatever their formal recognition, we live in the reality they helped to form. Their visions, their strategic action from the margins, and their persuasive communication have defined the world we all inhabit.

Now a question for you: Who is one innovator who think shaped our world?

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

I would say Steve Jobs is an important innovator. From making computers that anyone could use (Apple IICs) to powerful ones that used a GUI (Mac Classics) to upending the music industry (iPods and iTunes) to the smartphone. I'm not saying everything he introduced was beneficial, but practically every new Apple product created massive changes in education, business, entertainment, and personal habits.

Interesting multi stage schema. It would be interesting to see how many other innovators fit into it.